Using the Census

Census records are a valuable tool for the family historian. Do you know enough about them to use the effectively?

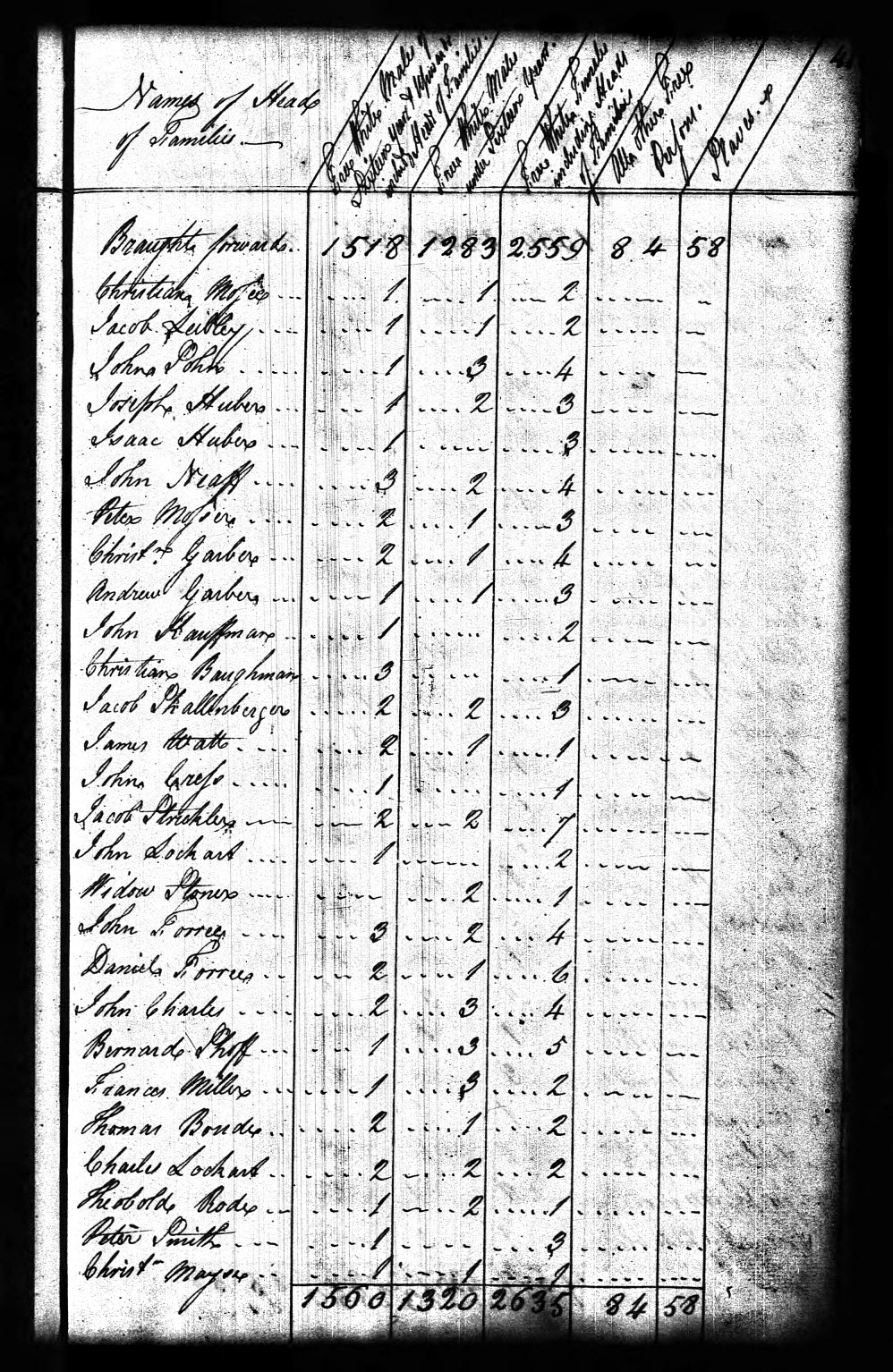

Initially there was no Census Bureau. From 1790 to 1870, the U.S. census was the responsibility of the federal marshals. Each marshal was to hire and manage the assistant federal marshals taking the census in his district. In many outlying areas it was a challenge to get to the inhabitants because of the terrain, lack of roads, lack of provisions and great distances.

Additionally, people were sometimes superstitious about the census. Before the 1790 census, one member of Congress remembered that “back in the 1770s most of the residents of a New York town had fallen sick right after they had been visited by a British census taker.”1 Another brought up the story from the bible where a plague visited Israel after King David ordered a census.

Census Day

Every census has a census day—the date the census enumeration was to represent. This date was not the day that the enumerator actually visited the household. The census taker was instructed to include all members of the household on the census day—even family members who had actually passed away between that date and the date the enumerator visited. Additionally, they were not to include any children born after that date, even if they were members of the household when the enumerator visited.

Knowing the date is important for estimating birth years. A person born before the date had already advanced a year in age from the previous year, but those born after the date would not have. Between 1790 and 1820, Congress set the census day for the first Monday in August. Between 1830 and 1900, the date was set as June 1st. In 1910, it was April 15th. It was January 1st for 1920 and April 1st for 1930. Depending on the census year, census takers were given between 1 month and 18 months to complete the enumeration for their district.

Both dates should probably be recorded. Although the census takers were given specific instructions, it’s impossible to know if they followed them.

Where Did They Live?

It’s also important to understand the changing borders between jurisdictions. Between census years new states, counties and even townships may have been added, changing border lines between jurisdictions. For instance, both Providence and Pequea townships were added to Lancaster County after 1850. A family in Conestoga Township in 1850 might appear in Pequea Township in 1860 without having changed their residence at all. A person living in Hardy County, Virginia in 1860 might have been living in Hardy County, West Virginia in 1870, again without having moved.

Lost

Just about everyone has heard of the destruction of the 1890 U.S. census, but do you know what other census records are lost or missing?

Until 1830, the census records were required to be deposited with the U.S. District Courts. The president was to receive only aggregate information about the people in each district. Congress enacted a law in 1830 calling for the records from the 1790-1820 censuses to be turned in to Washington. Some of the district court clerks did a better job than others of preserving those records. Some records were either lost before 1830 or were simply never sent to Washington. The following lists the lost records:

- Alabama: 1790-1810 not taken, 1820 lost

- Arkansas: 1790-1810 not taken, 1820 lost

- District of Columbia: 1790-1800 not taken, 1810 lost

- Delaware: 1790 lost

- Georgia: 1790-1810 lost; 1820 3 counties lost

- Illinois: 170 not taken, 1800 lost, 1810 St. Clair county lost

- Indiana: 1790 not taken, 1800-1810 lost

- Kentucky: 1790-1800 lost

- Louisiana: 1790-1800 not taken

- Maryland: 3 counties missing from 1790

- Michigan: 1790-1800 not taken, 1810 lost

- Mississippi: 1790 not taken, 1800-1810 lost

- Missouri: 1790-1800 not taken, 1810-1820 lost

- New Hampshire: 1790 missing 13 towns in Rockingham county & 11 towns in Strafford county

- New Jersey: 1790-1820 lost

- North Carolina: 1790 missing 3 counties, 1810 missing 4 counties, 1820 missing 6 counties

- Ohio: 1790-1800 not taken, 1810 lost

- Tennessee: 1790 not taken, 1800-1810 lost, 1820 20 eastern counties (Knoxville district) presumed lost

- Virginia: 1790-1800 lost (1790 compiled from 1785-1787 county tax lists)

Tips

- The 1820 census includes the category males “16-18.” Those in this column will also be in the “16-26” category. Check the total household number to ensure that they weren’t included twice.

- The microfilmed 1830-1840 federal census records may have been taken from copies incorrectly sent to Washington instead of the original. Check to see if the handwriting changed between one district and another to determine if it’s a copy or the original.

- Comparisons with original records for the 1850-1870—where they still exist—reveal that there were often errors made in copying the records. Names were misspelled or sometimes omitted, ages were copied incorrectly.

For more information about the census records or how to use them effectively, try one of these books:2

Footnotes

Cite This Page:

Kris Hocker, "Using the Census," A Pennsylvania Dutch Genealogy, the genealogy & family research site of Kris Hocker, modified 6 Aug 2011 (https://www.krishocker.com/using-the-census/ : accessed 26 Apr 2025).

Content copyright © 2011 Kris Hocker. Please do not copy without prior permission, attribution, and link back to this page.