Will: Conrad Schneider of Upper Salford, Translation

I’ve been researching the ancestry of Jacob Schneider for some time now. Just about every advance I’ve made has been through genetic genealogy research. That doesn’t mean I haven’t been working to find genealogical evidence—the so-called paper trail, too.

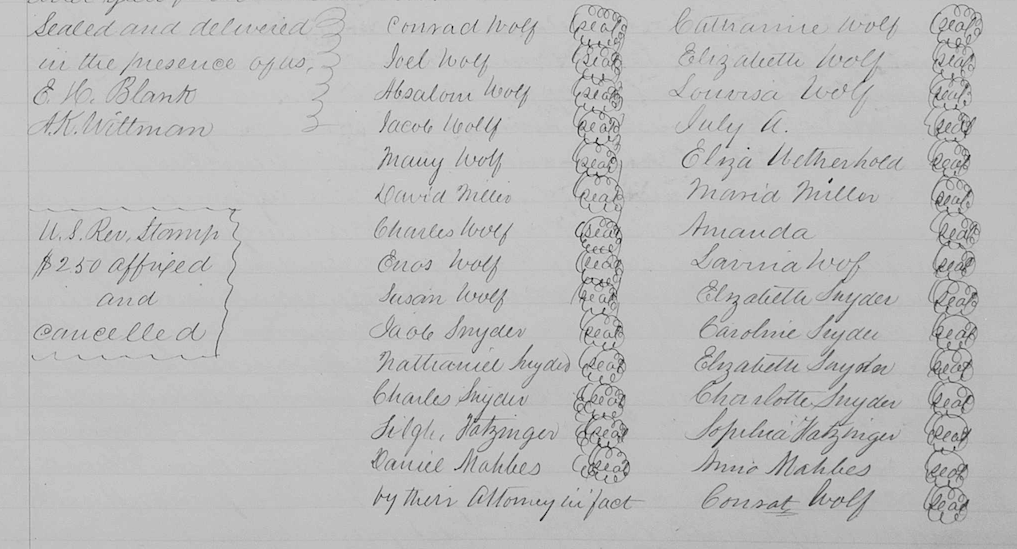

Conrad Schneider of Upper Salford Township is a possible grandfather for Jacob Schneider. He owned property near the Upper Salford and Marlborough township line, I believe, just south of present-day Sumneytown.1 On 12 July 1759, Conrad wrote his last will and testament in German. It was translated and proven about a month later on 10 August.

It reads:

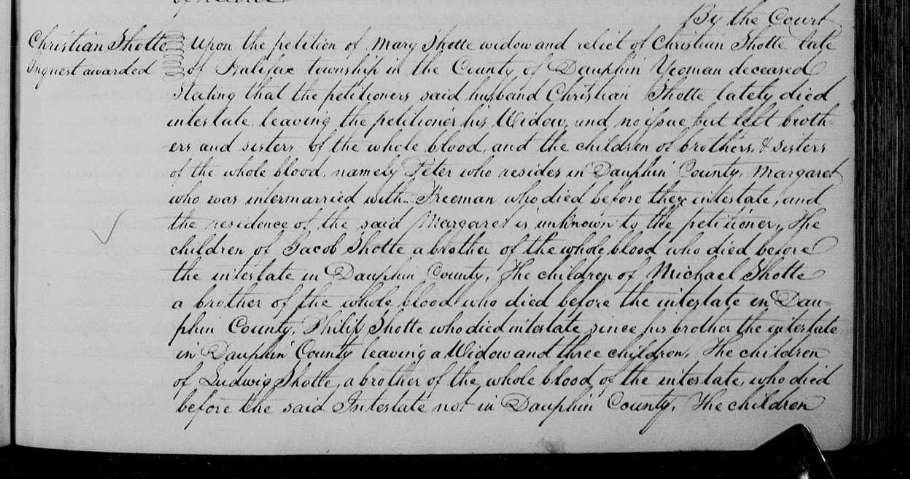

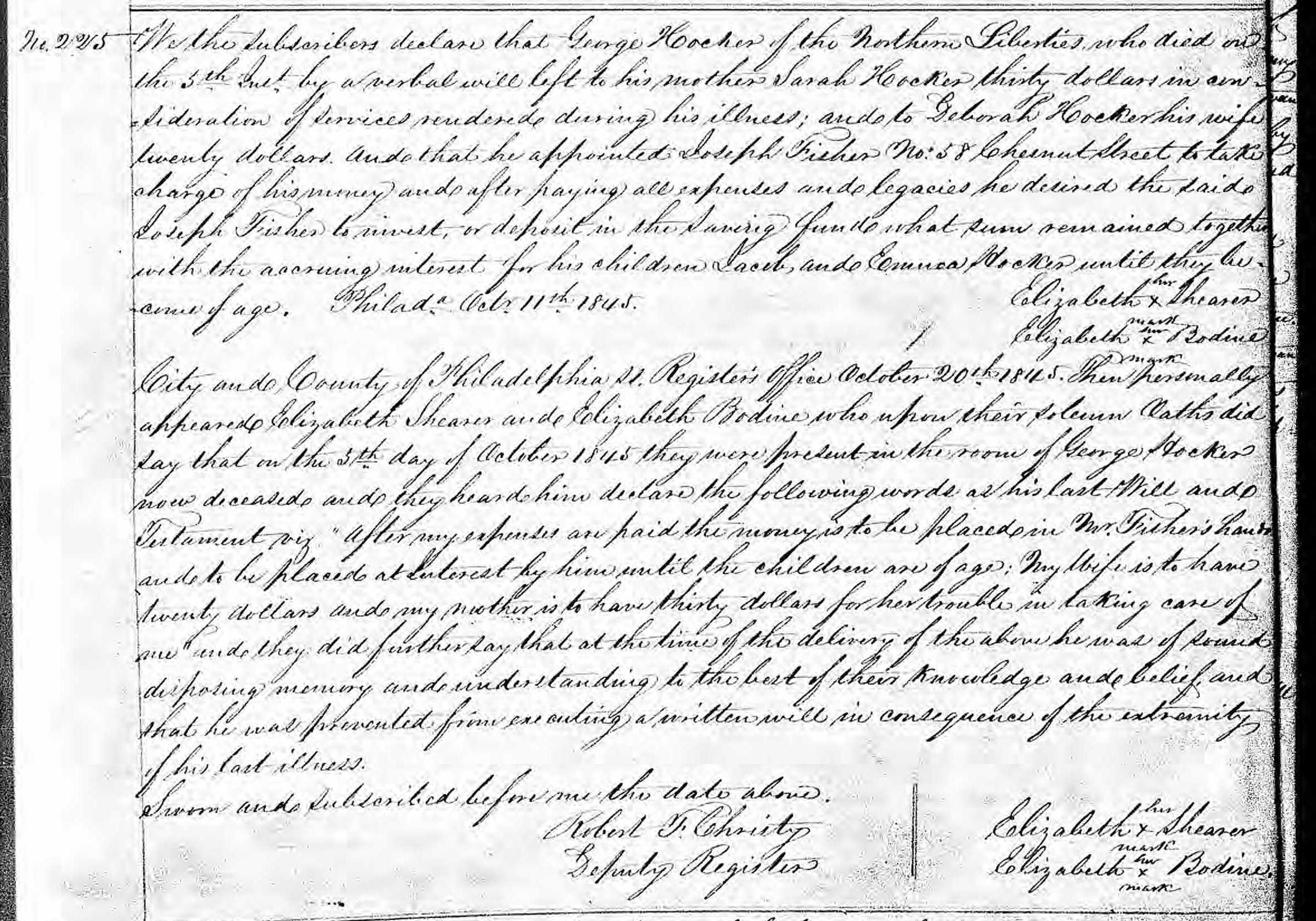

“In the Name of God the Father, the Son and the Holly Gost Amen.

I Conrad Schneider of Old Coshenhoppen Upper Salford Township in the County of Philadelphia being blessed be God, of sound mind memory and understanding but knowing that it is appointed for all Men once to dye which cant be avoided, Have made my Last Will and Testament which is to be put in Execution according to my Desire having myself subscribed the same, that is to say, Firstly my son Leonard Schneider shall have as following at first he shall have the forty acres of Land whereon he dwells and on which the House stands and these forty acres he is to have with a free Deed. These forty acres are bounded by Killian Gaughlers land and with them he is to have seventy acres more without a Deed it lies at the side of Daniel Hiesters land and it runs and is bounded by Francis Hardmans land For which the said Leonard Schneider is to pay at the Rate of one Pound for ever acres and which will amount to the sum of one hundred and ten Pounds in the Whole and he is to pay in ready Cash next Fall Fair that is to say on the twenty seventh Day of November 1759 the sum of forty Pounds and as for the remaining sumt that is to say as for Forty Pounds more thereof he is to give a Bond without any Interest payable in three years hence And the remaining fifty Pounds it shall go towards his Heritage. This is to give notice that the sum of money which was paid for the said Forty acres being twenty pounds is included in the above sum. Secondly, All my remaining Children are to share equally the Daughter as well as the sons and neither of them shall have any Advantage let it come as high as it will And if anyone of my sons will undertake the management of my Plantation then he is to pay his Sister and Brothers such sums of money as they amongst themselves shall or may agree upon and all my Children shall fair alike and

[next page]

one shall have no more than the others, that is to say, The first is named Leonard, the second Catherine the third Elias the fourth Michael the fifth Balthasar and the sixth Henry.

Thirdly my dear wife shall have for her maintenance as follows The one who gets the Plantation let him be any of my Children or a stranger, is to pay her every year during her natural live as follows, that is to say eight Bushells of Wheat eight Bushells of Rye on Quarter of Flax, which he who gets the Plantation must sow, pull, thrash and brake and she is to have one fourth art of the garden And in Place of Meat he who gets the said Plantation shall pay her yearly twenty shillings in Money, He shall also give her one half Bushel of fin Salt and every Week as longs as she lives one Pound of Butter if she desires it and if it serves her And the one who gets the said Plantation shall also pay her yearly the sum of five Pounds lawful Money of Pennsylvania and shes shall have a Place of abode in my House during her life clear of all cost as well in the Parlour, Kitchen and Cellar as at any other Part of the said House, But is she wishes to live some where else then she shall have Liberty to live wherever she likes best and in that case she shall also have all what is above mentioned yearly for her maintenance notwithstanding And if she shall happen to get sick and to keep her Bed so that she will not be able to help herself then the Person whoever keeps her shall not be troubled with her for nothing but the Person shall have such Reward as the said Sister & Brothers amongst themselves shall judge reasonable and this is my sincer Wil land the same shall be put in execution so as it is writ down And she shall more over have the sum of twelve Pounds out of my personal Estate.

Fourthly, I chuse to this my Estate or Riches my Good neighbour and Freinds John Kantz and Killian Gaugler Guardians/or * Executors/ And I do hope they will take Care of my dear Children and wife and act so as the my safely answer before god almighty and that they will not occasion the widows and orphans to cry to Heavens nor draw Vengenan[?] on themselves. The above instrument I do subscribe with my

* The German word vormunder, is properly Guardian, but by the construction of the will it seems to me that the Testator meant Executors. P Miller

[next page]

my own Hand before Evidence as and for my Last Will and Testament and as such it shall remain Done at Upper Salford July 12th 1759•1•

Conrad Schneider

George his W mark Wyand

I the subscriber so certify the foregoing Writing to be a true and genuine Translation of a German [?] Writing said to be the Last Will and Testament ^ of Conrad Schneider. The same sa[y] me having been translated from the said original by me this 10 Augt 1759

P Miller”2

Conrad, unlike some of my ancestors, was kind enough to name his children in his will. He also listed them in order: “The first is named Leonard, the second Catherine the third Elias the fourth Michael the fifth Balthasar and the sixth Henry.”3

So far, my genetic research has found descendants of Catherine and Balthasar with whom my Mom shares DNA. There are other members of the cluster I found on AncestryDNA, as well as others on GEDmatch and MyHeritage who triangulate with known descendants, who I have not yet been able to trace. All told, I think I’ve found about 14 individuals who share descent from Conrad Schneider.

I’m still trying to figure out how Jacob descends from Conrad. Based on the list in Conrad’s will and his desire that all “my remaining Children are to share equally,” it’s hard to argue that Jacob could have been his youngest son. My working hypothesis is that Elias and his wife Anna Maria Nuss were Jacob’s parents. However, I still have no evidence—and I mean zip, zilch, nada—other than proximity and the genetic link to prove this theory.

I can only hope to find descendants of Conrad’s sons Leonard, Elias, Michael, and Henry who are matches to Mom. Maybe there’ll be enough of a difference in the shared amount of DNA to point the way to one of them. But, since Conrad would be her 6 times great grandfather, it’s a bit of a long shot.

If you’re a descendant, please test. If you already have, please drop me a line. Maybe we could work together to solve this puzzle.