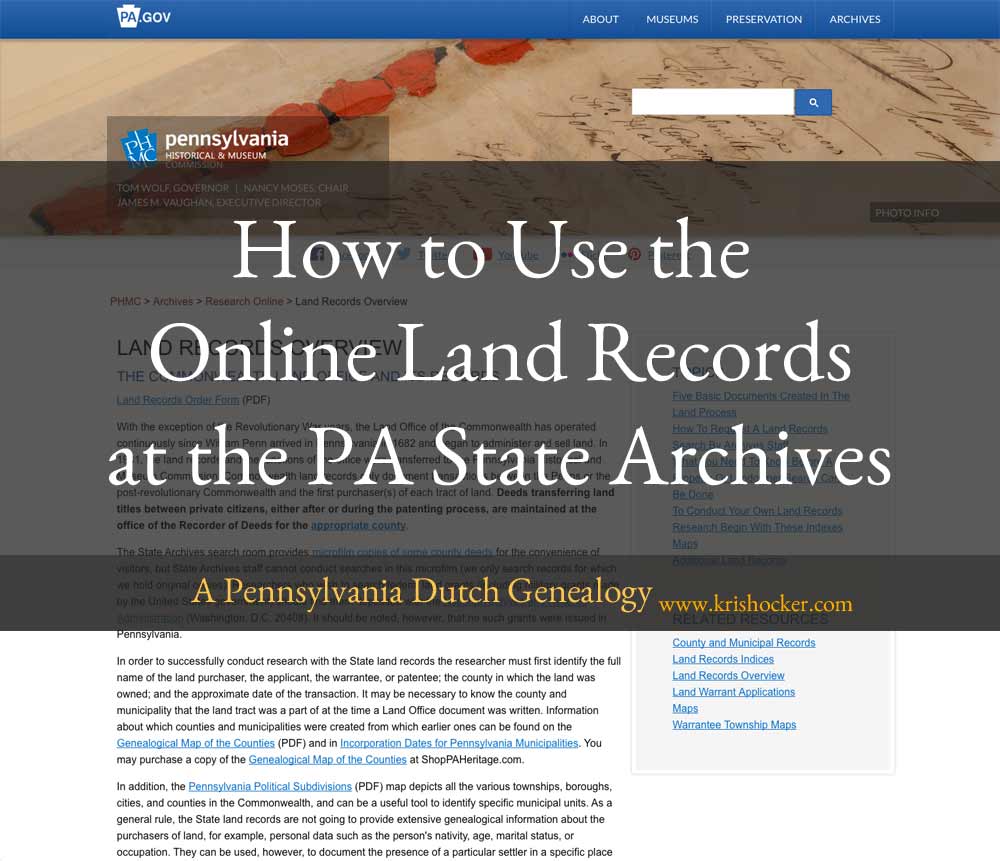

If you’ve read my blog, you’ll know that I use land records—a lot! I’ve mentioned warrants, patents and deeds in a number of posts. They’re some of my favorite record groups. And best of all, depending on where your ancestor lived, the records may be available online for free.

This blog post is going to explain how to use the land records available online at the PA State Archives. These records are organized by record and then either by county or volume and surname. They have been scanned and placed online as PDFs by page. The records include:

- Warrant Registers

- Copied Survey Books

- Patent Indexes

- Patent Tract Name Index

- Indexes of Selected Original (Loose) Surveys

- East Side Applications (Register)

- West Side Applications (Register)

- Philadelphia Old Rights (Index)

- Old Rights Index: Bucks and Chester Counties

- New Purchase Register

- Original Purchases Register

- Last Purchase Register

- Luzerne County Certified Townships

- Donation Lands

- Depreciation Land Register

- Warrantee Township Maps

- Melish-Whiteside Maps

I’m going to focus on the records in bold.

To understand how to use these records, it’s important to understand how the process worked in Colonial Pennsylvania. Technically, William Penn owned all of the land in Pennsylvania. A settler would apply to the land office for land. Before 1687, these applications were typically oral and not recorded. After 1687, they were recorded in the minute books of the Commissioners of Property. The minutes can be found in Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, Volume 19 and Third Series, Volume 1.

After the application, a warrant was issued to authorize a survey of the land. The warrants I’ve seen specify the name of the warrantee, the location of the desired property (sometimes rather generally), the amount of land, the quit-rent—and sometimes the date from which the rent commences—and the price per acre. The issuance of a warrant, however, does not mean that the applicant actually owned the property.

When a warrant was issued, orders were sent to the surveyor to survey the property and draw a map of the courses and bounds, the acreage, and the neighbors. After a survey was done, the applicant would have to pay for the land and provide evidence of their improvements to the property. In viewing the survey books, there are sometimes multiple surveys of a tract of land. Sometimes the original applicant failed to follow through, sometimes they sold their “rights” to someone else prior to the patent, or sometimes subsequent owners required a re-survey.

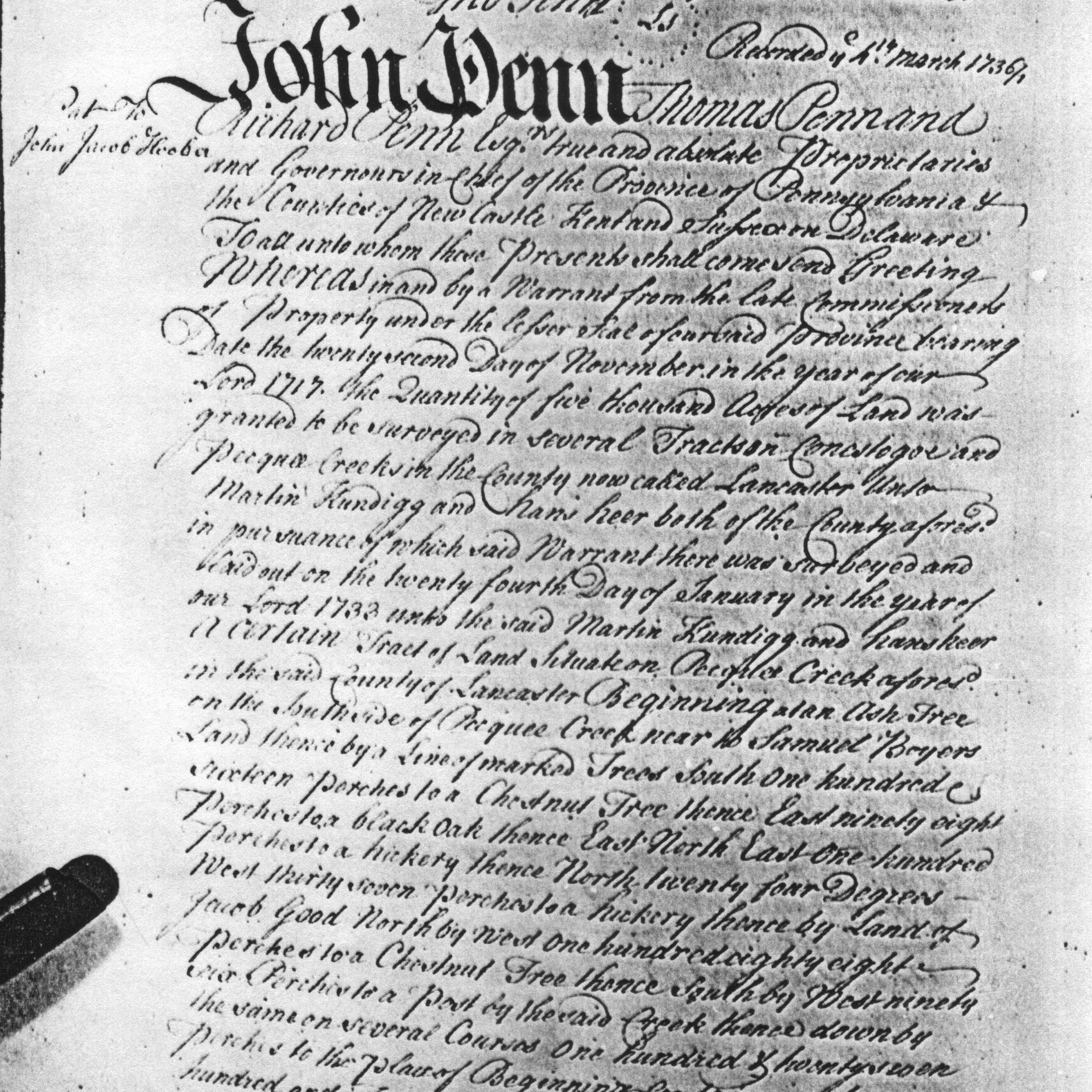

Once the survey was complete and the land paid for, a warrant of return was sent to the surveyor general, who in turn sent the survey to the secretary’s office so that a patent could be issued. The patent is the document that transferred ownership of the property to the settler.

So, warrants, patents and surveys deal with transfers of land between the Pennsylvania land office and the settler. Records of land transferred between individuals will be found—if recorded—at the Recorder of Deeds for the appropriate county. This may not be the same as the modern county. For more information on the historical transformation of the counties, take a look at the Genealogical Map of the Counties.

Patents

Ulrich Hoober, Patent Book A11:408

If you know that your ancestor received a patent for their property, you can begin with the Patent Indexes. How would I know that, you ask. Often, deeds—sometimes several transactions removed from the patent—will reference the original patent for the property. You may have seen something like:

It being the same tract of land which the late Proprietaries of Pennsylvania by their Patent dated the twenty eighth day of September A. Dom. 1744 and recorded at the Rolls Office at Philadelphia in Patent Book A vol 11 page 408 &c did grant & confirm to Ulrich Hoover his heirs and assigns forever…

If you haven’t seen a reference like this, but want to know if your ancestor was an early landholder, the Patent Indexes are still a good place to start. The Patent Indexes will not only provide the patent book, volume and page number for a patent, but will also identify the name of the original warrantee and the date of the warrant. This will make it possible to locate the warrant and survey if your ancestor was not the original warrantee.

- First, go to the Patent Indexes page on the State Archives site. The records are arranged by series, which are arranged by date. Choose the series you want to review.

- Next find the list of pages for the first letter of your ancestor’s surname. Be prepared to check multiple spellings if they apply. I’ve found “Brenneman” listed under both “B” and “P.”

- Check the available pages to see if your ancestor is listed. Each page is a separate PDF file, so you may need to download and open each file in Adobe Reader if your browser doesn’t have a plugin to view PDF files.

- Each listing includes: series and volume, date of patent, page number, patentee name, area in acres and perches, name of warrantee, name of tract (if available), date of warrant, and county.

If you find your ancestor, make note of the series, volume, page and date of the patent. You’ll need this information if you want to order the patent from the Archives. You should also note the name of the original warrantee, the date of warrrant and the county. This will be necessary for the next step.

In the image above, we have a patent for Woolrick Hoober, dated 20 Sep 1744, with 226 acres in Patent Book A11, page 408. We can also see that he is listed as the original warrantee for a warrant dated 19 Sep 1744 in Lancaster County.

Warrants

Woolerick Hoober, Warrant H338, Lancaster County

Now that you have the name of the warrantee, warrant date and county, you can look-up the warrant and survey information in the Warrant Registers. These registers cover approximately 70% of all land in Pennsylvania for 1733—1957. If the warrant date is 1733 or later, follow these instructions.

- Go to the Warrant Registers page on the State Archives site. The registers are first arranged by county. Click on the link to the appropriate county.

- The pages for each register are listed first alphabetically by the first initial of the warrantee’s surname, then chronologically.

- Check the pages to see if the warrantee is listed.

- Each listing should include: warrant number, warrantee, type of warrant, quantity of land, warrant location, date of warrant, date of return, acreage returned, name(s) of patentee(s), where the patent is recorded (book, volume, page), and where the survey was copied (book, volume, page). Sometimes there are multiple patentees or surveys for each warrant. Sometimes the warrant was vacated and no information is available.

Woolrick Hoober’s listing tells us that he was issued a warrant (#338) to accept a survey of 226 acres in Conestoga Township, dated 19 Sep 1744. The patent was issued 19 Sep 1744 on 226 acres. The patent is listed in Book A11, page 408 and the survey is in book D88, page 127.

If the warrant date was before 1733, you’ll need to check the Old Rights Index for Bucks and Chester counties or the Philadelphia Old Rights Register.

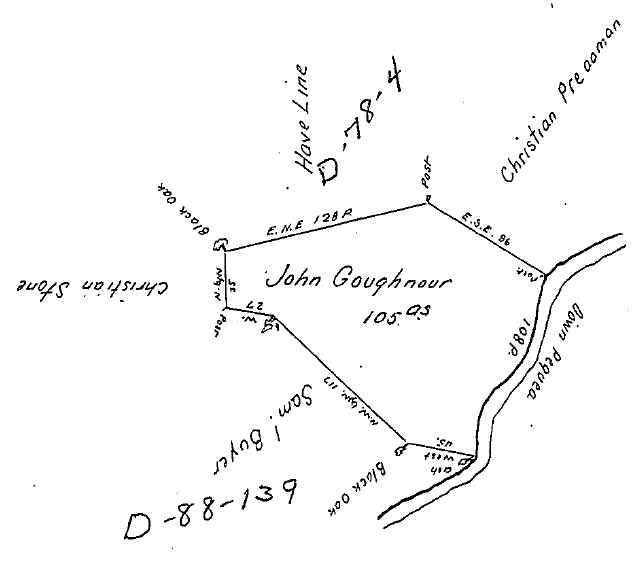

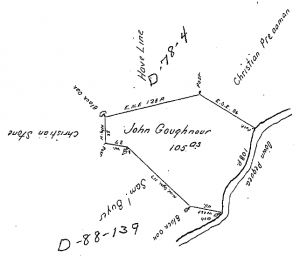

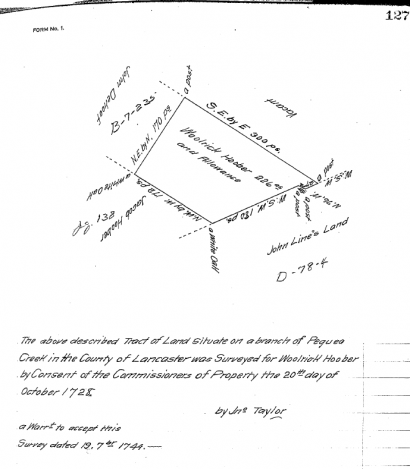

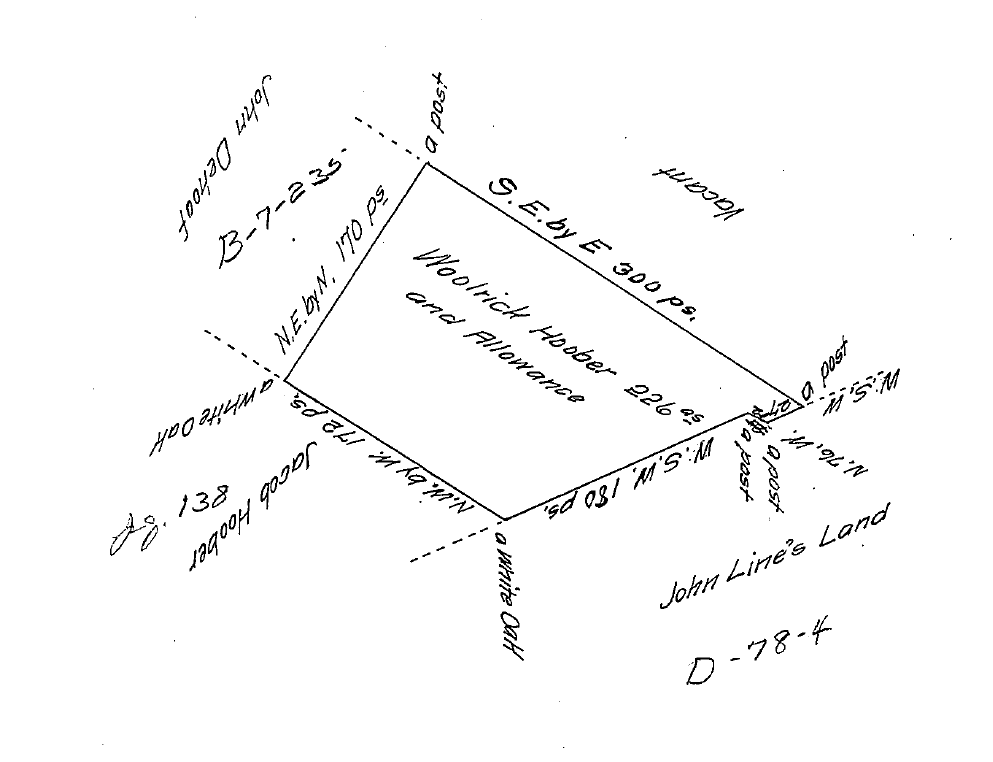

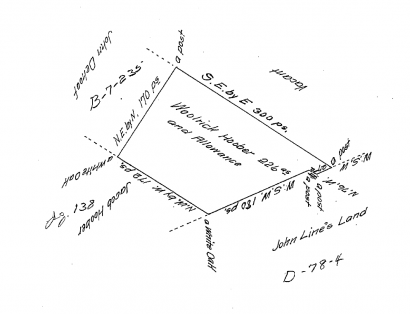

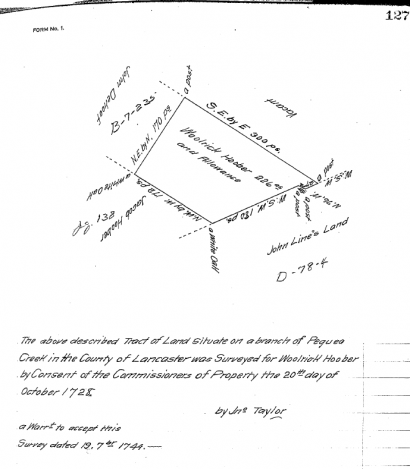

Surveys

Woolrick Hoober, Survey Book D88:127

With the location of the survey from the Warrantee register, the next step is a piece of cake.

- Go to the Copied Survey Books page.

- Select the appropriate page for the book and volume.

- Click on the page link.

- Each survey should provide either a description of the metes and bounds or a drawing of the tract’s boundaries with the calls and the names of the tract’s neighbors. The survey also usually shows the date of the survey, name of surveyor, who the land was surveyed for, the date of the warrant, and the warrantee.

Ulrich’s survey shows that John Line, Jacob Hoober, and John DeHoof were his neighbors at the time of the survey—20 Oct 1728.

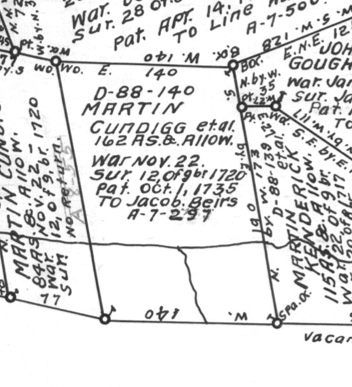

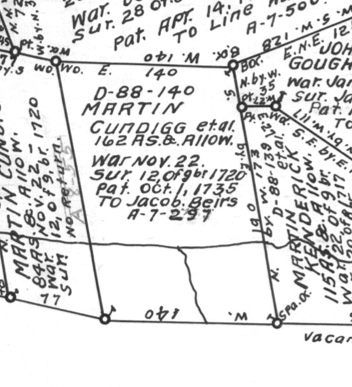

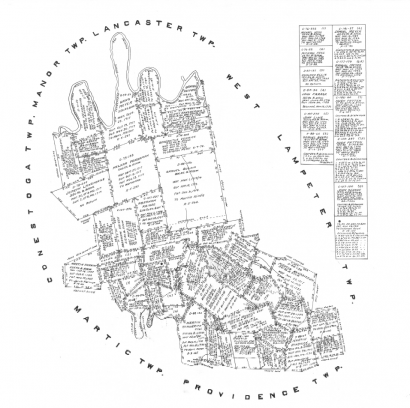

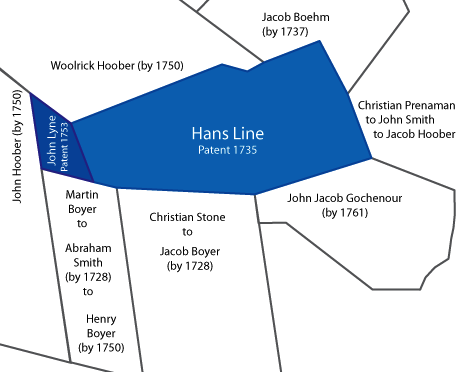

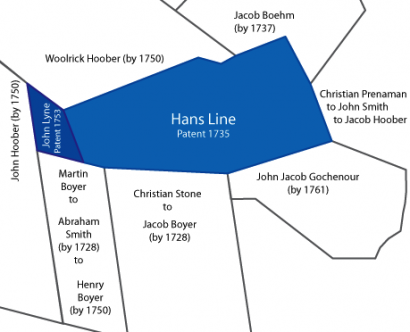

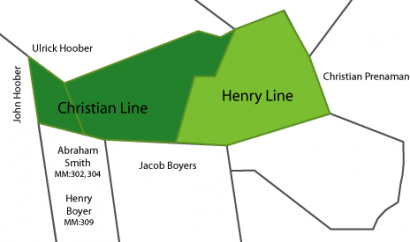

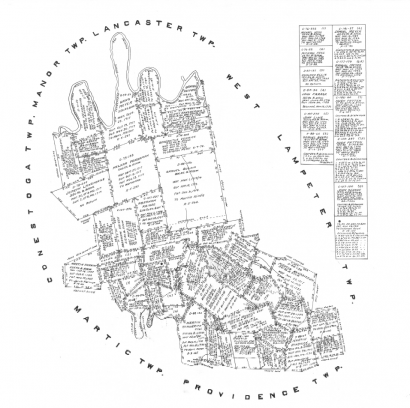

Warrantee Township Maps

Maps for some of the townships were drawn up showing all of the original landholders—those who received the property directly from the Proprietors or the Commonwealth—within the context of the present-day townships. Unfortunately, not every township was mapped.

Pequea Warrantee Township Map

To find a map of the township were your ancestor held property, you need to know the relationship between the historical township and the modern township. For instance, Ulrich Hoober’s tract was in Conestoga township when he received the patent in 1744. Two modern townships—Conestoga and Pequea—make up the historical 1729 township. You can see Ulrich Hoober’s property in the context of the township’s other properties in the Pequea Warrantee Township map.

Don’t forget, using this information you can order a copy of the land warrant or patent from the Pennsylvania State Archives. If you know the reference—warrant number, warrantee and county of warrant for warrants or patentee, patent date, book, volume and page number for patents—you can order an uncertified copy fairly inexpensively. If you don’t have that information, you can also order a search by the staff archivist. That, of course, will cost you more. Warrantee township maps are also available for sale.

If you can visit the state archives in Harrisburg, you can use the information you found through the online records to locate the documents on microfilm, saving time looking up the references so you can research other records.

That’s a fairly quick explanation of warrants, patents and surveys at the Pennsylvania State Archives website. These instructions should work for most properties. However, there will be exceptions (aren’t there always?). If you have questions, leave a comment or drop me a line. I’d be glad to help however I can.

Note: modified to include new PHMC screenshot.