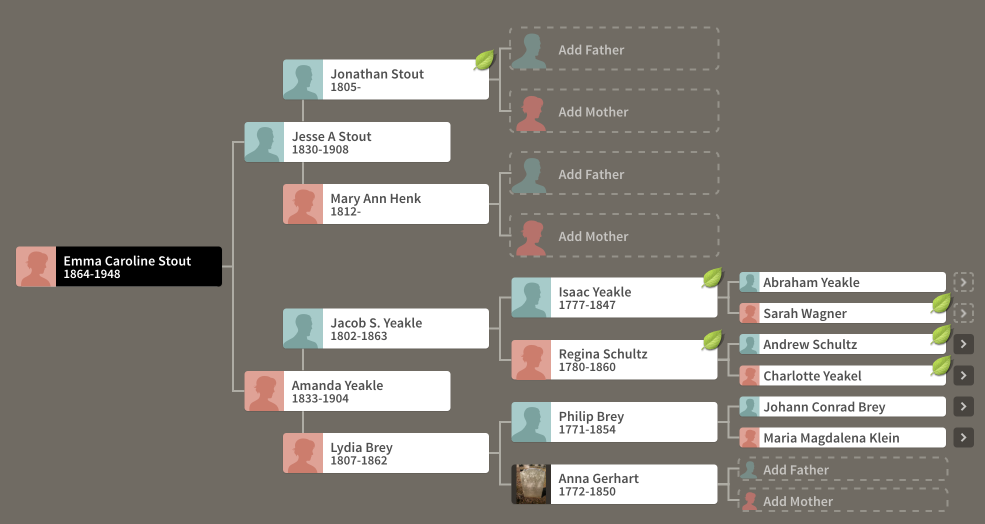

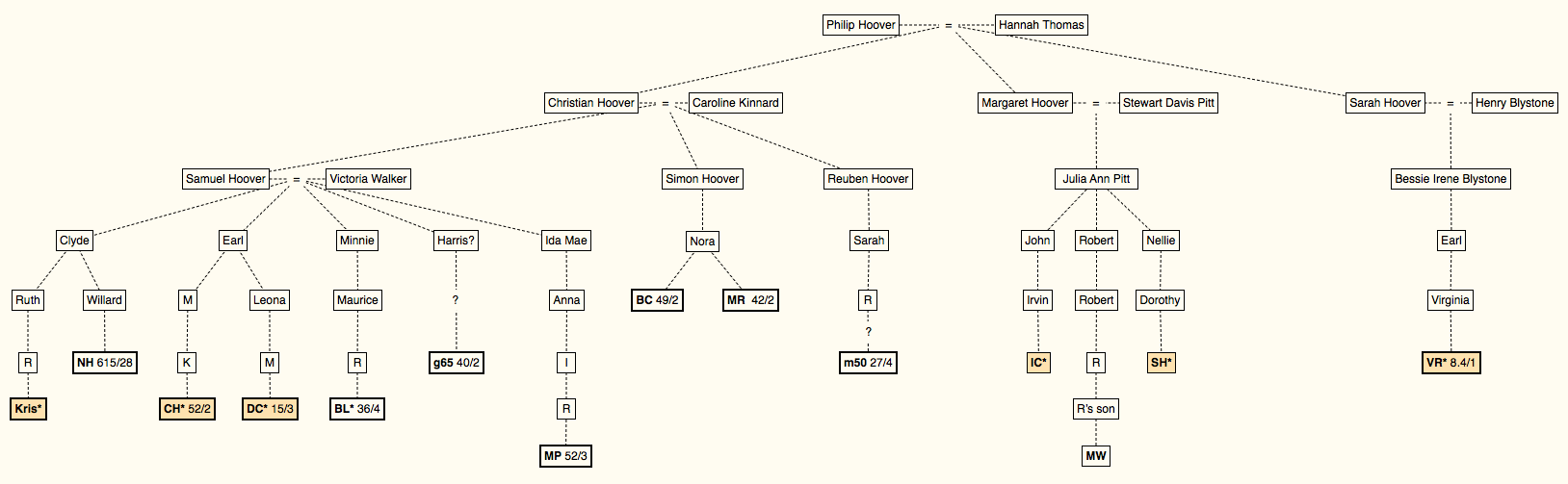

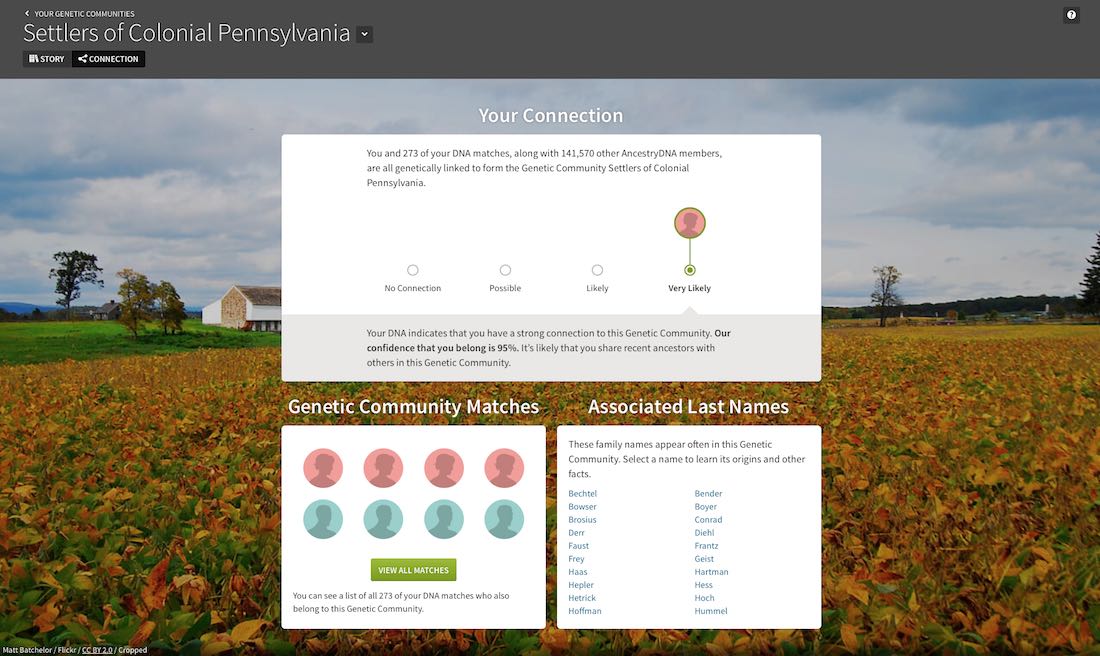

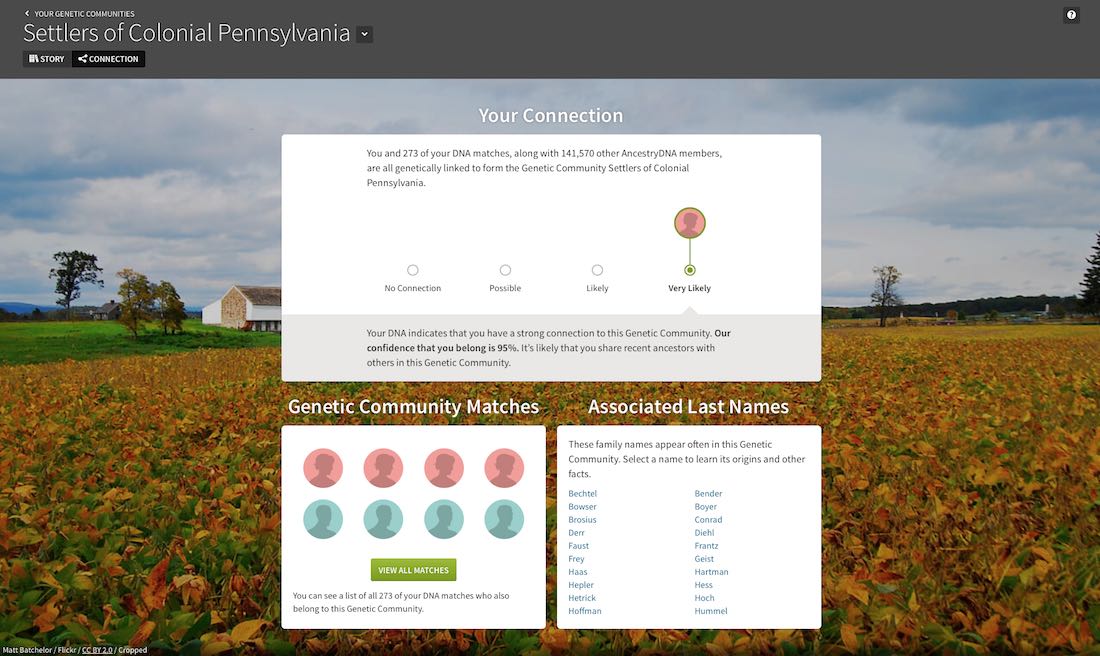

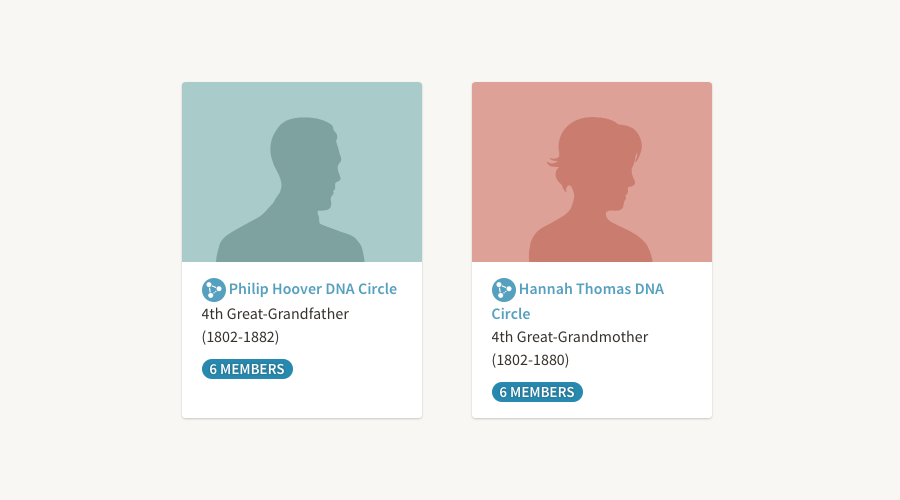

As I reported last year in “A Beautiful Circle,” I am a member of both the Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas circles on AncestryDNA. This means that my DNA matches that of at least two people who have public trees in which both Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas appear within six generations as a common ancestor. Therefore, my DNA results support my hypothesis—though does not prove—that my three times great grandfather, Christian Hoover, was the their eldest son.

However, my matches from the circle include two cousins who descend from Samuel Hoover and Victoria Walker, Christian’s son, and only one cousin who descends from another child (Sarah) of Philip and Hannah. This cousin also matches two descendants from yet a third child of Philip and Hannah, Margaret, but neither I nor the other Samuel descendants match them.

I decided to see if I could find additional evidence of the connection through my other matches.

Clustering Shared Matches

Blaine Bettinger at The Genetic Genealogist put forward a technique using the Shared Matches tool at Ancestry. By mining the shared matches of your matches, you can look for shared ancestry. Since only my Mom and I have tested, and the Hoovers are on my paternal side, I couldn’t use this technique exactly as explained.

However, what I did is not all that different, just not as thorough.

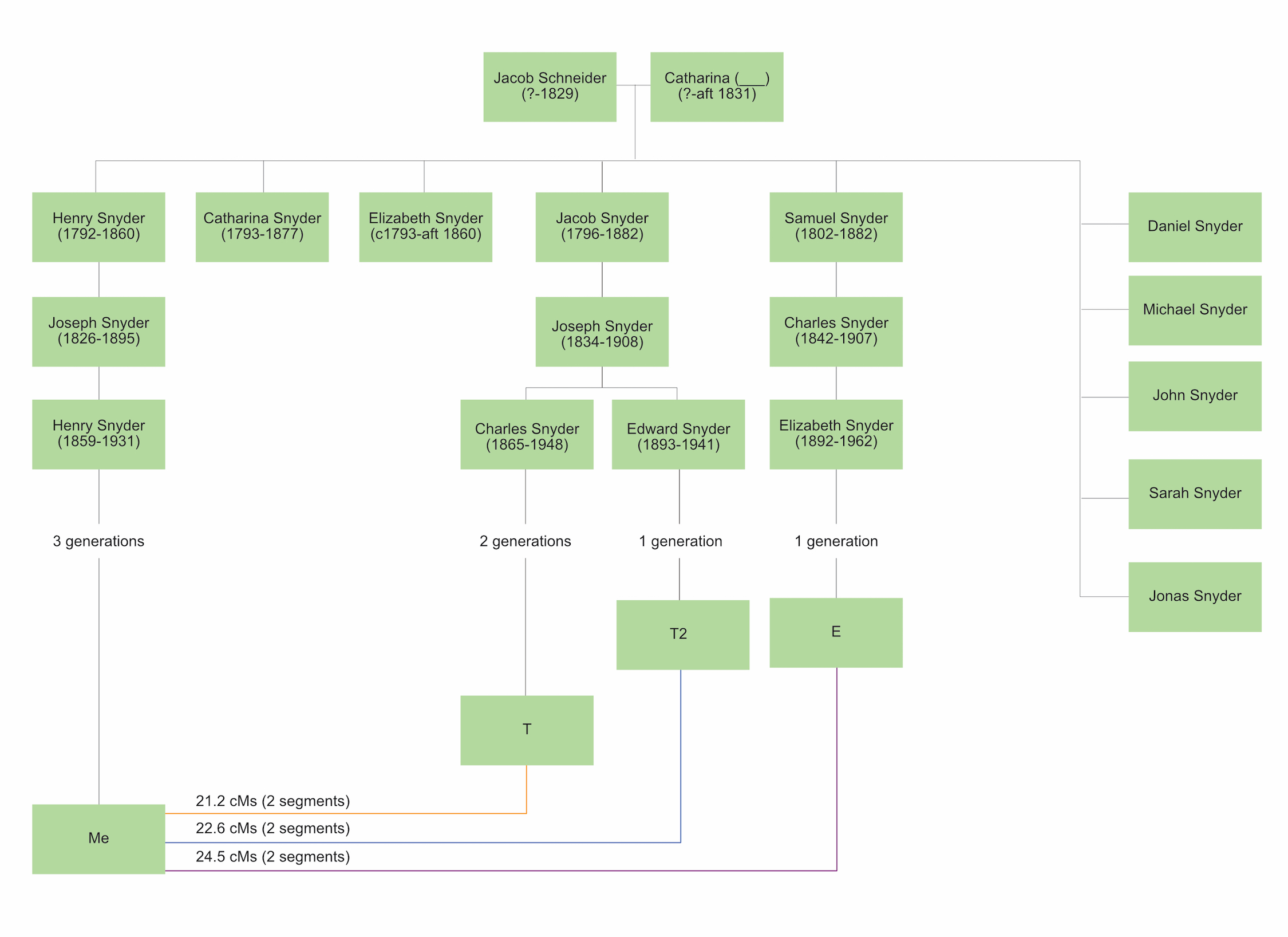

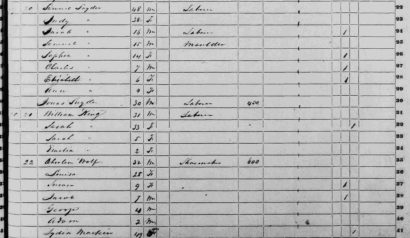

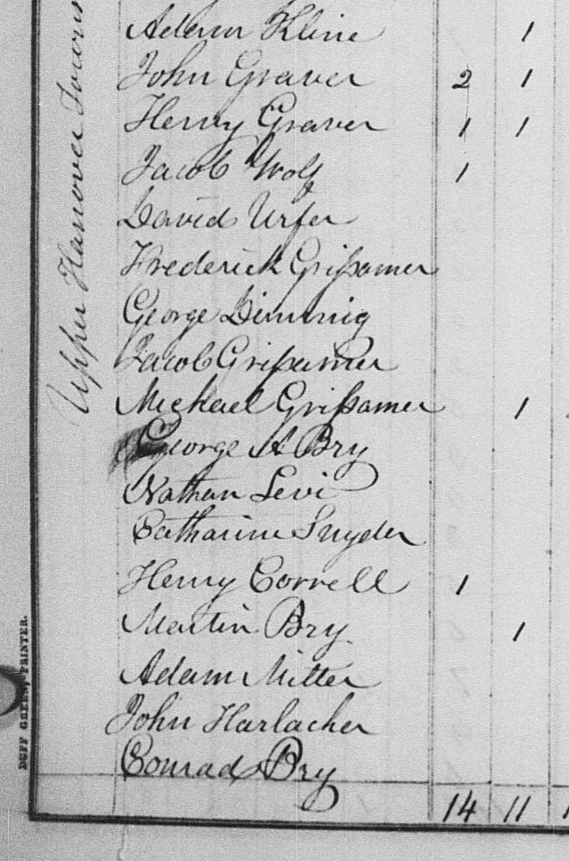

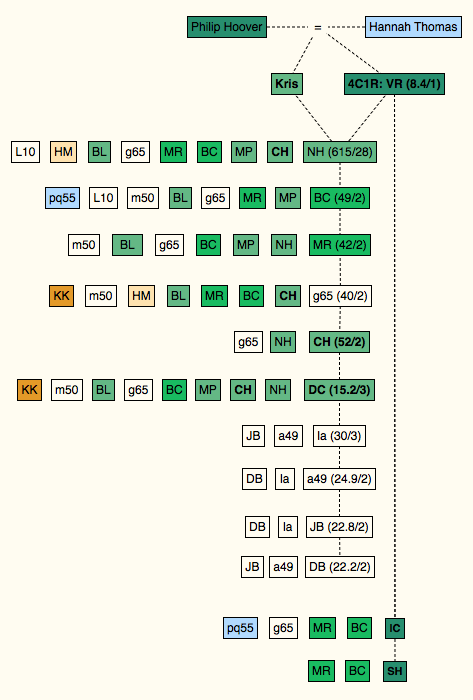

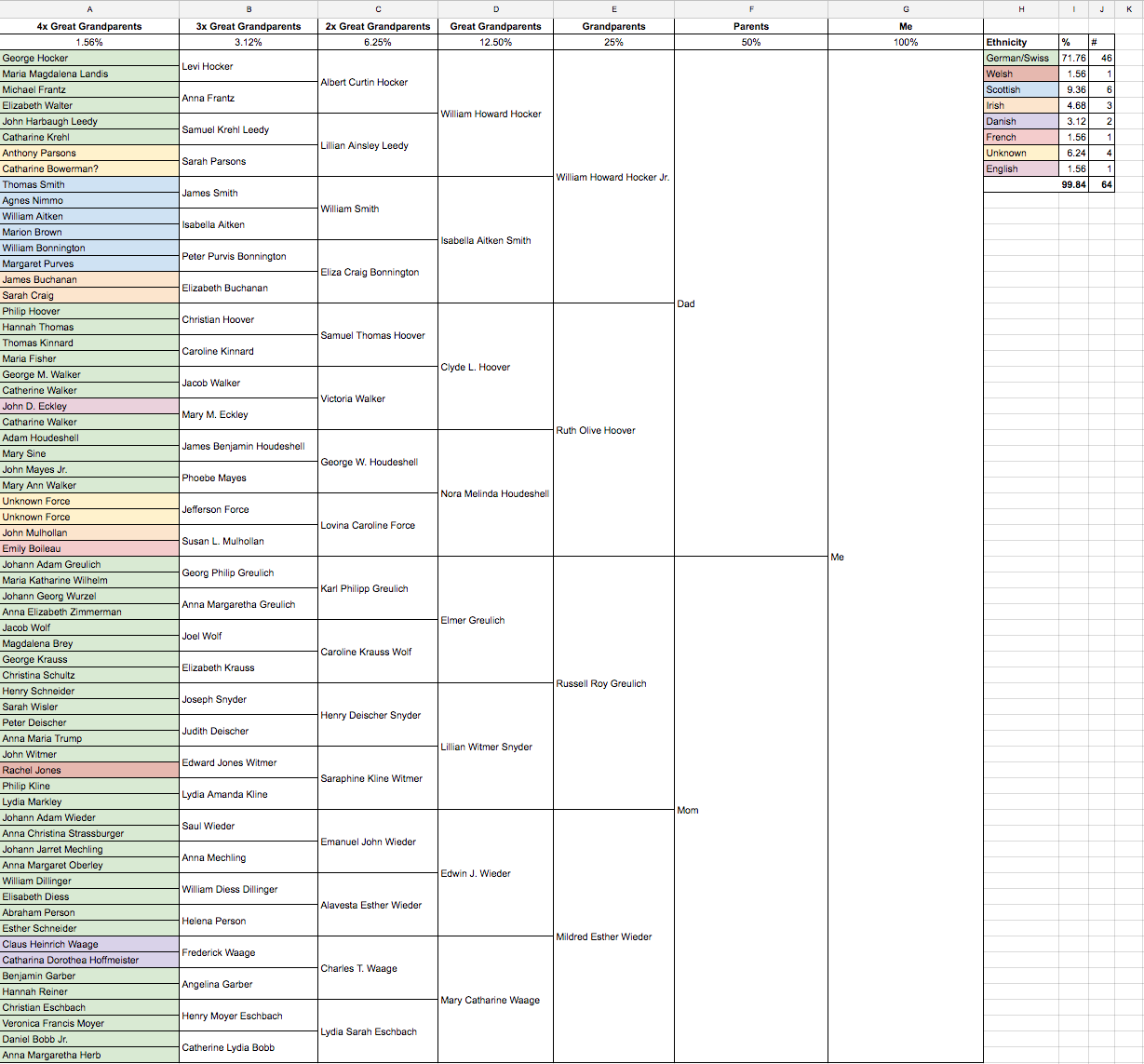

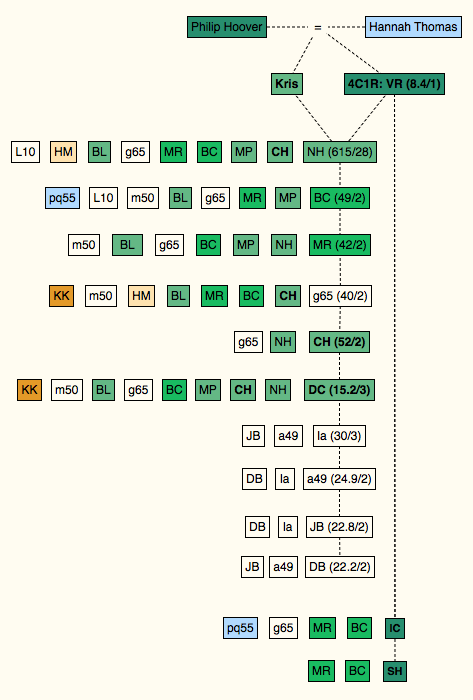

First I identified the Shared Matches between myself and the one Philip and Hannah descendant I match—let’s call them VR. There were ten. I listed them and included the amount of DNA and the number of segments we shared. The amounts ranged from 8.4 cMs to 615 cMs, across between one to twenty-eight segments. These amounts are included in figure A and B (amount/segments). The AncestryDNA Circle members are bold.

Figure A: Hoover Shared Matches

Then for each of these people, I listed all of the matches they shared with me. If these shared matches were not also on the list of at least one of the others, I removed them from consideration.

Within the first couple, it was clear that there were going to be additional Hoover cousins on my list who were not members of the AncestryDNA circles. Several of them were easily identified because we had Shared Ancestor Hints. Those I highlighted in green. If I recognized one as being a descendant of an associated family—a Walker, Kinnard or Thomas—I highlighted them another color.

Of the ten I shared with VR, I quickly identified four of them among my Hoover relatives—three as descendants of my two times great grandfather Samuel Hoover (NH, CH, and DC) and one as a descendant of his brother Simon (BC). I also identified another two of the recurrent matches as Hoovers (MP and BL). With some research I was able to identify three more Hoovers—one positive identification (MR) and two possibles (m50 and g65). I highlighted all of those I was sure of in green.

Four of the matches I shared with VR—la, a49, JB and DB—didn’t match these Hoovers. They matched only a group of testers that they shared with each other, myself and V. As none of them had shared ancestor hints, I decided to put them aside for later consideration and further research.

I was also curious to see if any of my known Hoover relatives matched the two other members of Philip and Hannah’s circles: IC and SH. Two of the Hoovers I’d identified (BC and MR) and one of the possibles also matched them (g65).

Putting It Together

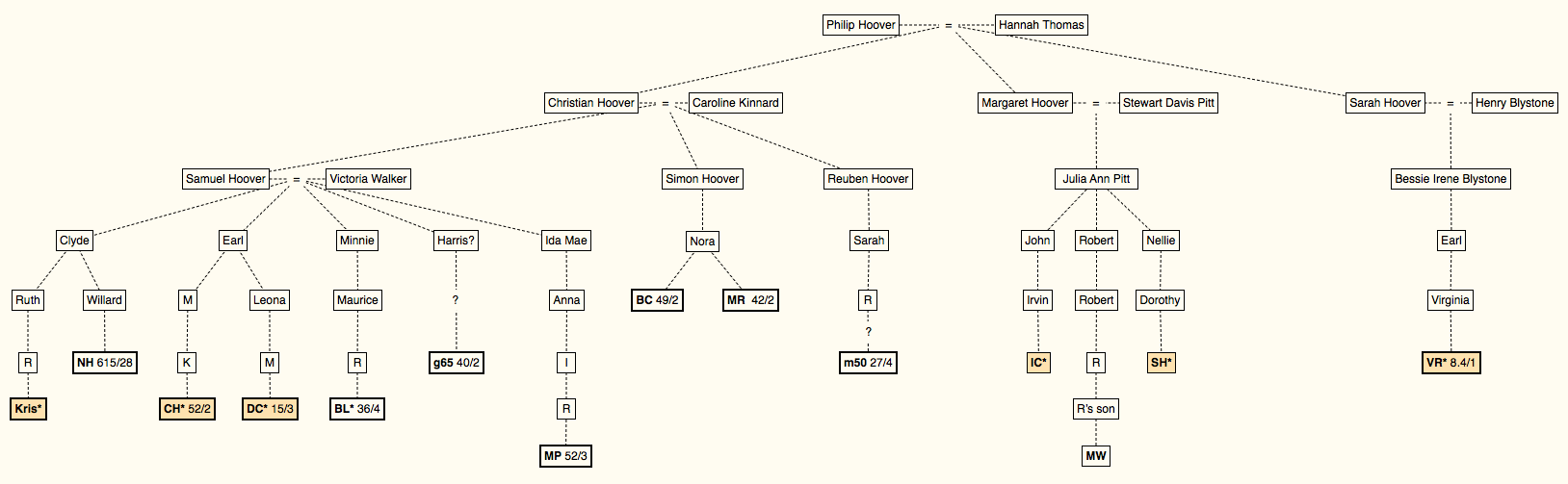

So, now I had eleven matches for whom I could identify their descent from Philip and Hannah, and two who I could, I think, place in the appropriate branches. Maybe. The chart below shows this information (click to enlarge).

Figure B: Hoover Shared Matches on tree

Based on the AncestryDNA matches, VR and I share DNA with descendants from two of Christian’s children: Samuel and Simon. These descendants and I also share matches that include other descendants of Samuel and one of Reuben’s. VR also matches descendants of Philip and Hannah’s daughter Margaret. Even though I do not match Margaret’s descendants, they match two of my matches who belong to Simon’s line and one of Samuel’s (presumably).

To my mind this is not a fluke.

The next question? Do I share DNA with each of these matches within the expected amount for each relationship?

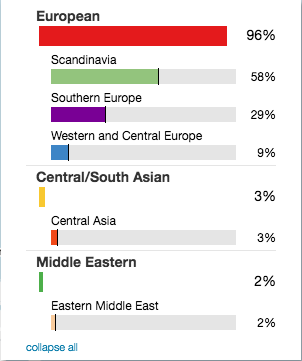

The matches include relationships as follows:

- NH (615/28) : first cousin once removed

- CH (52/2) : third cousin

- DC (15/3) : third cousin

- BL (36/4) : third cousin

- g65 (40/2) : third cousin—third cousin twice removed?

- MP (52/3) : third cousin once removed

- BC (49/2) : second cousin twice removed

- MR (42/2) : second cousin twice removed

- m50 (27/4) : third cousin once removed?

- VR (8.4/1) : fourth cousin once removed

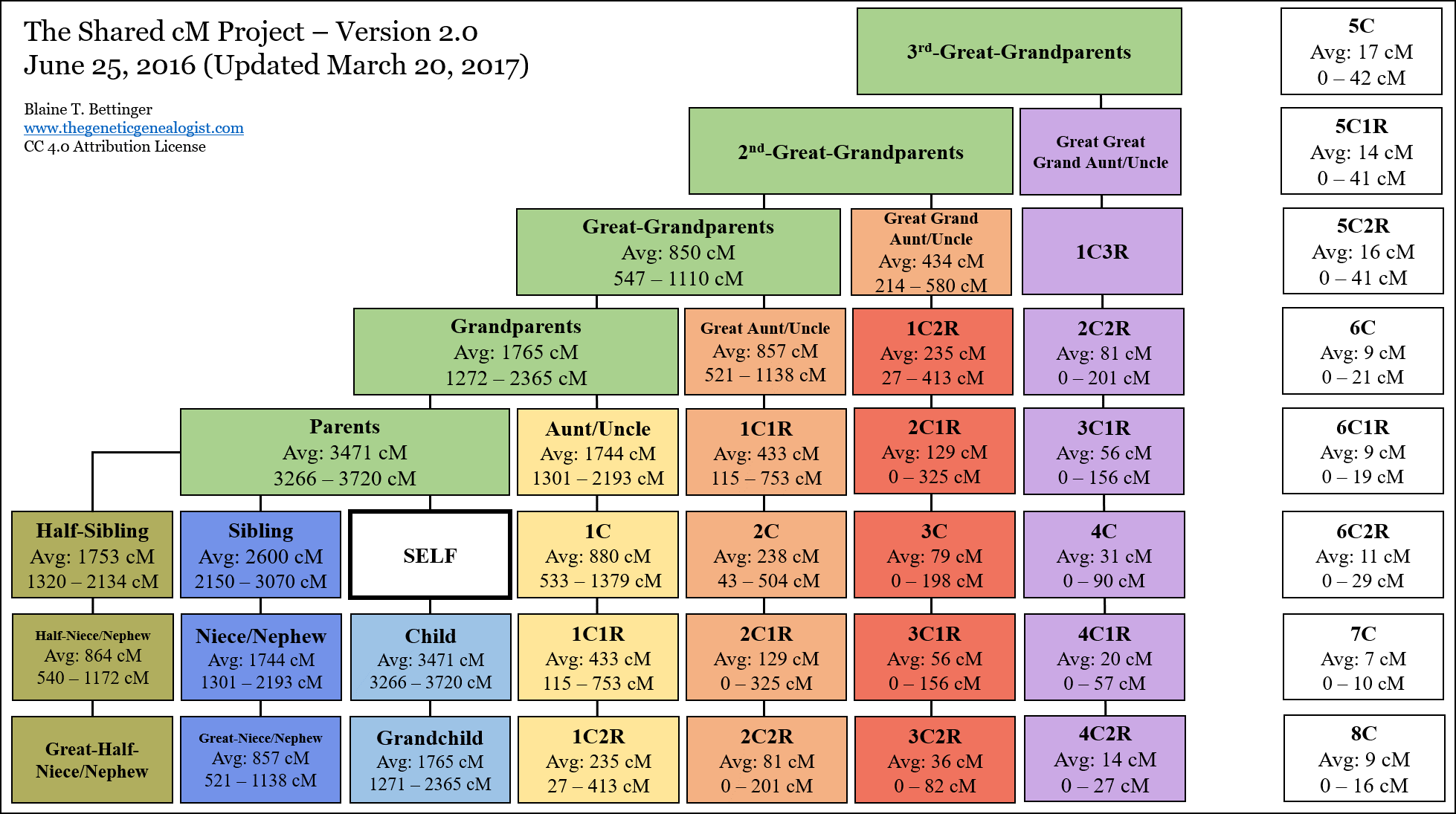

Based on the Shared cM Project, there are ranges of expected shared DNA for each relationship as shown in the following chart:

As you can see the amount of DNA I share with each cousin is lower than average in some cases, but all fall within the expected ranges for the proposed relationship. This doesn’t prove the relationship, nor does it disprove it. But, as far as I can tell, the numbers do not suggest that any of these presumed relationships are erroneous.

The Limitations

Does this prove that we all inherited our matching DNA from Philip and Hannah, and, therefore, prove our descent? No. Unfortunately, there are several limitations to this approach.

First of all, I was only able to identify my shared matches with those cousins who appeared on my shared match list with VR. I could not identify the matches shared by VR and each of these cousins. I don’t believe the other Hoover cousins I identified would have appeared on VR’s list, but maybe there would have been other’s I could have identified with whom I don’t share DNA.

Furthermore, Ancestry’s Shared Match tool only shows us people who are on both our match list and our match’s match list. The fact that we have matches in common only means that we share DNA somewhere on our chromosomes with the same people. It does not, however, mean that we share the same segments on the same chromosomes with the same people.

For instance, VR and I share both DNA with BC, so she appears on both our match lists. However, BC and I could share DNA inherited from the Kinnard family, while VR and BC may share DNA inherited from the Hoover family or another relative they share who is completely unrelated to me. It would be different DNA and wouldn’t link us genetically, but BC would still be a shared match to both VR and I. There’s no way of knowing based strictly on the data and tools available through Ancestry.

In order to prove the relationships between all these shared matches, I would need segment data for each of them. While I could use FTDNA’s chromosome browser to ensure that I matched each of these people on the same segment of the same chromosome, I could not perform the comparison to ensure that they matched each other in the same location. The only way to prove our shared DNA is inherited from Philip and/or Hannah would be to compare each of us one-on-one to be sure that we share overlapping segments. To do this, I’d need to use the tools and data on GEDmatch.

So, I guess my next step is to contact my cousins to find out if any of them is willing to upload their results to GEDmatch (it’s free!) for analysis.