On 10 February 1785, Ludwig and Catharina Schott had a son they named Ludwig in Upper Paxton Township, Dauphin County. He was baptized at Salem Evangelical Lutheran Church in Killinger. Seven months later on 3 September 1785, Ludwig’s brother Jacob and his wife Margaretha also had a son. He was baptized at St. Peter’s (Hoffman’s) Reformed Church in Lykens Valley. They, too, named him Ludwig.

One of these Ludwig Schotts married Margaretha Messner. Which one?

Ludwig Schott

Ludwig Shott married Margaretha Messner by 1811 in the upper end of Dauphin County. When he died in 1824, he and Margaret had four living children: Catharine, Susanna, John and George (a minor). By 15 November 1841 when Susanna’s husband Christian Lenker petitioned the Orphans Court for an inquest to partition Ludwig’s land, Margaret had married Philip Schott.

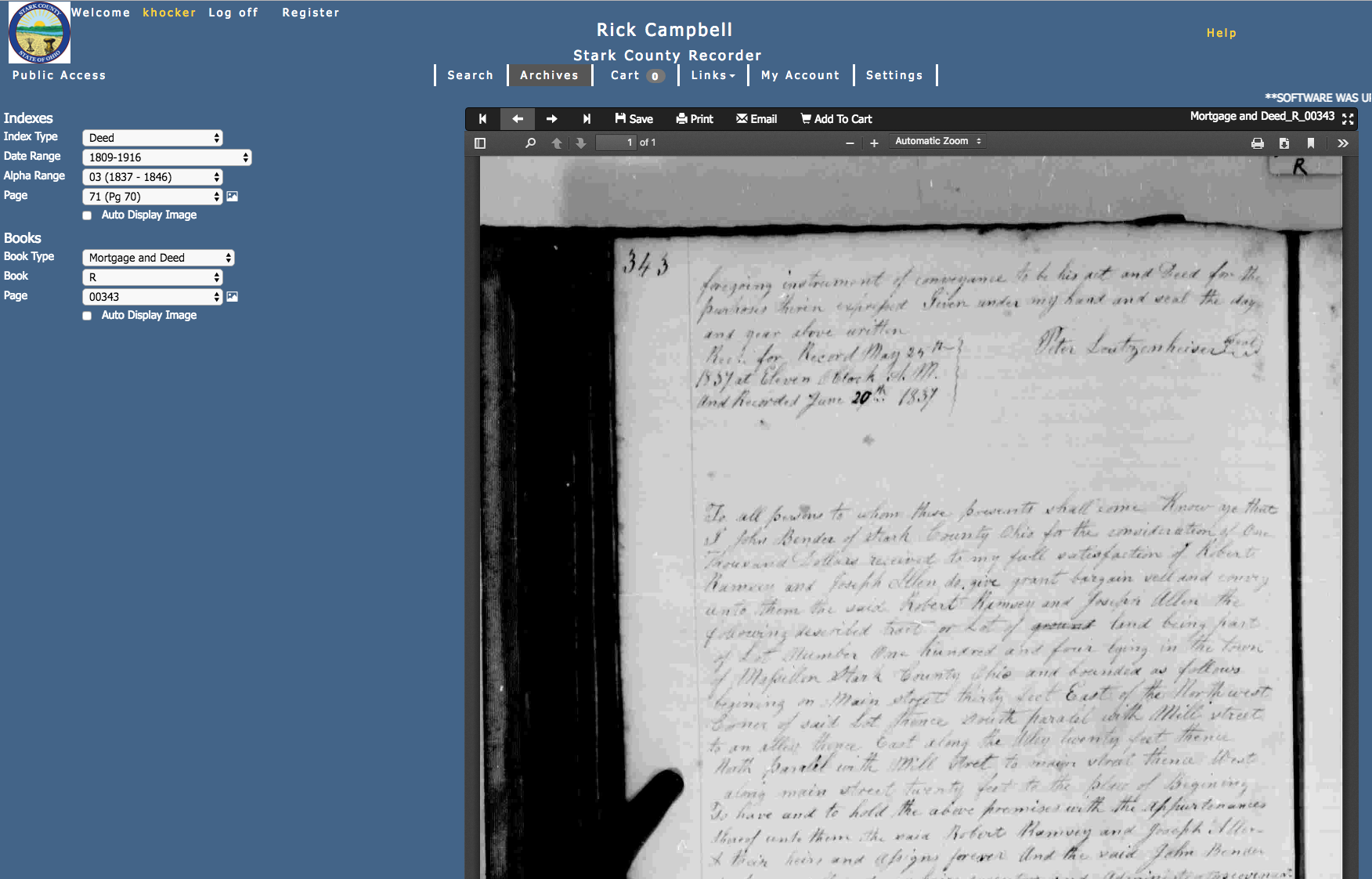

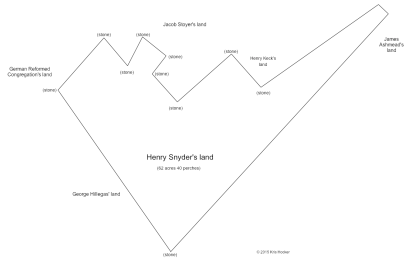

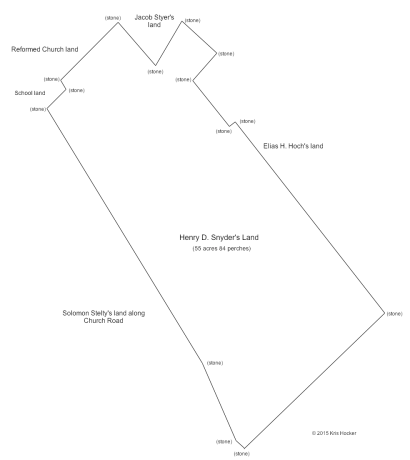

According to the inquest, Ludwig’s land was partially in Mifflin Township and partially in Upper Paxton Township. He held 110 acres 23 1/4 perches of land “bounded by lands of the heirs of Jacob Shott, Ludwich Lenker, Jacob Woland, Peter Minnich, and others” along with an interest in and share of a grist mill—“the saw mill having fallen down”—between Jacob Shott and Ludwig Shott.

Heirs of Jacob Shott? Jacob, like Ludwig, was a popular name in this family. Not only is there Jacob Shott, the father of one of the Ludwigs, but each of the Ludwigs had a brother named Jacob.

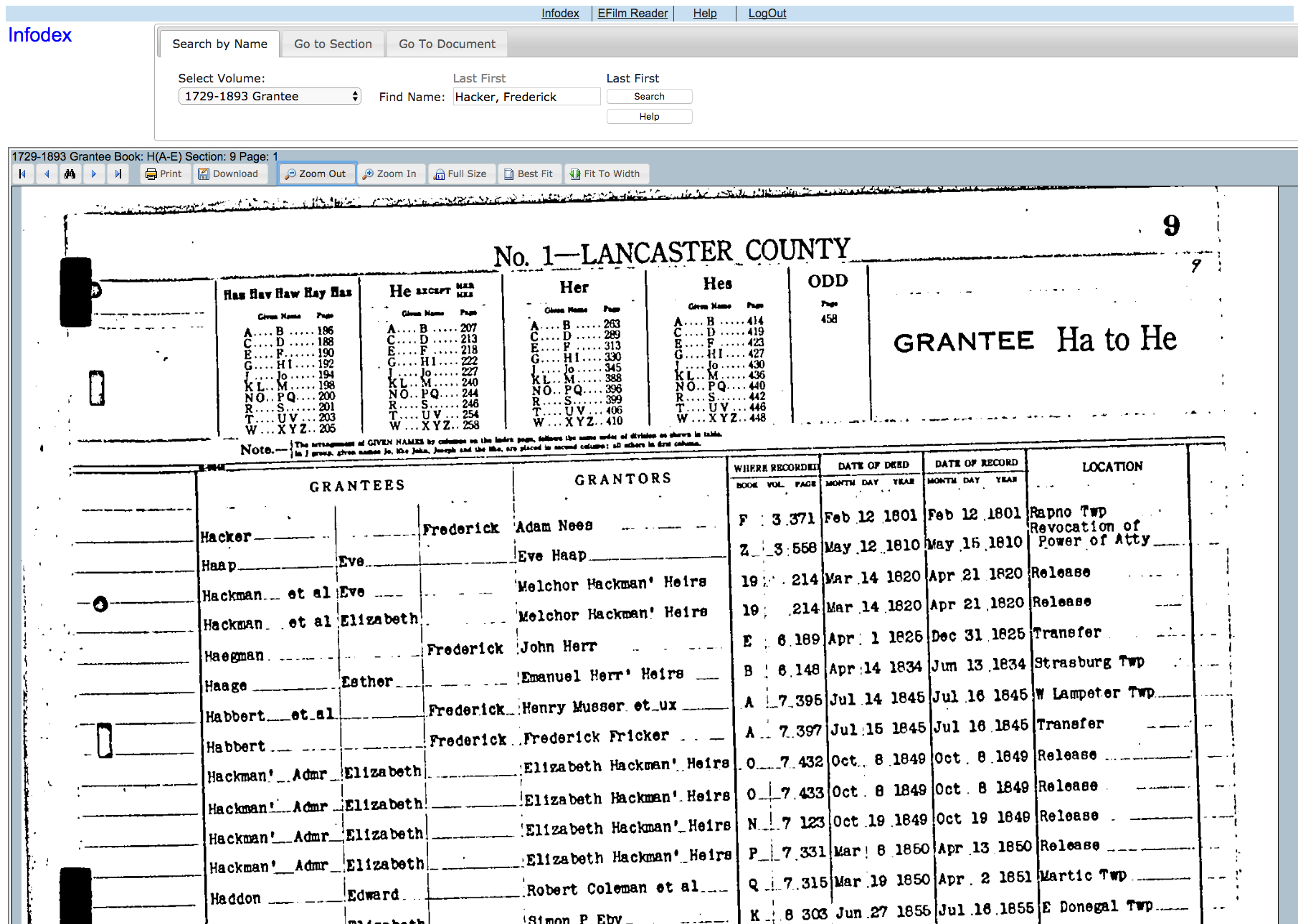

I found no record of deeds between Jacob and Ludwig Shott. However, from the probate, we know that we are looking for the Ludwig who:

1. Was married to Margaret

2. Owned land adjoining Jacob Shott, Ludwig Lenker, Jacob Woland and Peter Minnich

3. Shared ownership of a grist mill with Jacob Shott based on an agreement from 20 August 1824

Ludwig Schott, the Immigrant

Ludwig Schott Sr., grandfather of these two men, was in Upper Paxton Township, living along Wiconisco Creek by 1756. On 7 March 1756, Ludwig, along with his neighbors Andrew Lycans and John Rewalt, were fired upon by Native Americans. The men, injured, “managed to get over the mountains into Hanover Township, where they were properly cared for.” They did not return to their homes for some time.

During this timeframe, Ludwig married his second wife, Anna Barbara Laurin, at Augustus (Trappe) Lutheran Church in Montgomery County on 10 March 1757. Their first three children were born in Lancaster County and baptized at churches in Lancaster Borough.

By 1767, he’d most likely moved his family back to the Lykens Valley. He applied for 160 acres on the north side of Wiconisco Creek 24 September 1767. The land was surveyed 19 May 1768. He did not patent it. Instead, 116 1/2 acres from this tract were patented to Jacob Shott in 1843 and the other 43 by Christian Bock in 1806.

There were two additional tracts adjoining this one that were warranted to a Ludwig Shott (Shutt, Shaut), presumably the same man. The 96 1/2-acre tract directly to the north was warranted 29 August 1774 and surveyed 29 February 1775. It was patented as two pieces of land in 1806 to Christian Bock and 1834 to Philip Shutt. The tract to the south, 87 3/4 acres, was warranted 26 April 1785 and surveyed 29 May 1806. It, too, was patented as two tracts, one of 22 acres on 4 June 1806 to Christian Bock and the second of 65 1/4 acres to Jacob Shutt on 12 June 1820.

Ludwig died circa 1788. After twelve men determined that the estate could not be divided among the heirs, Ludwig’s eldest son Jacob was awarded the property by the Orphans Court with the stipulation that he pay the other heirs their share of the value of the land—£415.

Jacob Shott

Jacob Shott died intestate on 1 October 1808. His eldest son Christian petitioned the court for an inquest to make a partition of his estate. Prior to his death Jacob owned about 220 acres in Upper Paxton Township with a mill. According to the petition, Jacob left a widow named Elizabeth and children: Christian, Jacob, John, Ludwig, Peter, Philip, Ann Mary wife of Leonard Snyder, Catharine wife of John Adam Herman, and Christiana wife of Abraham Feidt.

Jacob Shott Jr.

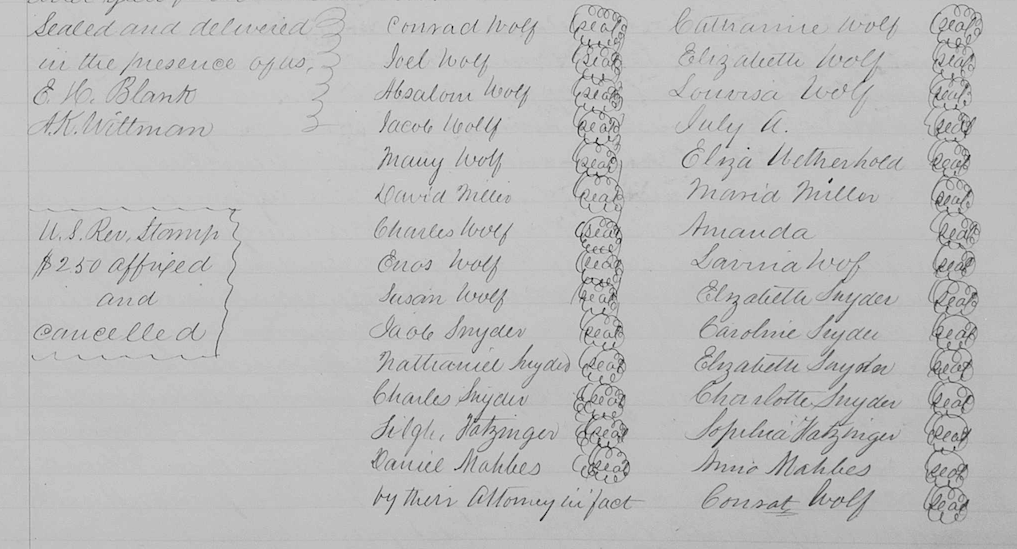

Ultimately, Christian relinquished his rights to the property. The next eldest son, Jacob, took possession and agreed to pay the other heirs their share within a year of 1 March 1813. With Jacob Messner Sr. as surety, Jacob was bound for the sum of $8,000—twice the appraised value of the land (as was the custom).

Jacob died intestate in March 1840 in Mifflin (now Washington) Township. His eldest son John petitioned the Orphans Court to partition his land, about 128 acres adjoining Ludwig Lenker, Samuel Longenbaugh, and others, on which there was a grist mill—“the one half of which mill belongs to the heirs of Ludwig Shott.”

And violà!

There’s the Jacob who owned the adjoining land and 1/2 the grist mill—Jacob Shott, son of Jacob Shott and grandson of Ludwig Shott. Was Ludwig Shott his brother? It seems most likely, but I found no deeds between him and his brother Ludwig. What evidence is there to show that this Ludwig was Jacob’s brother?

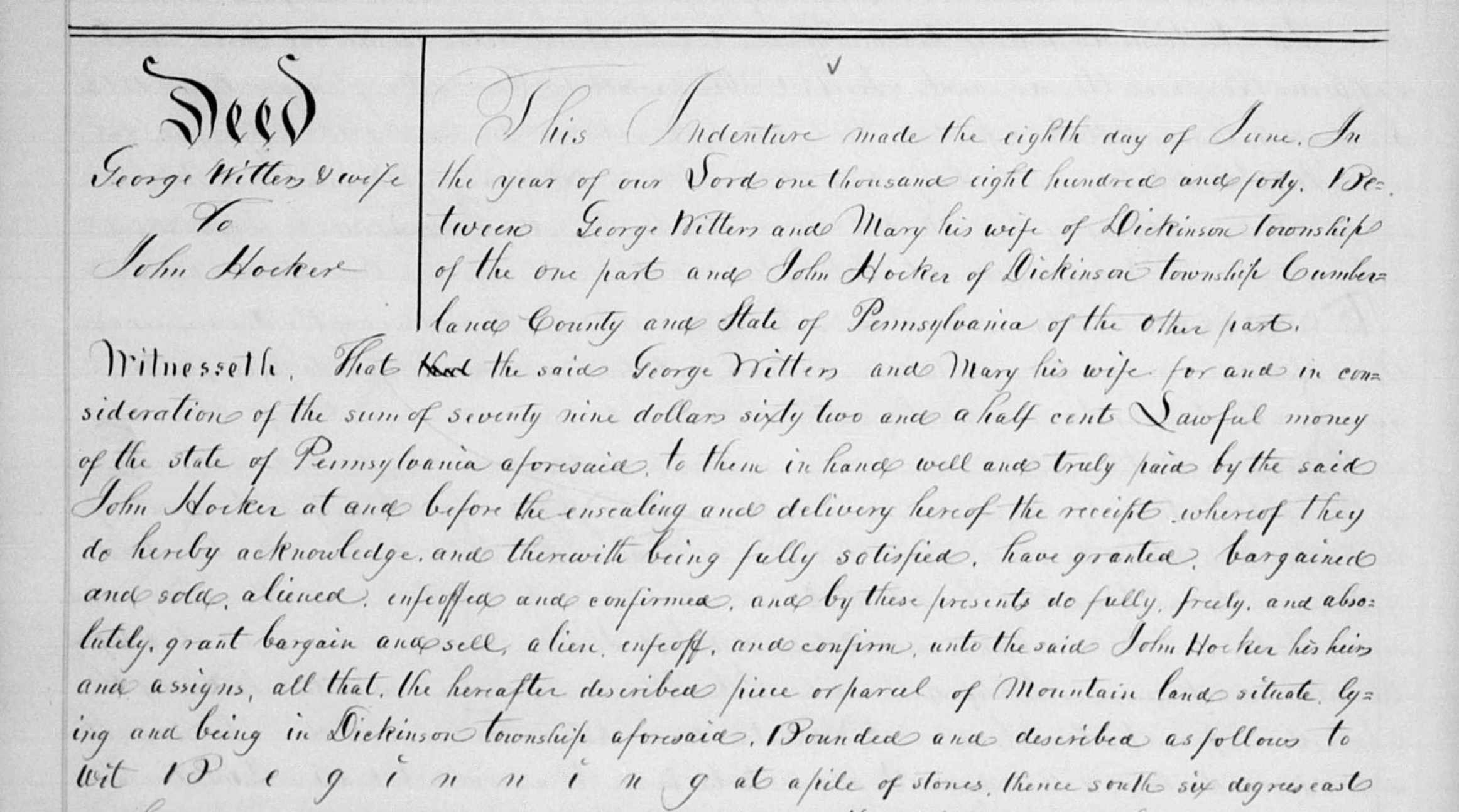

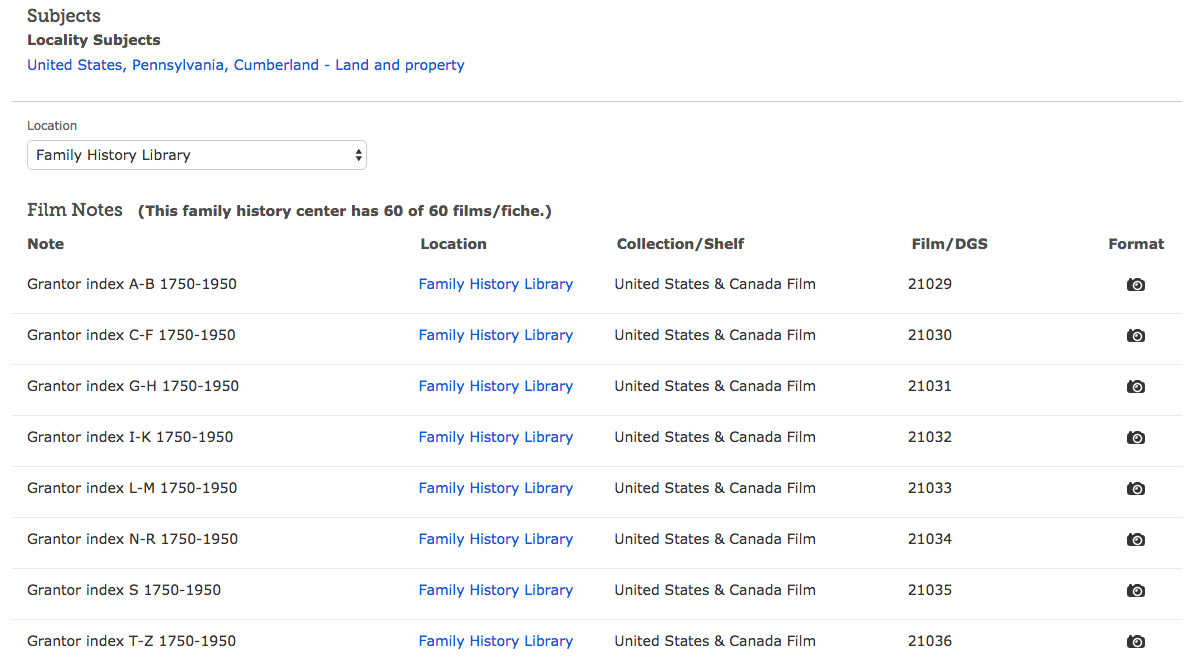

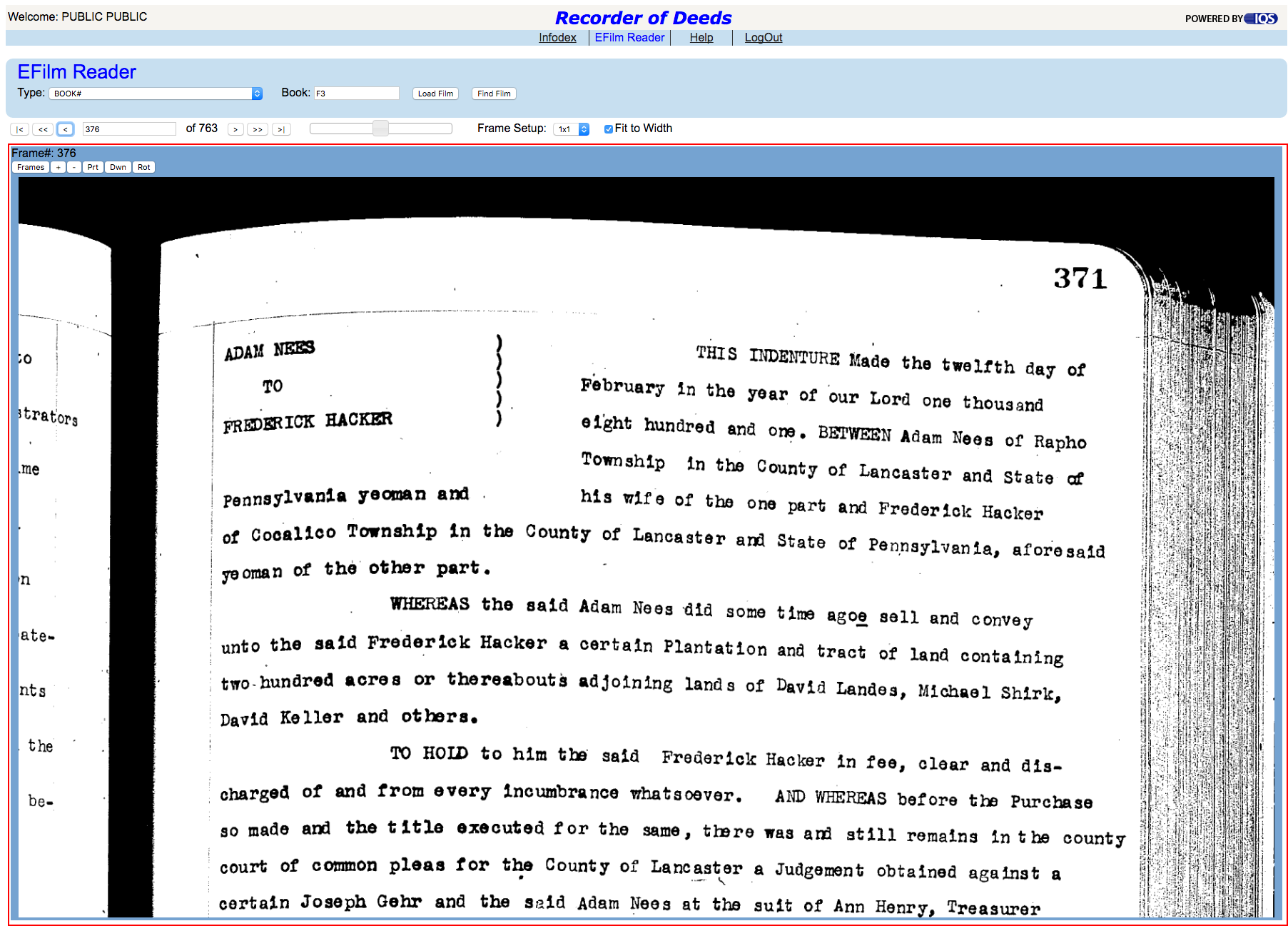

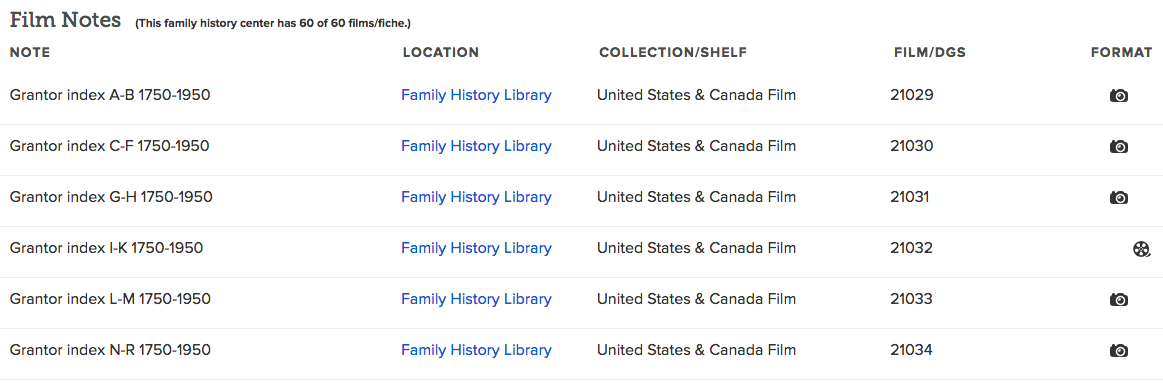

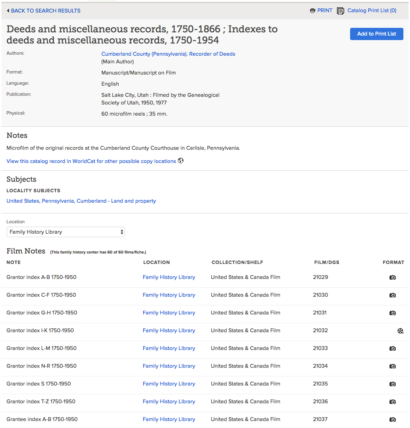

Although there are no deeds directly between Jacob and Ludwig, there are several pertaining to the property that either mention them or in which they are primary actors. The most direct reference, however, was recorded in a deed granting a power of attorney by Jacob’s brother John to their brother Christian.

On 14 November 1818, John Shott appointed his brother Christian as his trustee and guardian to “take recover and receive my said property and monies and the interest thereon accrueing and to dispose thereof for me and my use.” According to the document this included his inheritence from “my brothers Jacob Shott and Ludwig Shott who have taken the real estate of my father Jacob Shott deceased at the valuation of thereof the sum of five hundred and fifty dollars and twenty-five cents.”

Additionally, Jacob Shott and Ludwig Shott sold to Christian Shott on 22 April 1814, 16 acres 80 perches of land adjoining their land, Christian’s other land, and George Minnich, for $231. So, sometime between accepting his father’s land from the Orphans Court on 1 March 1813 and the following spring, Jacob must have formerly sold part of their father’s land to Ludwig—possibly in lieu of or as Ludwig’s share of the inheritance.

An examination of tax records for Upper Paxton Township shows that Jacob and Ludwig had been sharing the land—and paying taxes on it together—since their father’s death. In 1808 Jacob Sr. is crossed out and marked deceased on the tax list and Jacob and Ludwig are listed together with an assessed valuation of $600 and tax of $4.50. They are listed together in the Upper Paxton tax records until 1820 when Jacob is listed in the Mifflin Township records with the grist and saw mill.

Why’d You Do That?

You may ask, why I went through this exercise when the Ludwig who married Margaretha Messner is shown as Jacob Schott’s son in online family trees. Maybe I’m just a curious sort, maybe I’m perverse and untrusting, or maybe I just get confused easily when there are multiple people with the same name—and there are so many of them in my families!

But I often find myself asking (even of myself), “how do you know that?” Especially where there are no citations or source information. When you come upon conflicting information—and it’s likely you will—how will you resolve it?

I could’ve just cited the online family tree and left it at that. But by doing the work, I’ve collected and reviewed documentation that not only verifies the relationship between Ludwig and Jacob, but also starts to fill in the timeline of Ludwig’s life and provide insight into the family. It adds to the knowledge I’ve accumulated regarding this family which in turn will help me to better understand future clues in a much more efficient manner.