How to Use the Pennsylvania Probate Records on FamilySearch

The FamilySearch website includes a collection entitled “Pennsylvania, Probate Records, 1683-1994.” While it isn’t indexed and doesn’t include every county, it’s pretty easy to use once you figure it out.

Probate records can provide quite a bit of family information on your ancestor. A will may tell you how the decedent wanted his property divided and who was to get which pieces. You can get the name of a spouse, children, and associates—as the executor and witnesses were usually people the individual knew and trusted. A will may also point you to other documents. For instance, if the individual ordered that their real estate be sold, you might be able to locate deeds for the sale.

Intestate records may provide the names of the individual’s spouse and children, especially if they were minors and required guardians for their estate or if the decedent’s property needed to be partitioned. In the latter case, you should be able to find deed records for the transfer of ownership to the heir who accepted the property. Later deed transactions may also help you prove family relationships between individuals where there may not be other evidence.

Using this collection is not difficult. Navigating your way through it reminds me a lot of the “old days” of sitting down at a microfilm reader. There are no quick links directly to the information for which you’re looking. So, you’ll need to bounce around until you get to the right page.

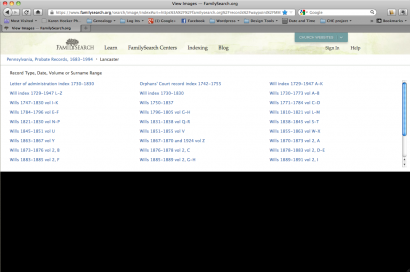

Let’s take a look at the Lancaster County probate records.

The available records for Lancaster County include indexes for Letters of Administrations 1730-1830, Orphans’ Court records 1742-1755, and Wills 1729-1947, and Will Books 1730-1908, volumes 1A through 2R. To find a will, you need to start with Will indexes.

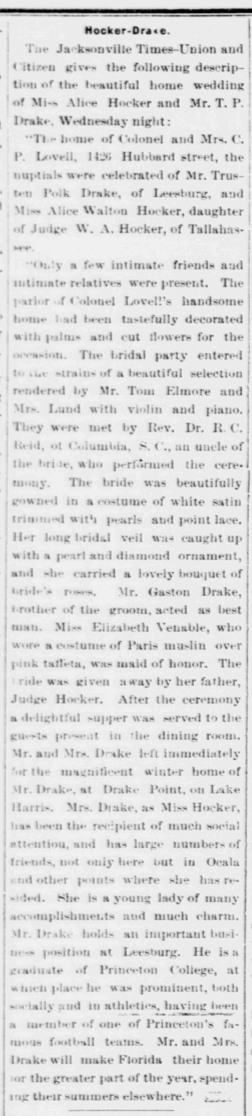

Let’s try to find a will for Henry Huber of Martic Township. I start with “Will Index 1729-1949 A-K.” Clicking on the link pulls up the first frame.

Next I’ll need to try to locate the page(s) that include the Huber surname for first names beginning with the letter “H.” You could scroll page by page, but I usually estimate a starting point and go back/forth from there until I locate the page. I guestimated about image 200 and came up short with the Daub surname and jumped forward until I landed in close proximity to my target, then scrolled image-by-image until I hit the right page. All in all, I’d say it only took a few minutes to find the entry for Henry Huber.

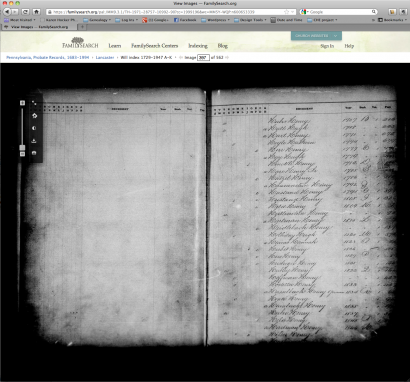

As you can see from the image (click to enlarge), Henry Huber is the first entry. His will was dated 1757 and is located in Will Book B1, page 202. Since the book is online, I can go to find a copy of the will.

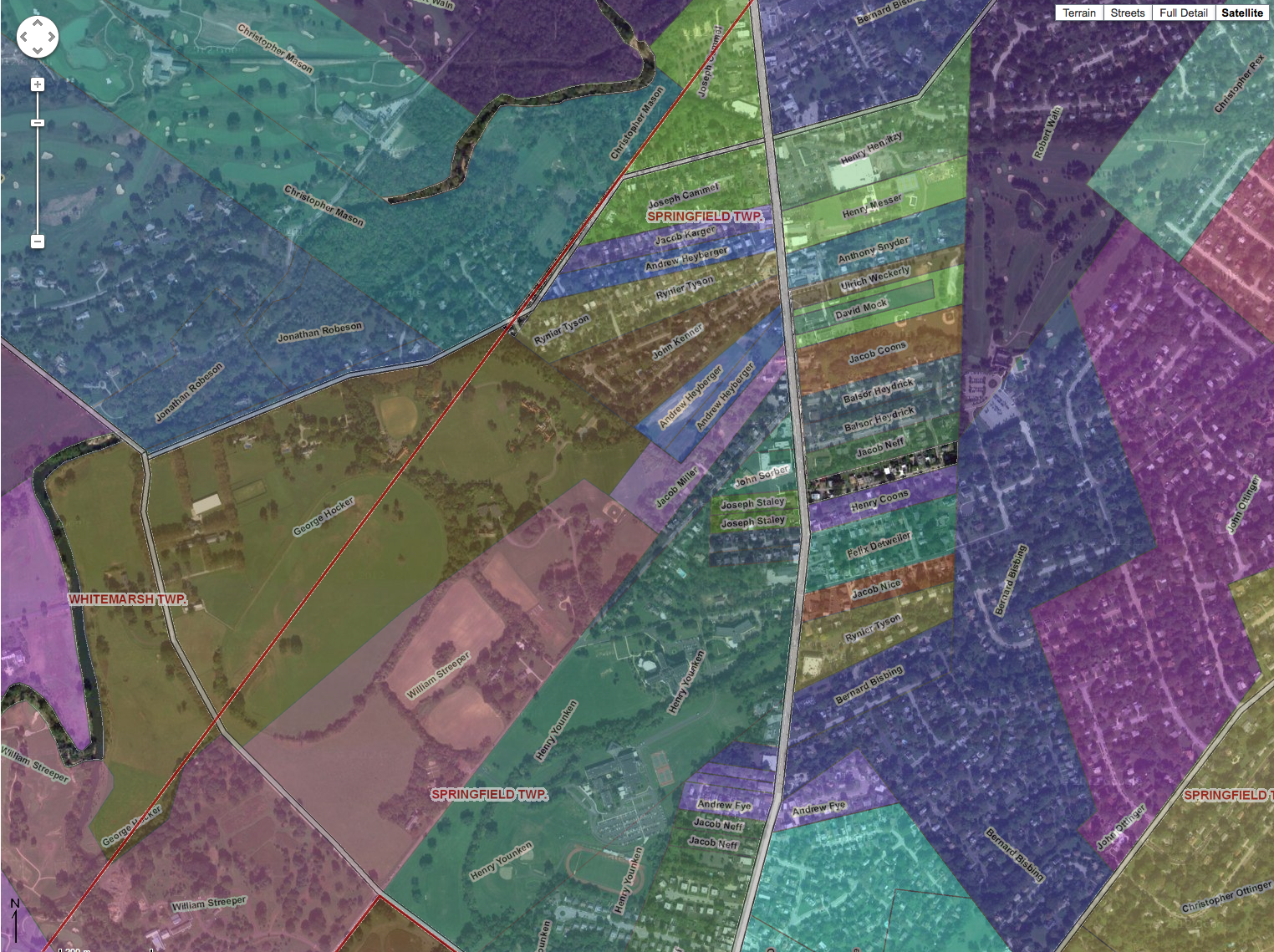

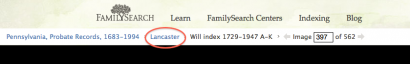

Click on the word “Lancaster” in the breadcrumb trail above the image to open the list of links to available books again.

I clicked on “Wills 1730-1773 vol A-B.” Book B is the second book in this series, so I need to jump forward until I’ve reached it. If there are two books, I go forward about half the number of images and adjust from there. Each image for a book contains a two-page spread, so jumping forward 10 images will jump you ahead 20 pages.

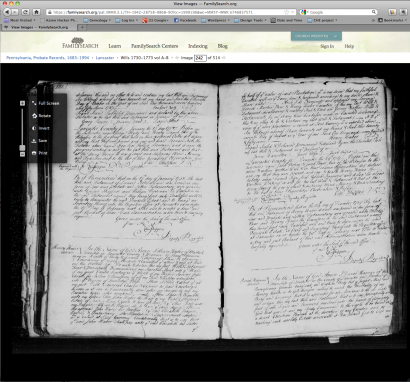

A little back and forth and ta-da! Henry Huber’s 1757 last will and testament.

The various counties in Pennsylvania have different records available to view. For instance, York and Adams counties not only have wills, but also the orphans court records. That means that you can find proceedings for intestates and guardianship petitions. The format of the indexes may also vary from county to county. Instead of a strictly alphabetical and chronological list, some of them use the Russell key indexing system. It uses key letters within the surname to index the names in groups which are then separated out by first name.

If you have Pennsylvania ancestors, give the collection a try and let me know what you find! If you have questions, you can let me know those, too.