5 Reasons to Search Orphan’s Court Records Even If Your Ancestor Left a Will

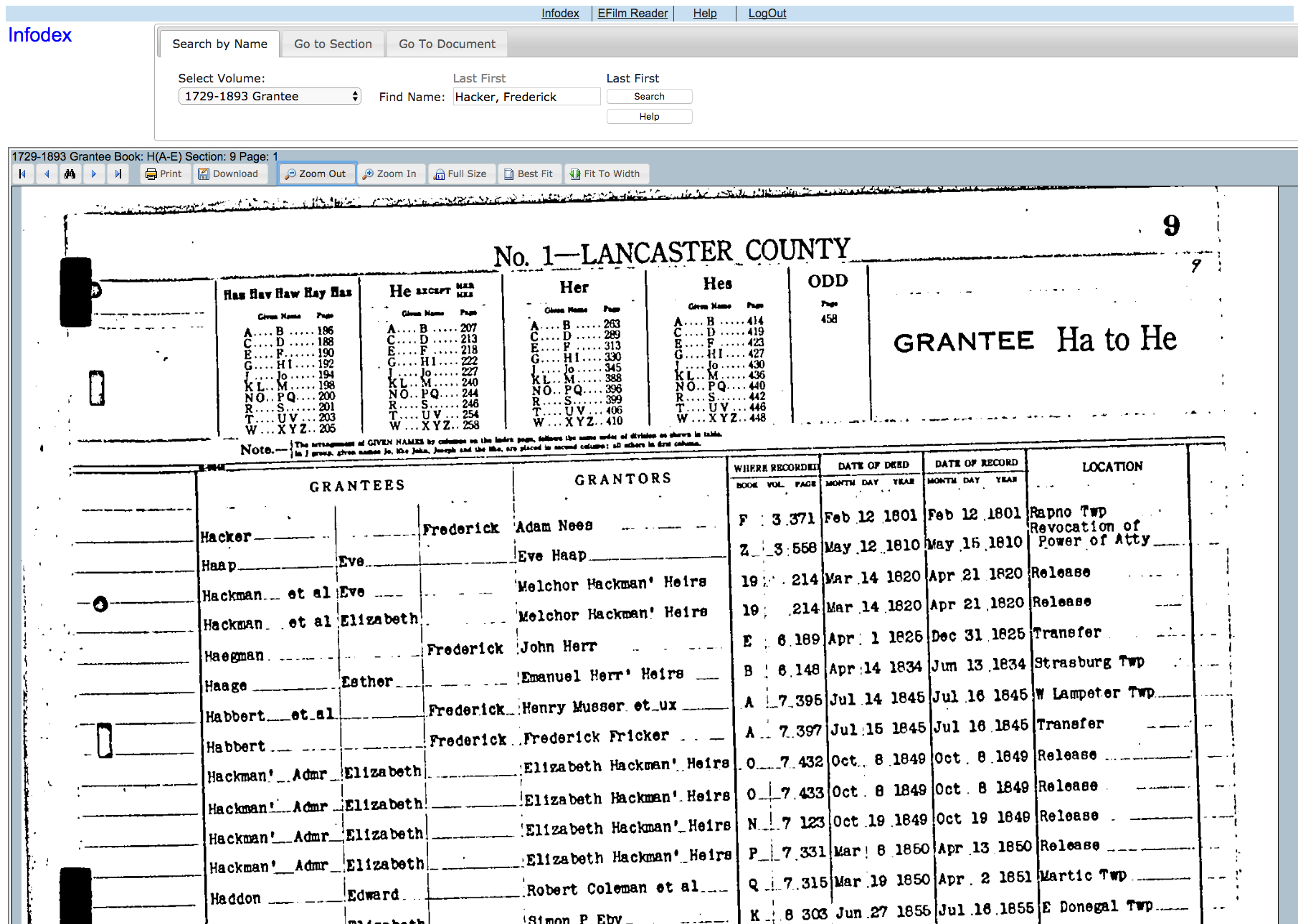

Are you familiar with estate records in Pennsylvania? Yes? Then you know that there are two basic types of probates—testate, those who left a last will & testament, and intestate, those who didn’t.

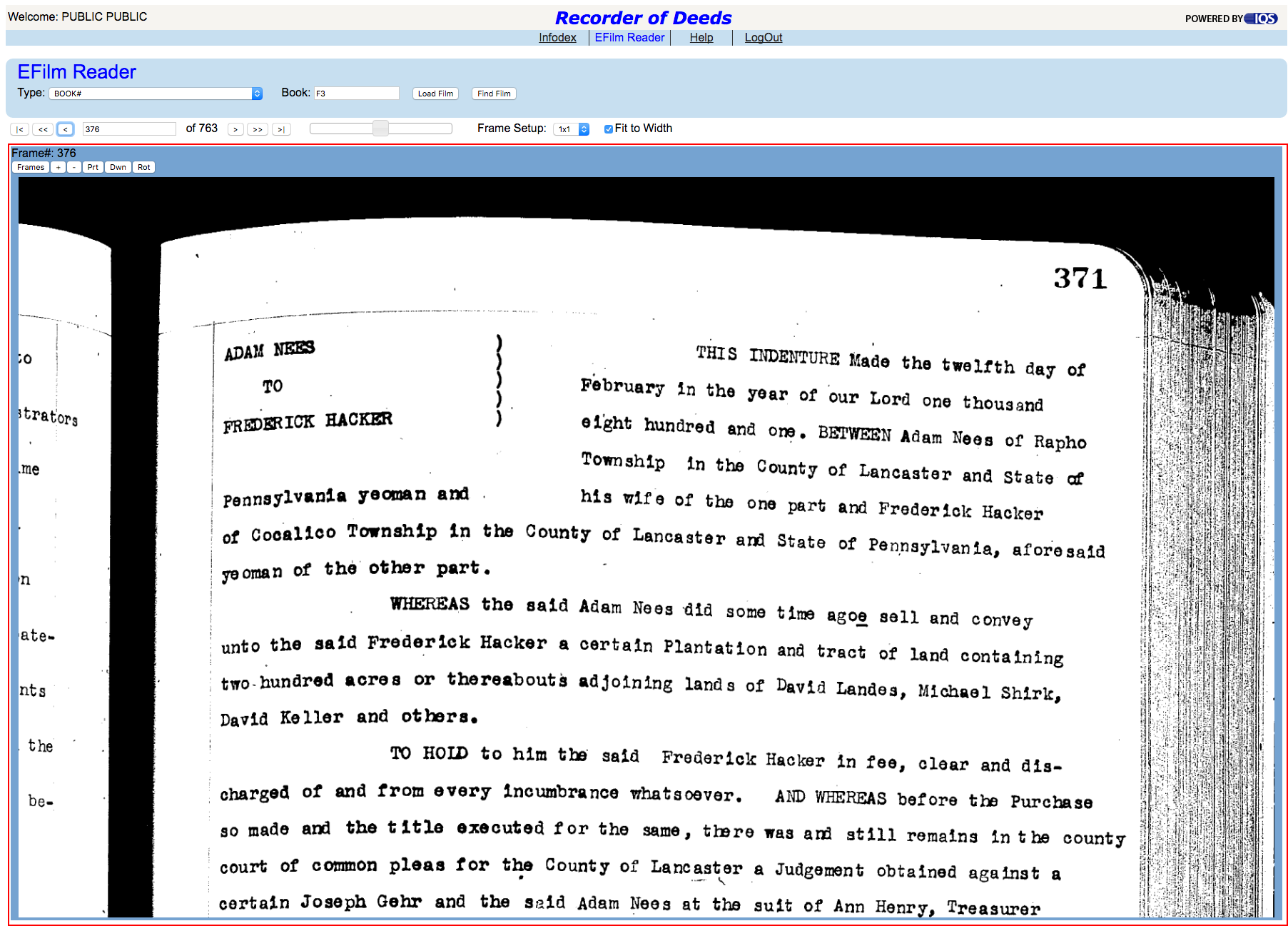

Some counties store all the documents pertaining to a particular estate in one file. This is very helpful to the researcher. Request the probate file—or locate it online—and you’ve got all the pertinent documentation.

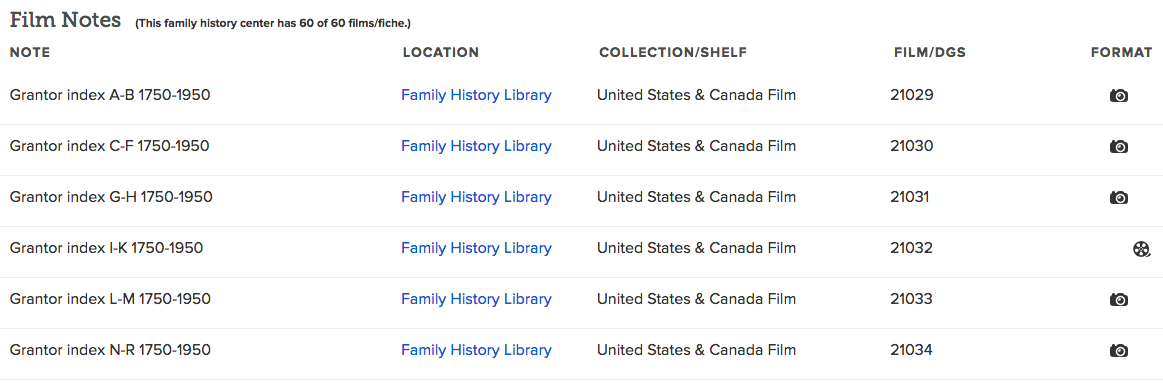

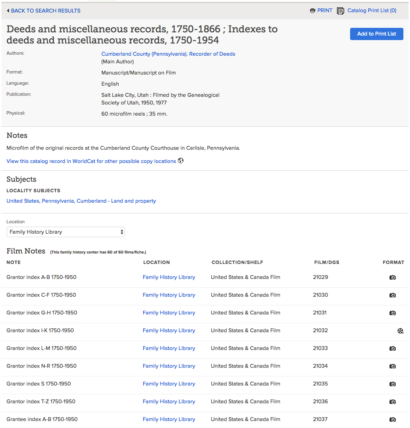

But other counties recorded the documents in separate books. For the testate, the will, inventory, and account were recorded. For the intestate, the administration bond for the administrators, inventory, account, and quite likely Orphan’s Court entries can be found. But to get the documentation, you need to look in multiple locations.

If your ancestor left a will, would you look in the Orphan’s Court records? No? Here are five reasons why you should check the Orphan’s Court records even if your ancestor left a will.

Guardianship

By far the most well known purpose of the Orphan’s Court—as the name implies—was to appoint guardians over the estates of the minor children of the deceased. Anyone under the age of majority was required to have a guardian until they came of age to administer their estate.

Children over the age of fourteen could request a specific person be appointed as their guardian. You will often see young women ask that their husbands be appointed for them. The Court appointed the guardian for those children under the age of fourteen, but those children could request a different guardian once they were fourteen years-old. Those appointed as guardians were usually relatives or persons of significance in the community.

One thing to remember is that the guardian very often was not the custodian of the child. A parent usually maintained physical custody of the child/children until they came of age. The guardian was legally responsible to administer the child’s estate, i.e. their right to property or money from the deceased’s real or personal estate.

Administration Accounts

The executors and administrators of a decedent’s estate were required by law to file an account of their administration of the estate with the Register of Will’s office within one year or as requested by the Court. These accounts were recorded in the Orphan’s Court’s books when those overseeing the estate came into court. Often these entries only mention that the account was approved and name the amount of money to be distributed or debts to be paid.

Sometimes however, the record actually includes the names of those to whom any balance on the estate was paid out and exactly how much money they received. In the case of a testate, the amounts were determined by the last will and testament; in the case of an intestate, the amounts were determined by the inheritance laws. Usually this meant that the balance was divided into equal shares, after the widow’s third was deducted, with the eldest son receiving two shares and the other heirs receiving one share.

Land partition

When an intestate died owning land, the heirs petitioned the court for an inquest of partition. The court would appoint men to assess and value the property and determine whether or not it could be divided among the heirs without “prejudice to or spoiling the whole.”

In most cases, the land could not be divided, and thus the court would grant the land to the heir who accepted it at its valuation and agreed to pay the other heirs. In the event that none of the heirs took the land, the court often granted a writ of sale, allowing the administrators to sell the land. The proceeds would then be distributed among the heirs.

If your ancestor left a will, but died owning land which had not been accounted for in the document, the process for determining who would get that property was the same as if there were no will. The heirs went into the Orphan’s Court and petitioned for an inquest of partition for that specific tract of land. Once the inquest and valuation were returned to the Court, it would either assign ownership or issue a writ of sale.

No named executor

In most cases, the will named those the decedent choose as executor to administer their estate. However, I have seen cases where no executor was named in the will. I have also seen cases where the will was not accepted by the Register of Wills. In those cases, the estate was treated as if the decedent died intestate and administrators were appointed, an administration bond issued, and letters granted to them even though there was a will.

Estate inventory

And finally, the estate inventory. In most counties the Register recorded the estate inventory in its own book. However, I have on occasion seen inventories recorded in Orphan’s Court books. While I believe that they are most often those of intestates, I can not vouch 100% that that is always the case. It’s not a common occurrence, but if you’re looking anyway, you might get lucky.

So, there you have it. Five reasons why you might want to check out the Orphan’s Court records, even if your ancestor left a will.

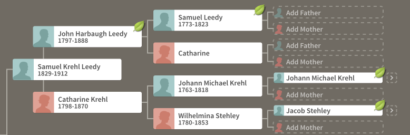

And for some ancestors, this is what has happened. Ancestry’s shaking leafs have shown me records that I don’t have. And helped me learn more about them. For the most part, however, it’s shown me records that I already have or would have easily located by doing a basic search for that ancestor.

And for some ancestors, this is what has happened. Ancestry’s shaking leafs have shown me records that I don’t have. And helped me learn more about them. For the most part, however, it’s shown me records that I already have or would have easily located by doing a basic search for that ancestor.