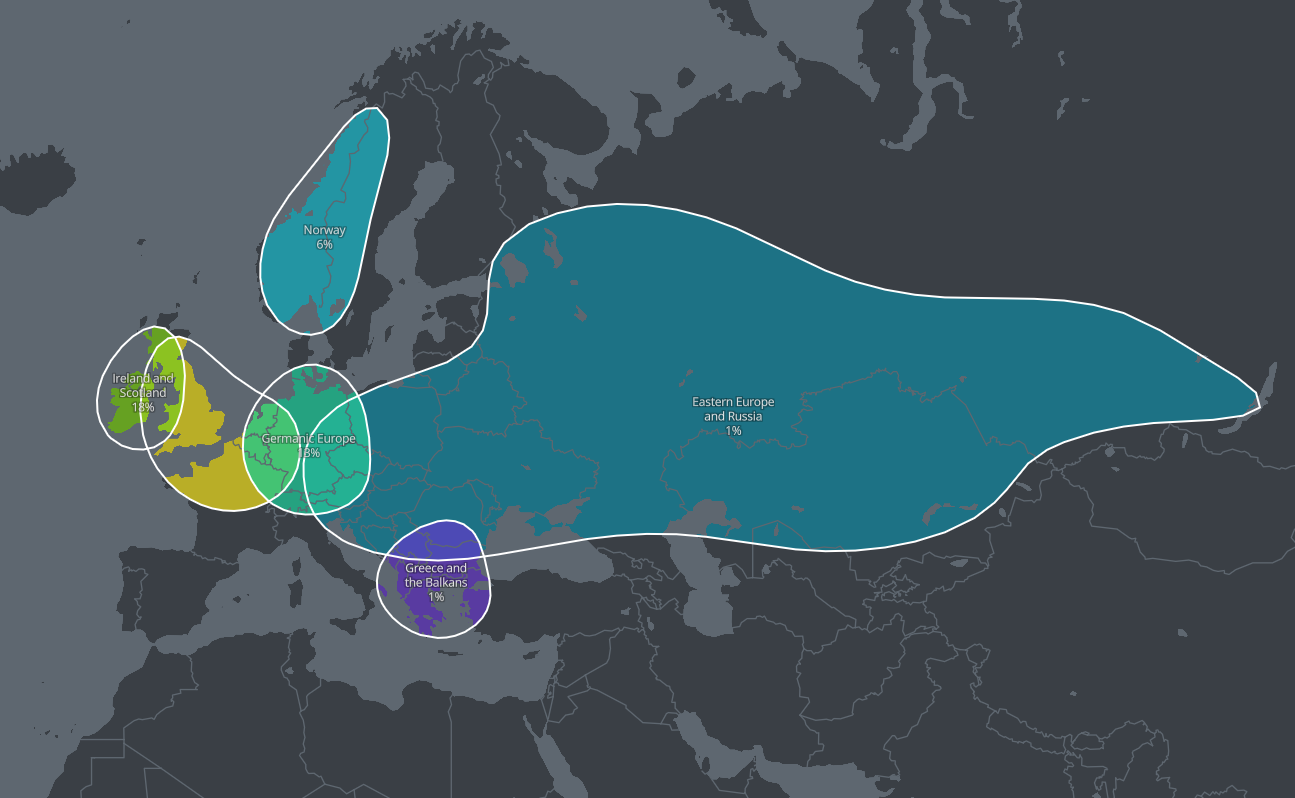

I’ve been using AncestryDNA for more than a year now. Like most anything, there are good points and bad points, things I like and things I don’t like. Here are my five top tips to help you turn my top frustrations into your opportunities to get the most out of your AncestryDNA test results.

1. Add a family tree

What’s the number one thing you can do to maximize the benefit of taking an AncestryDNA test? Add or build a family tree on Ancestry. If you want to make connections to your DNA matches, they’ll need something to connect to.

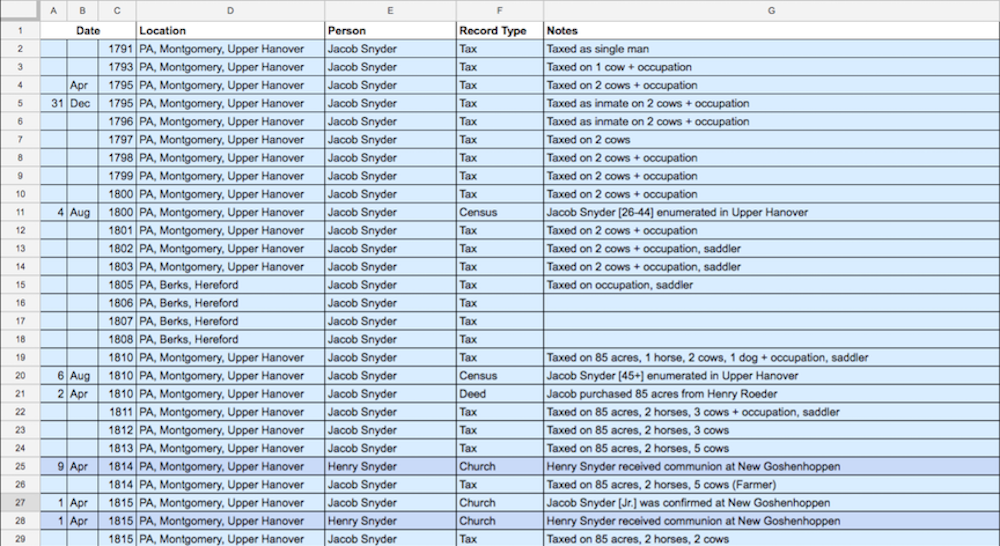

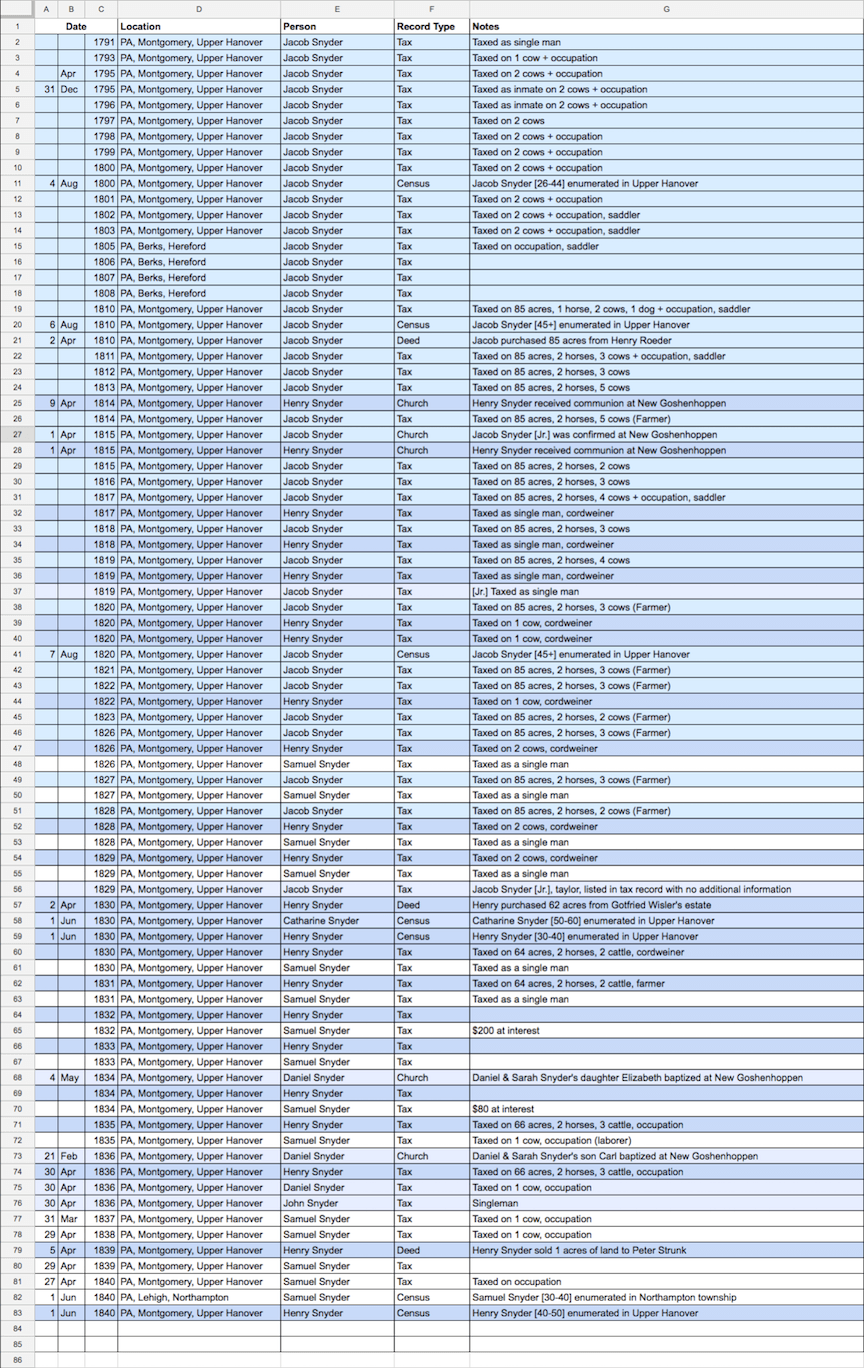

You don’t need to be able to trace your ancestors back to the original immigrant. Add yourself, your parents, your grandparents and so on as far back as you can. If you can only get a couple of generations, that’s okay. If you can get back to those born before 1940, that’s even better. (See tip #3 for why this is important.)

And, please, add dates and places. Sometimes, when surnames don’t click, places can point a match to the appropriate line in your respective trees to research further.

2. Connect your tree to your DNA test

If you don’t connect your tree to your test, your matches will see the “No family tree” image beside your information, even if you have a tree. They won’t know you have a tree unless they click to view the match. And if it says “no family tree” they may not think they have any reason to view your match. So, please link your DNA test to your tree.

Update: Ancestry has changed this up a bit. They now provide multiple status designations for tree: # People to show there is a tree, Unlinked Tree for trees not linked to the DNA test, a lock icon to show the tree is private, a leaf to show there’s a common ancestor, No Trees, and Tree Unavailable.

Attach the DNA test to you. If you manage another test, attach that test to the correct person in your tree—or their tree if you’ve set up a separate one for them. Don’t make your matches guess whether or not the testee matches the home person in the tree.

I can’t tell you how many matches I’ve looked at where the test belongs to a male and the person shown in the tree is female, or vice versa. My reaction is always the same. Next match.

3. Trace collateral lines

Since the point of taking a DNA test is to connect with cousins (aka matches), building out your collateral lines—aunts, uncles, etc.—as far as possible makes it easier for Ancestry (in the form of Shared Ancestry Hints, aka shaky leaves) and your matches to find your most recent common ancestor. I’ve found it not only increases the number of Shared Ancestry Hints, but I can also recognize names more easily in a match’s tree, even if their tree doesn’t go back far enough to connect to our common ancestor.

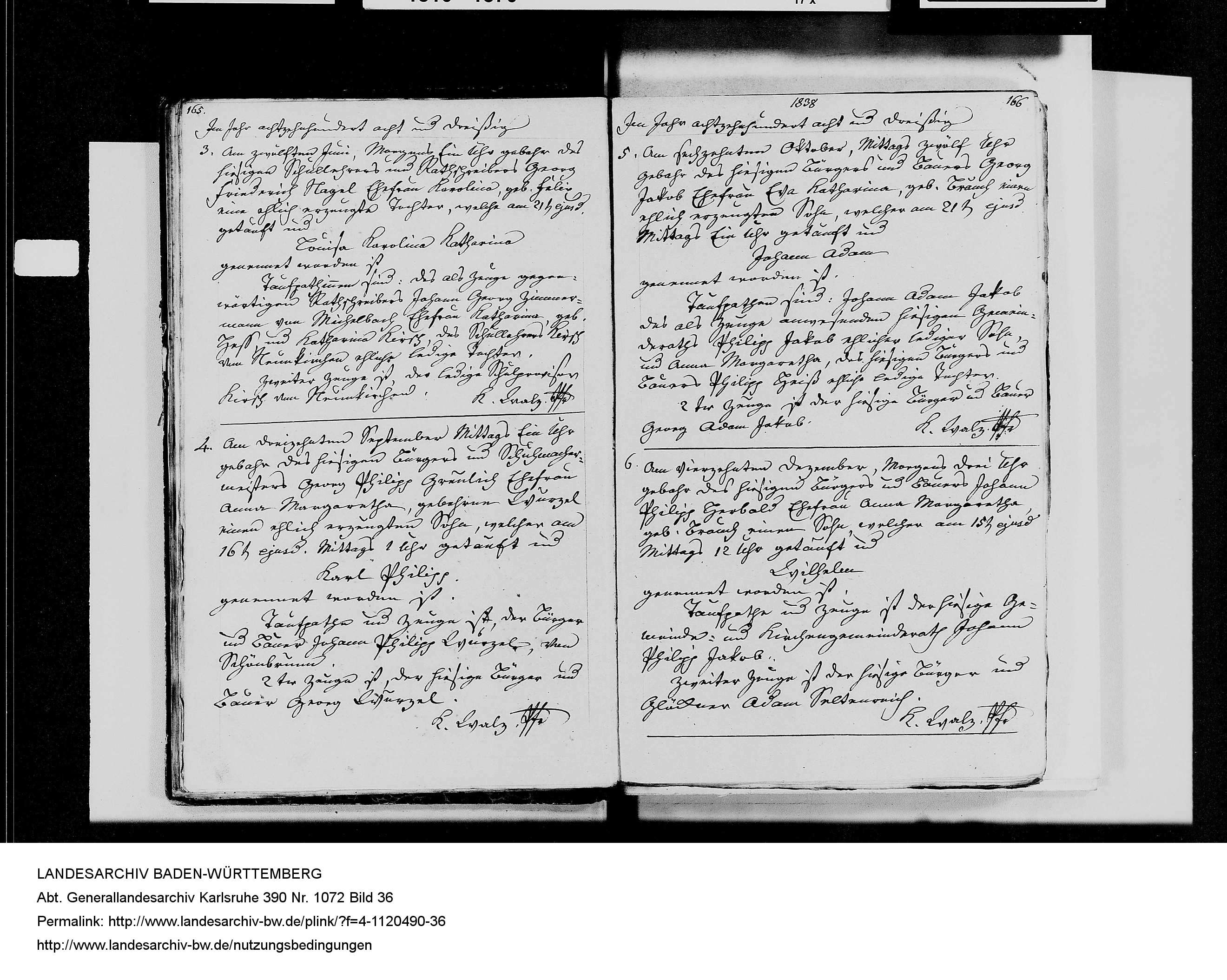

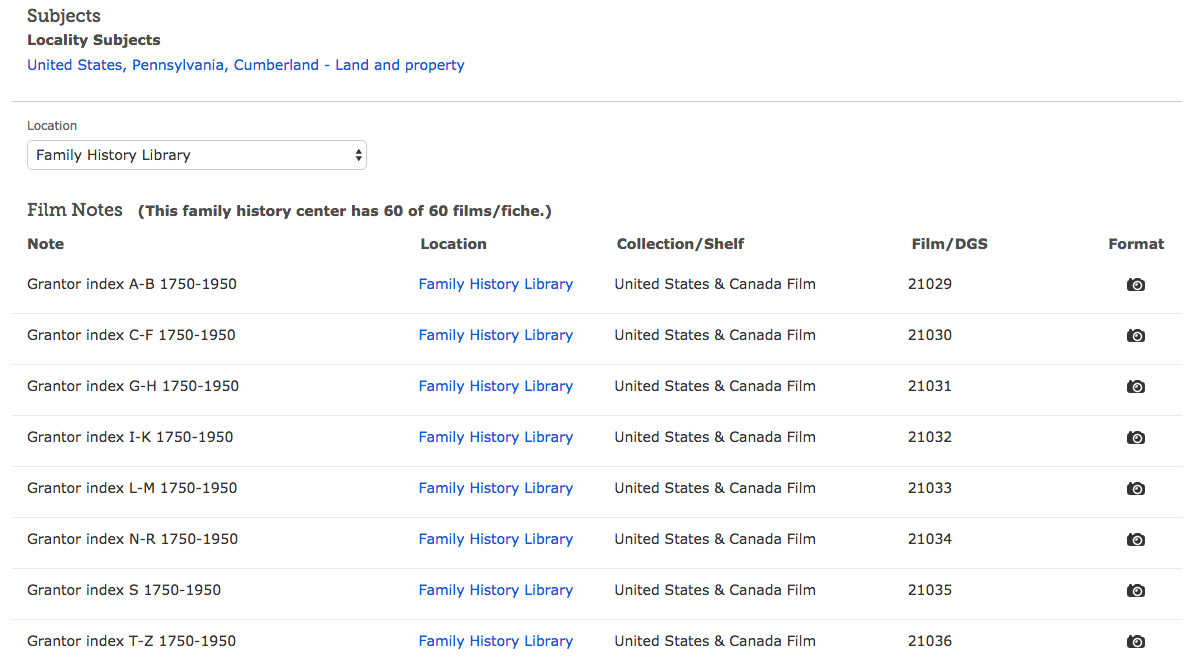

In most cases I can build out collateral lines down to those born before the 1940 census. I can often take them further, especially in Pennsylvanian lines, if I luck out and find military compensation files, pre-1964 death certificates, obituaries, and/or Find A Grave entries. If I can datamine online directories and Facebook, I can often flesh out a tree to the present.

4. Make your tree public

A lot of people make their trees private. I can understand that; I have a private tree that I use for my most of my research. I also have a public tree that’s tied to my DNA test. If you want to get DNA Circles, your tree will need to be public.

What’s the benefit of DNA circles? Besides easily finding testers who descend from a specific ancestor, you will also find testers who you do not match, but who match other descendants of that ancestor. For instance, there are six members of the Philip Hoover and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover DNA circles. I only match three of the members. One of these matches shares DNA with all the other Circle members. I can “View Relationship” with each member to see how we’re related. Even if we do not share DNA.

The largest Circle of which I’m a member is the George M. Walker DNA Circle. It has 28 members. Considering he had 26 children with two wives, this is hardly a surprise. These matches—and non-matches—can help me build out the descendants in his family tree.

You can also get “New Ancestor Discoveries” if your tree is public. If two or more of your matches share a common ancestor in their tree and share DNA with you and each other, you’ll see their common ancestor as a New Ancestor Discovery. You may or may not actually be related to them, however. Several of my matches are descended from Jeremiah Rupert (1852-1924) and Abby Ann Heasley (1857-1908). I’ve traced a couple of these matches back to Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas. The rest I’m unsure about. So far, I’ve found no direct connection between the Rupert family and any of my direct ancestors.

5. Download your DNA results

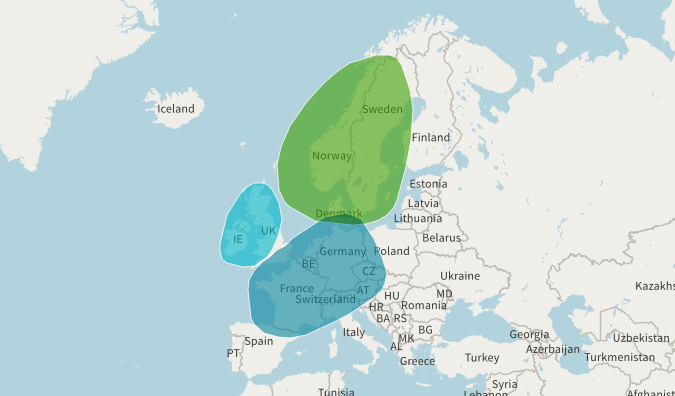

And the final tip, download your DNA results. Why? So you can upload it to :

- GEDmatch

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage

- LivingDNA

Each of these sites will provide you will additional DNA matches—for free! Granted AncestryDNA has the largest database, but it’s not everyone’s first choice. By uploading to these sites, you’ll be able to include those potential cousins in your research, too. You never know when you might find the cousin who has the family Bible or photos.

On GEDmatch and FTDNA (for a small fee) you’ll also get access to additional tools. Both of these sites will not only list your DNA matches, but will show you where you match on the chromosome(s). This allows you to use more sophisticated techniques—like triangulation—to determine which segments of your chromosomes map to which ancestors.

This creates a more definitive identification of a shared ancestor between you and specific matches than Ancestry’s Shared Ancestor Hints—which is based more on the matches in your respective trees than DNA shared between you.

So, these are my top five tips. I’m sure there are others. What do you do to get the most out of your AncestryDNA results?