An issue recently came up in a Facebook group that I belong to for my Weidman surname. A fellow family researcher had found information that connected our Weidmans to President James Buchanan.

I’ve never been terribly interested in making connections to famous persons in my family research. My ancestors were all farmers and laborers with a few shoemakers, innkeepers, tailors and such thrown in the mix. And I’m good with that.

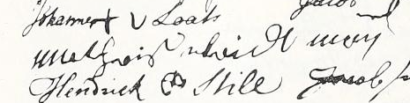

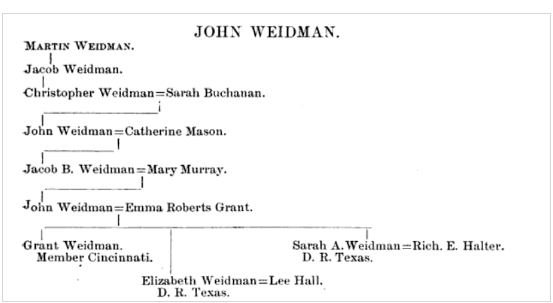

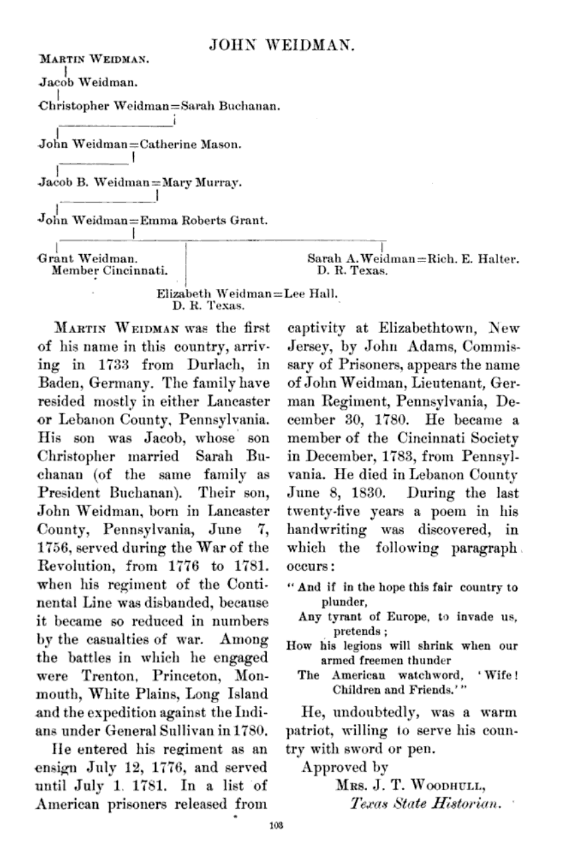

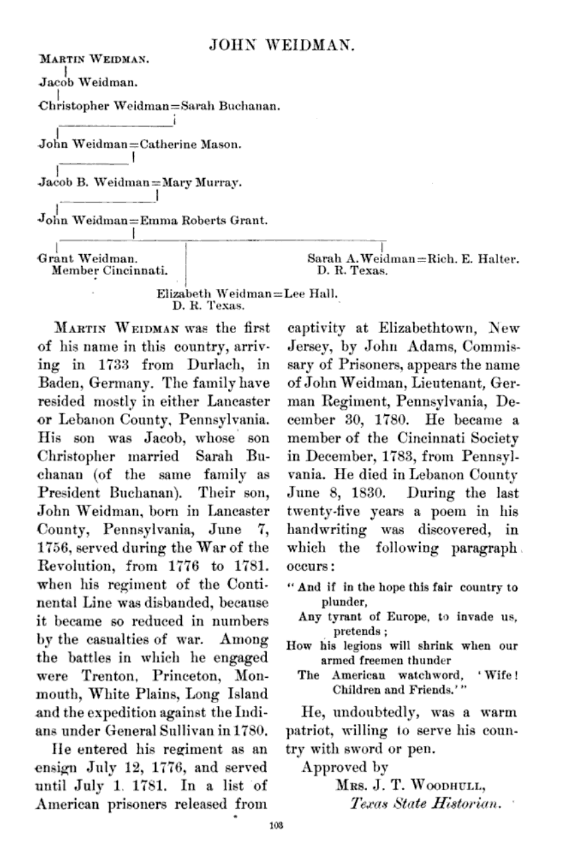

Here is the page of information relating to the issue in question.

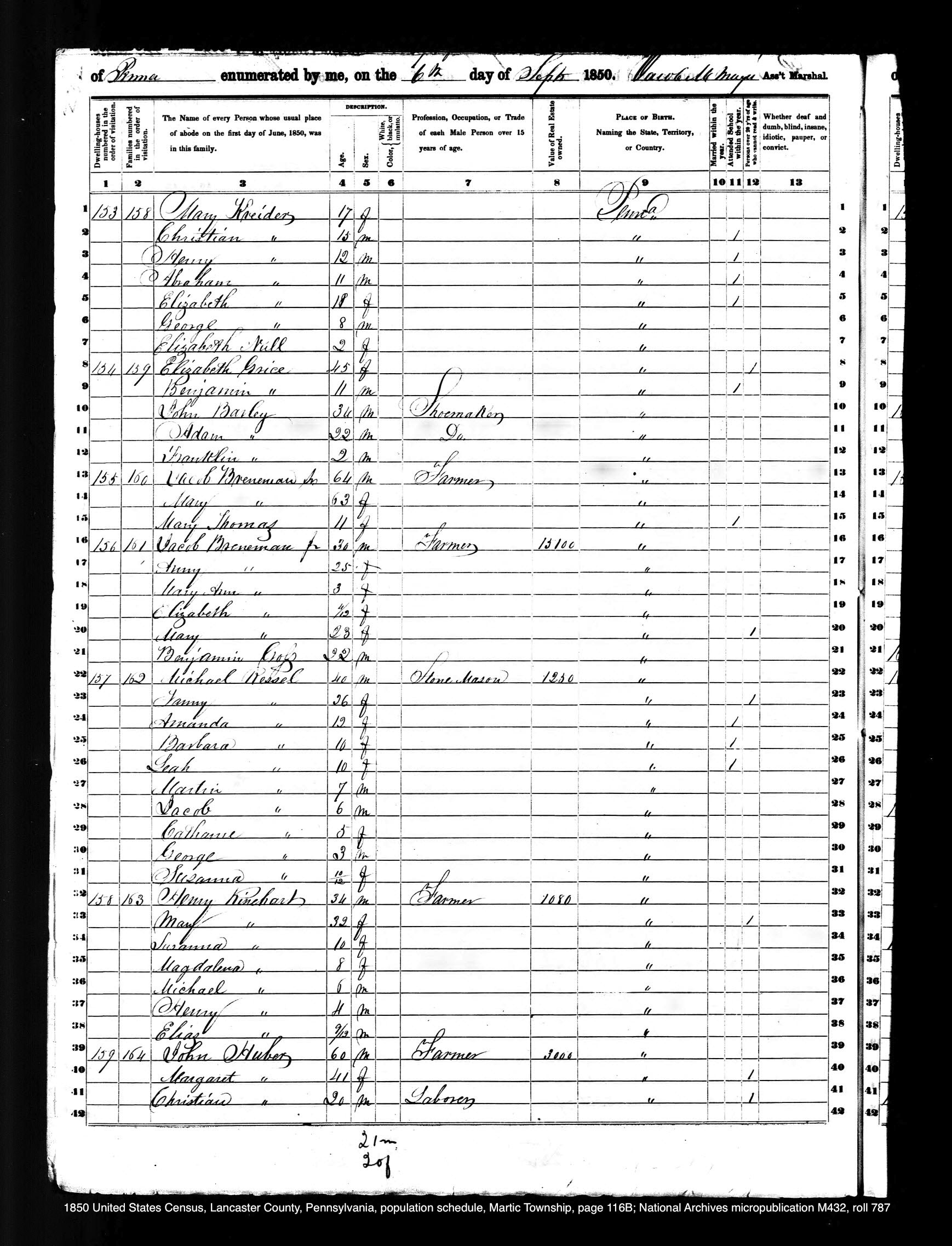

Reading the information, I was nodding. Yes, Martin Weidman had a son named Jacob. True, Jacob had a son named Christopher. I don’t have much information on Christopher, so this was looking like new data to add to the database. Christopher and his wife had a son named John born in 1756 who fought in the Revolutionary War…

Wait! What?

Right away I knew this information couldn’t be correct. Jacob Weidman, son of Martin and Anna Margaretha (Still) Weidman, was born 12 March 1736. There’s no way that Jacob had a grandson born when he was twenty years-old. No way.

Do the math. It just doesn’t add up.

Jacob’s son Johannes Fridrich was born 17 August 1764, so he wasn’t the John referred to in the article. What about Jacob’s older brother Christopher? Did he have a son named John? Maybe Jacob was incorrectly added to the pedigree.

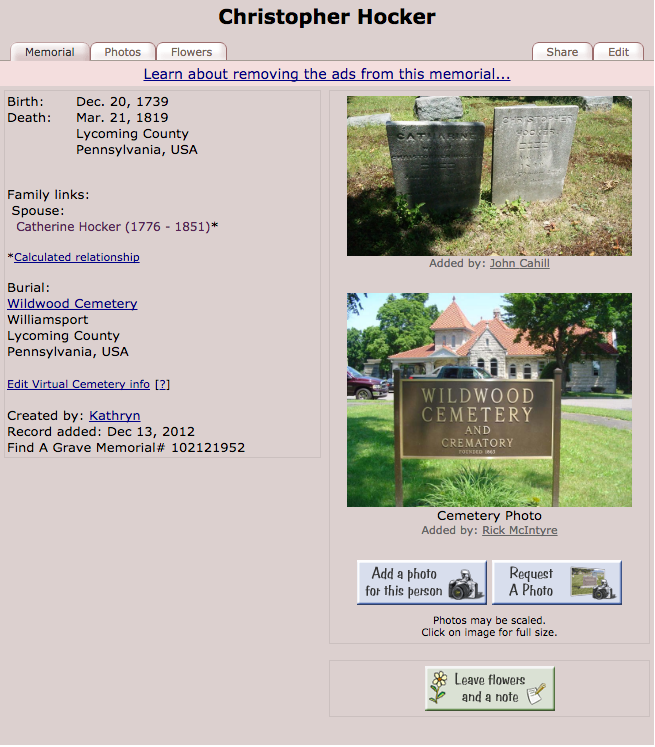

Christopher Weidman

Reviewing my information I found that, yes, Christopher and his wife Anna Maria did, in fact, have a son named John. I didn’t actually have birth information for him, but a birth in 1756 was consistent with what I knew about his siblings.

What wasn’t consistent was a mother named Sarah Buchanan. Where was that coming from? Was I mistaken in the name of Christopher’s wife?

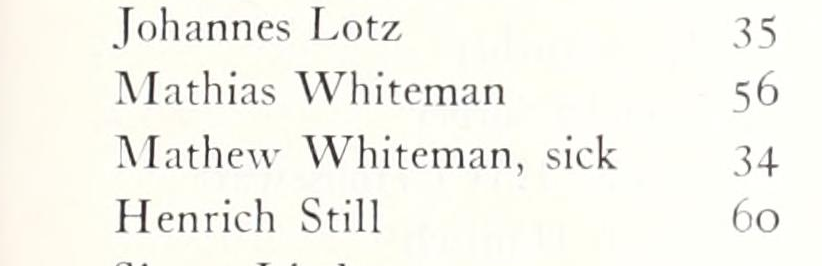

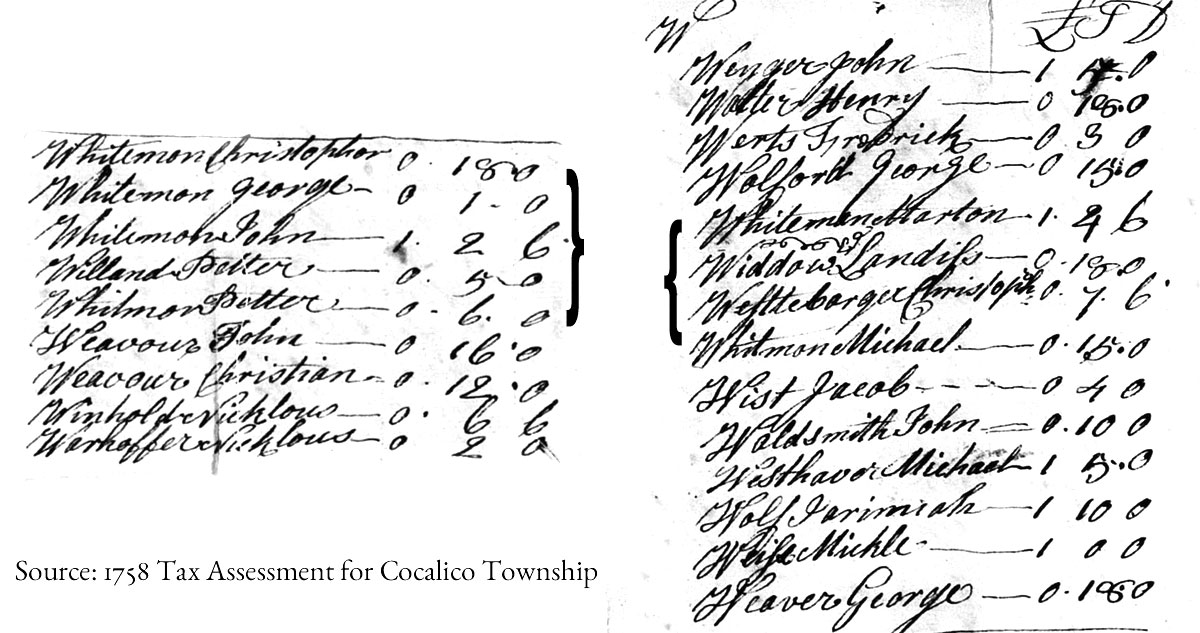

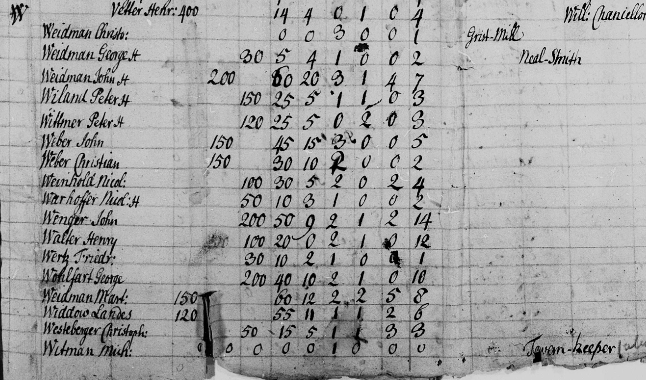

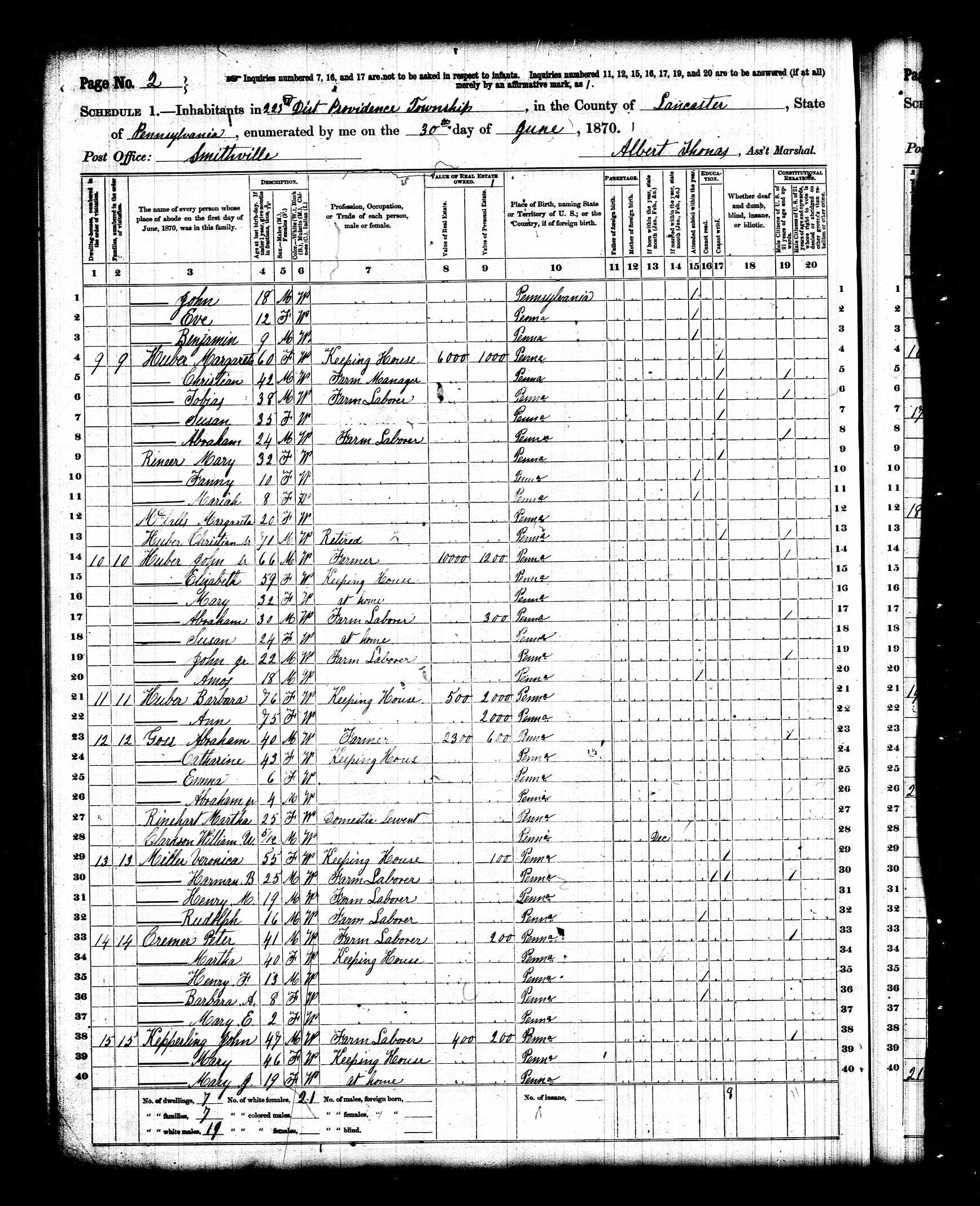

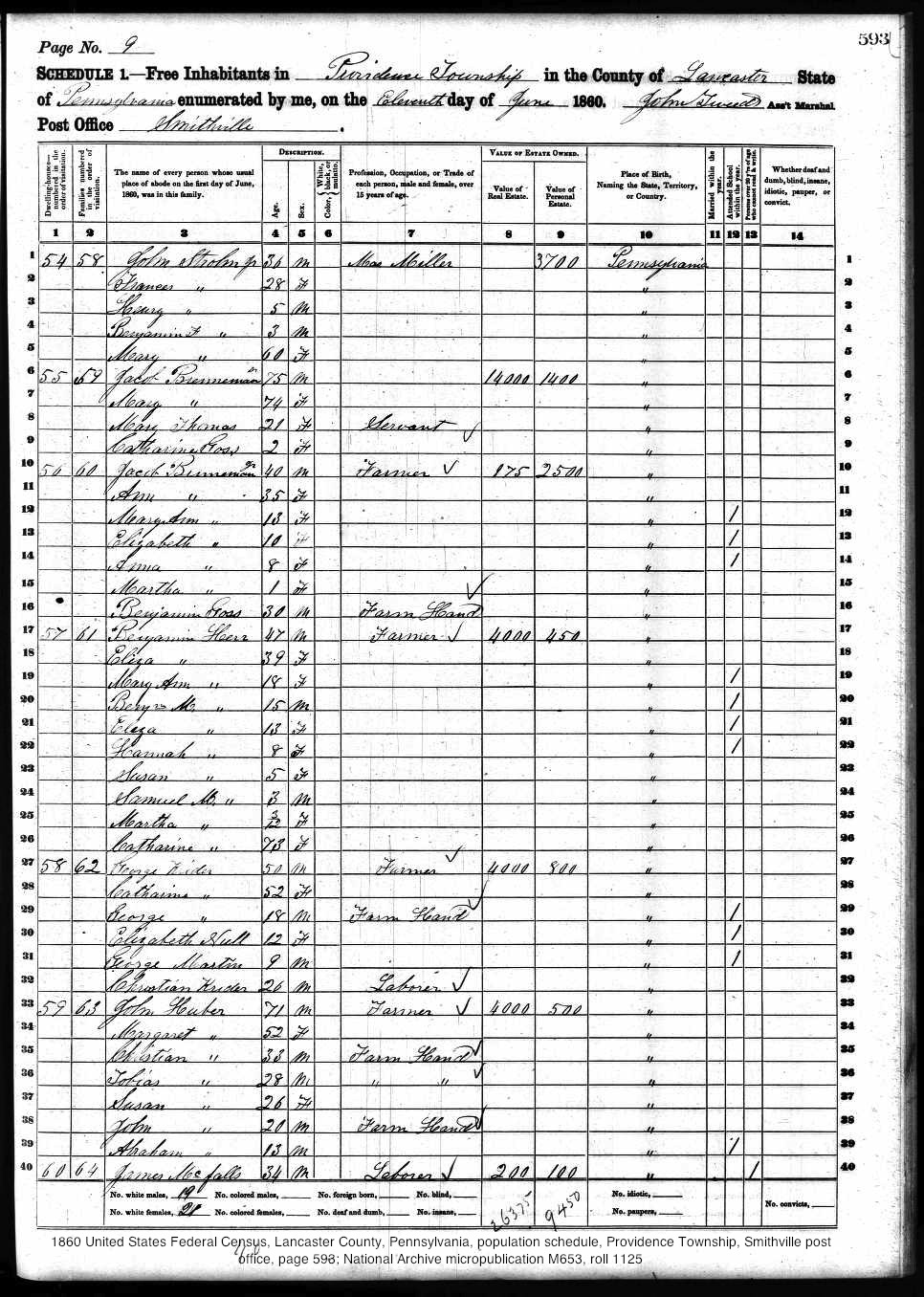

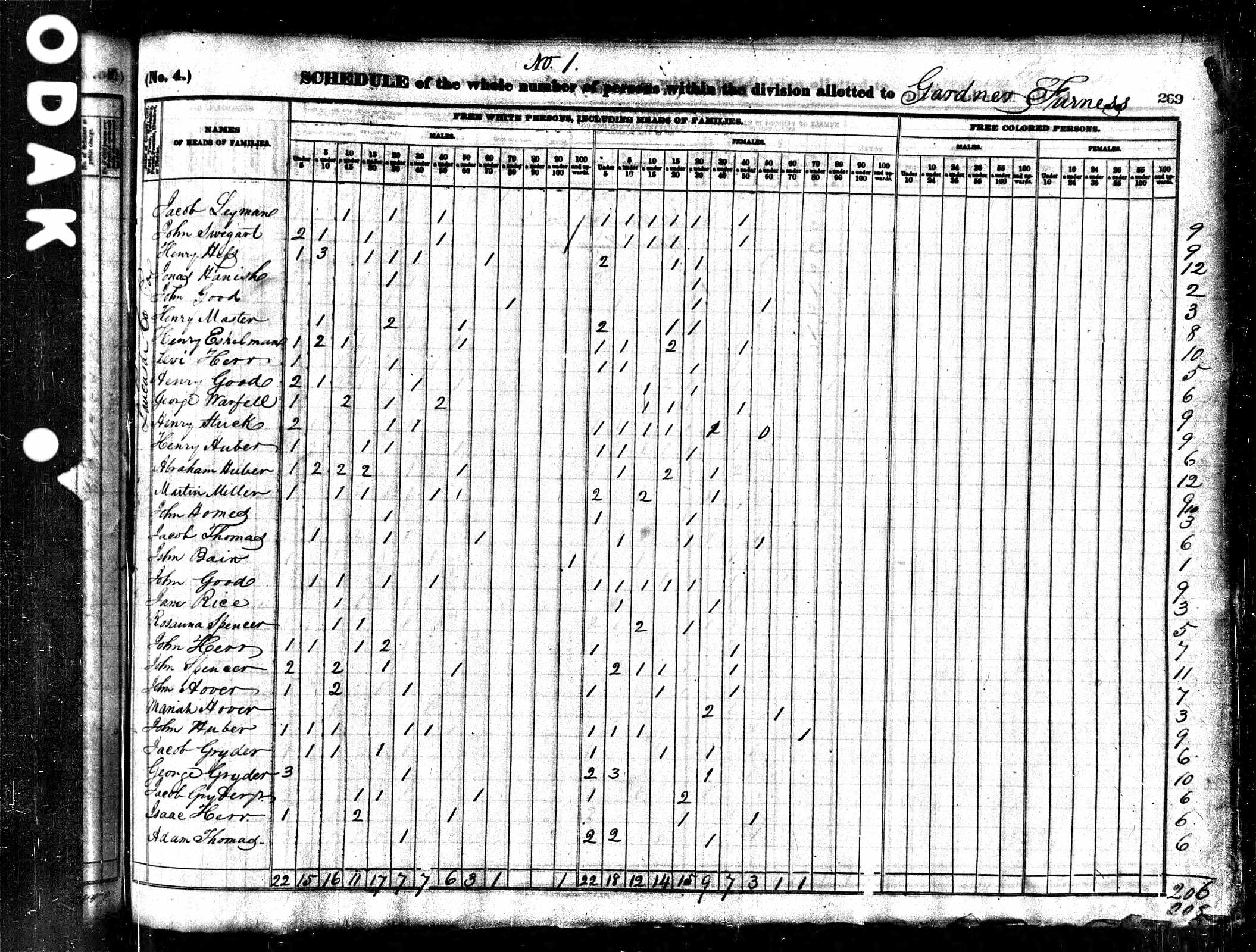

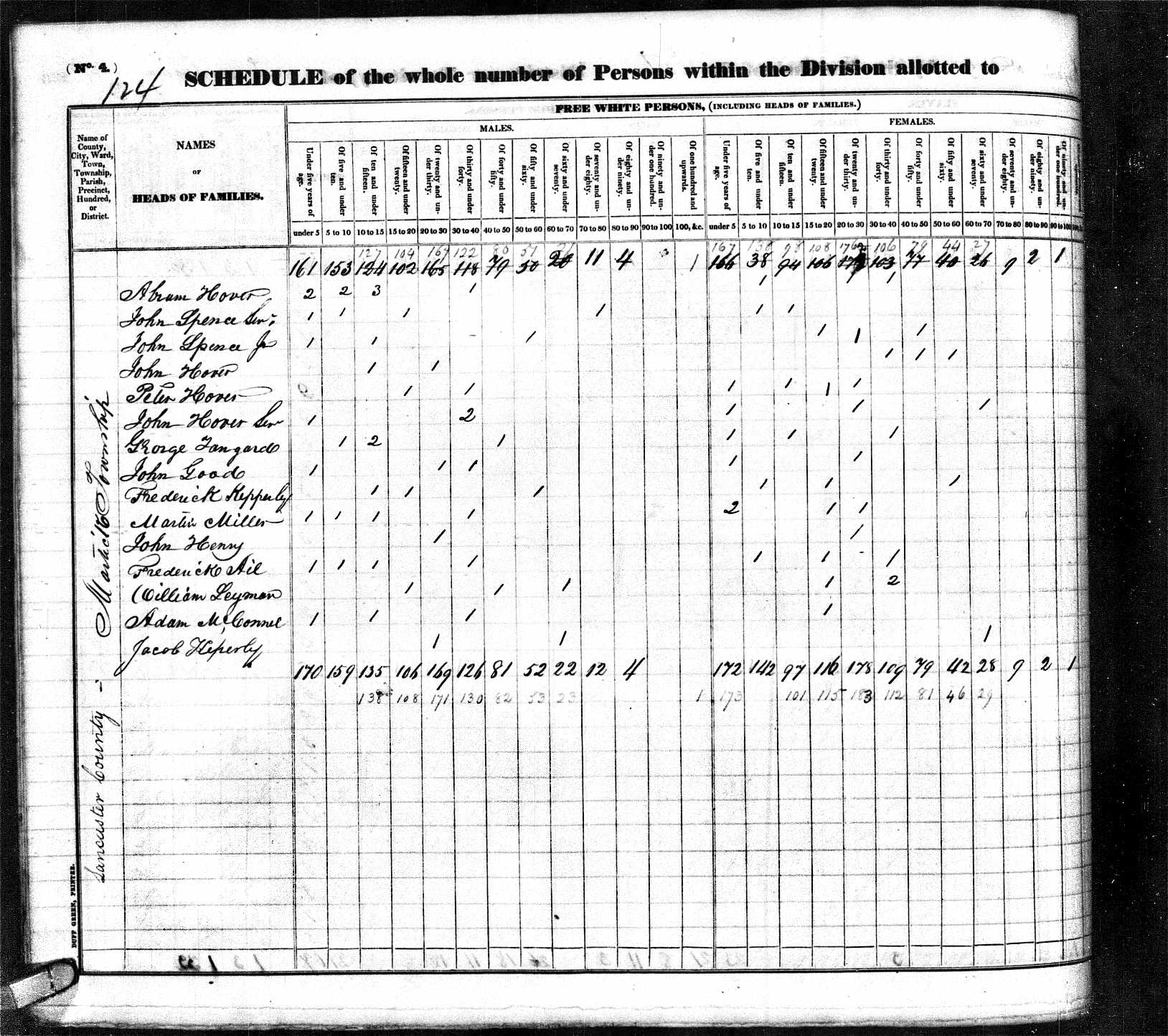

I went back through the information I had on Christopher. He was born 7 March 1724 in Gräben, Baden-Durlach. He came to Pennsylvania with his parents and grandparents, arriving in Philadelphia on 27 August 1733. After their arrival, Christopher’s family settled in what—at the time—was often referred to in official documents as Cocalico Township in Lancaster County, though today it’s Clay Township.

I found a record of a marriage between “Christopher Wittman” and “Mary Adams” at Muddy Creek Lutheran Church in Cocalico Township on 20 June 1748. Christopher would have been twenty-four years old in 1748.

In his last will and testament, written 20 March 1777, Christopher named his wife Anna Maria. I have baptismal and communion records at Emanuel Lutheran and Reiher’s Reformed churches naming Christopher and his wife Anna Maria from 1769 through 1777. Deeds from his estate settlement, however, name his wife as Barbara. He married Barbara (Kissinger) Bücher, widow of Christian Brücher, 8 November 1785. So, his wife Anna Maria died sometime between 6 July 1777 and 8 November 1785.

I found no evidence that Christopher had a wife named Sarah. Unfortunately, I can’t positively rule it out either.

Mary Adams

Part of the problem with Weidman research is the lack of consistency of the spelling of the surname in historical records. Add in another unrelated family named Witman who also lived in the same general location and you’ve got a problem. Add a contemporary of Christopher Weidman named Christopher Witman… well I’m sure you see where I’m going. Since some records list known Weidman family members with the “Witman” spelling, it’s a pretty tangled web to unweave sometimes.

Since I didn’t find any records naming Christopher’s wife between the marriage in 1748 and 1769 baptismal records, I decided to research Mary Adams. Who was she? And can I document connections between her family and the Weidmans?

Christopher and his wife Anna Maria sponsored children of George and Catharina (Weidman) Wächter, Martin and Anna Catharina (Enck) Laber, George and Margaretha (Weidman) Illig, Michael and Susanna (___) Rogh (or Roth), and Christopher and Catharina (Weidman) Stichel. Anna Maria also sponsored a daughter of Jacob and Anna Maria (___) Enck. No obvious signs of a sibling of “Mary Adams” there.

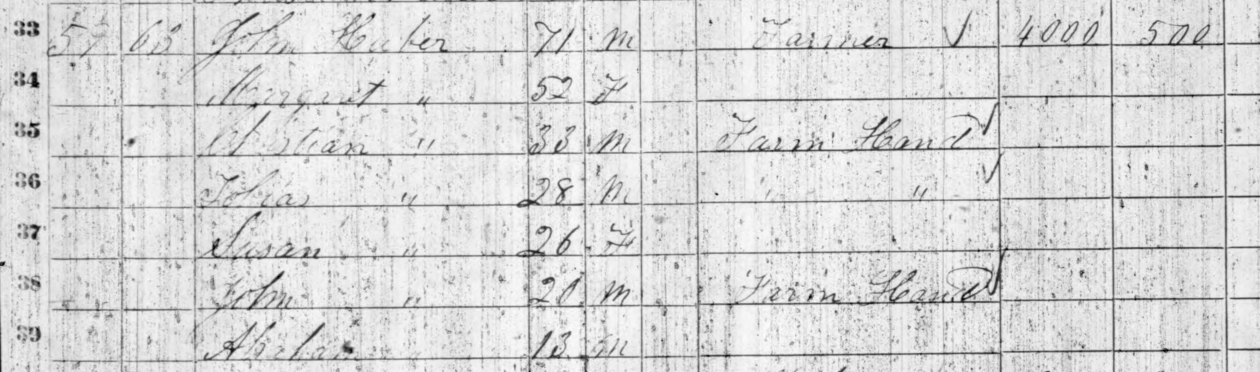

William Adams of Cocalico Township wrote his last will and testament on 21 November 1772. He does not name his daughter, but does name his grandsons, John and William Witman. So, most likely Mary Adams was not only the daughter of William Adams, but also deceased prior to 21 November 1772 when William wrote his will. Futhermore, while our Christopher Weidman did have a son named John, to the best of my knowledge, he did not have a son named William.

There was also connection between the family of Christopher Witman Sr. and William Adams. On 7 April 1749, Christopher Witman and his wife Barbara sold 246 acres of their 356 acres in Cocalico Township to William Adams. This Christopher Witman wrote his last will and testament 18 February 1765 and it was proven on 12 September 1770. In it he names his son Christopher.

Apparently, while our Christopher was married to a woman named Anna Maria, she quite possibly wasn’t Mary Adams, daughter of William Adams. She most likely married Christopher “Witman” in 1748 and was deceased before 1772.

Sarah Buchanan

So, did Christopher marry a member of President Buchanan’s family? A Sarah Buchanan? What do we know about President Buchanan’s family?

I didn’t know anything, but a quick internet search revealed a bio of the president. He was the son of Irish immigrant “James Buchanan, Sr. (1761–1821), a businessman, merchant, and farmer, and Elizabeth Speer, an educated woman (1767–1833).” So, immediately, we know Sarah couldn’t have been the president’s sister, not since her alleged son was born in 1756 and her father was born in 1761 in Ireland. She couldn’t have been an aunt either—though James Buchanan Sr. did have a sister named Sarah who married William Morrison—unless said aunt was significantly older than her brother. Again, the timeframe does not fit.

Conclusion

While I neither confirmed nor disproved that our Christopher Weidman was married to a woman named Sarah Buchanan, I do not believe he could have been married to a “Sarah Buchanan” from President Buchanan’s family. In fact, I found zero evidence that he had a wife named Sarah.

However, I believe I’ve also proven—at least to myself—that the conclusion that he married Anna Maria Adams in 1748 may, quite likely, be incorrect. I now think that marriage was between the Adams and “Witman” families, not our Weidmans. At a minimum, I’ll need to do more research.

Now I’m adding another item to my research agenda.

Who was Anna Maria (___) Weidman?