In a previous post, I wrote about the problem of determining how many Henry Hoovers there were in Martic Township. I listed the land warrants and patents and subsequent deed transfers for several parcels of land. But I didn’t go into any detail on what these documents actually said. So, in this post, I plan to go into more detail on how I used deeds to distinguish between multiple men of the same name who lived in the same area at the same time.

Note: I’ve used Hoover as the primary spelling of the surname through this post. The spellings–Huber, Hoober, Huver, Hoover, and Hover–were all used interchangeably throughout documents from the 18th century. Specific spellings directly from a document are shown here in quotes.

One Henry Hoover

The research that I’ve seen online and in published materials says that there was one Henry Hoover who owned land on Pequea and Beaver creeks at the junction of present-day West Lampeter, Pequea, Providence and Strasburg townships. He married Katherine Good, daughter of Jacob Good, and died in 1757. Richard Warren Davis has apparently identified him as a son of Jacob & Barbara (__) Huber of Conestoga Township.

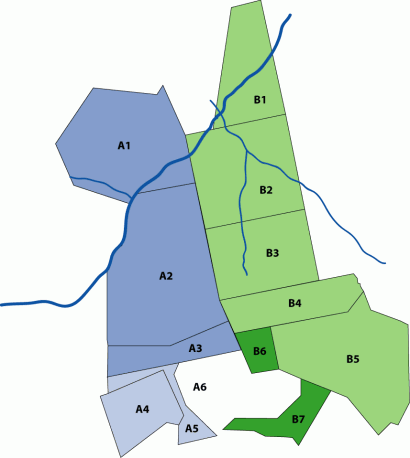

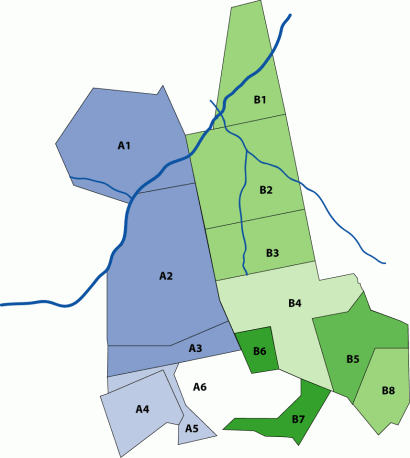

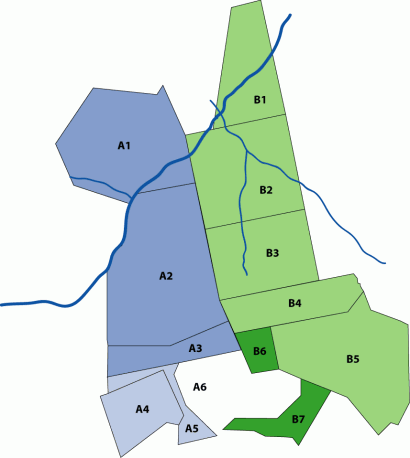

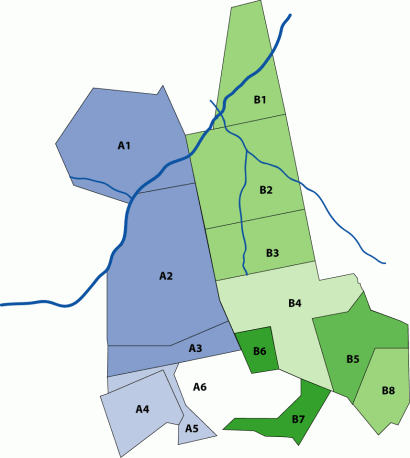

Hoover land patents in Conestoga/Martic Township area

In 1733, Michael Shank sold his rights to 250 acres at the junction of Pequea and Beaver creeks to Jacob Good and Henry Hoover. Jacob took 106 acres to the south and Henry took 144 acres to the north. These tracts are labelled B2 and B3 on the map. Both were warranted in 1717 to Shank and patented 15 April 1740—along with tract B4 which was originally surveyed to Jacob Good—to “Henry Hoober.” Also in the year 1733, Henry Hoover warranted 160 acres in Martic Township (B1). He never surveyed land for this warrant.

Jacob Good bequeathed a tract surveyed to him, containing about 180 acres, and all improvements to his son-in-law “Henry Hover” in his last will and testament, written 12 September 1739. Henry was named sole executor and required to provide for Jacob’s widow Barbara and to allow her to live in the “dwelling house.” Letters testamentary were issued to “Henry Houer” 22 January 1741/2. An inventory was filed for the estate in 1741/2.

Henry Hoover warranted an additional 171 acres in Martic Township on 13 November 1744 and had it surveyed on 20 December 1744 (B5). This plus the land mentioned previously brings the total acreage owned by Henry Hoover in Martic Township to 489 acres.

“Henry Huver” left a will, dated 27 August 1757 and proven on 29 December 1757. In it, he left to “John Huber the Half of my Real & Personal Estate of Lands Money & Goods to him forever & ye other half unto my Daughter Elizabeth Bayers she to have ye same divided between the aforesaid John Huber her Brother; & ye said Elizabeth Bayers Equally & Impartially.” He named his “loving Friends Martin Bear & Henry Huber Executors.” [Emphasis mine.] Letters testamentary were granted to his two executors on 29 December 1757. An inventory was filed on the estate of “Henry Hoover” a weaver of Martic Township in 1758.

John and Elizabeth (Hoover) Boyers sold their 1/2 share of Henry Hoober’s land to her brother John on 8 February 1758. The deed specifies this land in metes and bounds that match tract B2 on the map, containing 144 acres. “John Huber” wrote his last will and testament on 9 January 1793 and it was proven on 3 April 1799. He directed that all his estate–both real and personal–should be sold to the highest bidder. On 14 May 1799, his executors “Henry Huber,” his son, and “John Huber,” a friend, sold 144 acres to Henry Bowman.

So, if the land inherited by John Hoover and Elizabeth (Hoover) Boyers totaled 144 acres, what happened to all the other lands warranted or patented to “Henry Hoober?”

Two Henry Hoovers

We know there were two Henry Hoovers of legal age by 1757–as “Henry Huver” named his friend Henry Huber as one of his executors in the will he wrote in August of 1757. His neighbor “Jacob Huber” (A1 & A2 on map) also named his friend “Henry Hoover” as one of his executors in his will, written 29 July 1759. The question is whether or not there were two men of that name, of legal age, by 1740 when the multiple tracts were patented. The answer, I believe, can be found by examining later deed records.

Martic Township Hoover property

On 6 June 1767, Henry and Katharine Hoover sold several tracts of land to John Hoover and Jacob Hoover. They sold two tracts to their son John Hoover—80 acres from the tract of 106 acres (B3, map #2) patented to Henry Hoover in 1740 and 64 acres (B5, map #2) from the parcel of 171 acres warranted to Henry Hoover in 1744. They sold the residue from these two tracts—137 acres (B4, map #2)—to Jacob Hoover.

But if Henry died in 1757, how did he and his wife sell land in 1767? The deeds to John Hoover were typed, indicating that a copy had been made from the earlier handwritten record, likely sometime in the 20th century. Could the typist have read 1757 as 1767? Certainly, it’s possible.

However, the land the couple sold to Jacob was sold by his executors on 25 August 1790. The deed was recorded 7 October 1819 and appears to be the handwritten record of the recorder. It, too, indicates that Henry and his wife sold the land to Jacob on 6 June 1767. This date was most likely copied from Jacob’s unrecorded deed of his purchase of the land from Henry and Katharine Hoover.

Furthermore, the 171-acre tract warranted to Henry Hoover 13 November 1744 was patented to the warrantee, i.e. Henry, on 14 April 1761. Since “Henry” died in 1757, this land could not have belonged to the same man.

Additionally, the John Hoover who inherited land in Henry Hoover’s 1757 will died in 1799, leaving a will directing that his land be sold. His will named his widow Ann and eight children: “Henry, Mary, Jacob, John, Christian, David, Anne & Christina.”

The John Hoover, who purchased land from Henry and Katharine Hoover in 1767, died intestate prior to 21 April 1810. This John left a widow named Mary and nine children: “Mary the wife of Peter Huber aforesaid, Barbara Huber, John Huber, Christina Huber, Esther Huber, Abraham Huber, Ann Huber, Susanna Huber, and Elizabeth Huber.”

As you can see, there were two men named John Hoover, both sons of men named Henry Hoover who lived in Martic Township on adjoining properties. Could one man have two sons with the same name? Yes, but usually not two living sons.

Furthermore, even though three of the pieces of land under discussion were patented on 15 April 1740 to “Henry Hoober,” only one of them could have been owned by the Henry who died in 1757. Therefore, there must have been two Henry Hoovers–one who split Michael Shank’s land with Jacob Good and died in 1757, and Jacob’s son-in-law, who patented his lands, selling them to his sons in 1767.

Is there any other evidence to support this conclusion? Yes.

Tax records provide some additional information. There were two Henry Hoovers listed in Martic Township tax records for 1751 and 1757. A Henry Hoover also appears in tax records for 1758 and 1759. Also, Jacob Hover, “Henry’s son,” is listed in Martic Township tax records in 1769 and 1770, though Henry is not. And as far as I can tell from the records, the Henry who died in 1757 did not have a son named Jacob.

Conclusions

Based on the deed records, there were two Henry Hoovers–let’s call them A and B. Henry Hoover (A) split Michael Shank’s tract with Jacob Good in 1733. Henry (A) took tract B2. Tract B1 was part of land warranted to Henry (A), but never surveyed or patented. Henry (A) died in 1757, leaving all his estate to his son John and daughter Elizabeth. His wife was not mentioned in the will, indicating that she was already deceased, nor were any other children mentioned.

Henry Hoover (A) and his unknown wife had children:

- John Hoover, born before 1737, probably died in March 1799, but definitely before 3 April 1799. John and his wife Ann had children (listed in the order from John’s will):

- Henry Hoover, born before 9 January 1772

- Mary Hoover

- Jacob Hoover, born 1756-1774

- John Hoover, born before 1780

- Christian Hoover, born before 9 January 1772

- David Hoover, born before 1771, died sometime after 1803 in Upper Canada

- Ann Hoover, born 16 January 1768, died 25 March 1780, married Abraham Gochenour

- Christina Hoover, born before 1778, unmarried as of 1801

- Elizabeth Hoover, born before 1737, died circa 1809 in York County, married John Boyer/Byer/Beyer

In his 1739 will, Jacob Good left his land to his son-in-law, Henry Hoover (B). This Henry took tracts B3 and B4, patenting them in 1740 (before his father-in-law died, possibly at Jacob’s direction) and warranted tract B5 in 1744. Henry was married to Katharine Good. He and his wife sold the majority of his land to his sons John and Jacob in 1767 and Henry does not appear in the records for Martic Township after that.

Henry and Katharine (Good) Hoover had children:

- Jacob Hoover, born before 1736, died between 13 March and 9 June 1788, married Barbara (___). Barbara Hoover likely died in 1810 when an inventory was produced in Martic township. An administration account was filed in 1813 by John and Martin Huber. Jacob and Barbara had children:

- Henry Hoover, born circa 1764

- Jacob Hoover, born circa 1766

- Barbara Hoover, born circa 1768

- Christian Hoover, born circa 1771-1774

- John Hoover, born circa 1771-1774

- Martin Hoover, born circa 1774, possibly married Maria Eshleman in 1799

- John Hoover, born before 1746 and died intestate before 21 April 1810 when his land was partitioned by the Orphans Court. He married Mary (___). She died prior to 4 December 1826. John and Mary had children:

- John Hoover, died between 17 November 1815–25 July 1818, unmarried and without children

- Mary Hoover, born circa 1766-1774, died after 4 December 1827, married Peter Huber, son of John and Barbara (___) Huber of Martic and Conestoga Townships

- Christina Hoover, born circa 1780, died before 3 March 1875, unmarried

- Barbara Hoover, born circa 1780-1790, died before 16 June 1841, unmarried

- Esther Hoover, born circa 1780-1790, died before 15 March 1832, unmarried

- Abraham Hoover, born circa 1785, died 1864, married Mary Huber, daughter of Abraham and Anna (Huber?) Huber

- Ann Hoover, born circa 1775-1794, died before 1 January 1828, unmarried

- Susanna Hoover, born 30 May 1789, died 16 July 1874, unmarried

- Elizabeth Hoover, born circa 1791-1794, died after 27 March 1875, married Henry Krug/Krieg before 4 December 1826

- Daughter (possibly Barbara) Hoover, married Jacob Hoover (possibly the son of Jacob and Anna Huber)

Identifying the specific land parcels and tracing them through multiple types of records for subsequent generations was crucial in determining that there were two men named Henry Hoover living on adjoining properties on Beaver Creek. The name and location alone were simply not enough information.

Have you run into this problem? What records did you find useful in distinguishing between two people of the same name and in the same location?