A Beautiful Circle A DNA Circle Happy Dance

If you’ve been following along with my research through the years, you know that I’ve spent a significant amount of time researching the Hoover family. I’ve been determined to identify the ancestry of my 3x great grandfather Christian Hoover.

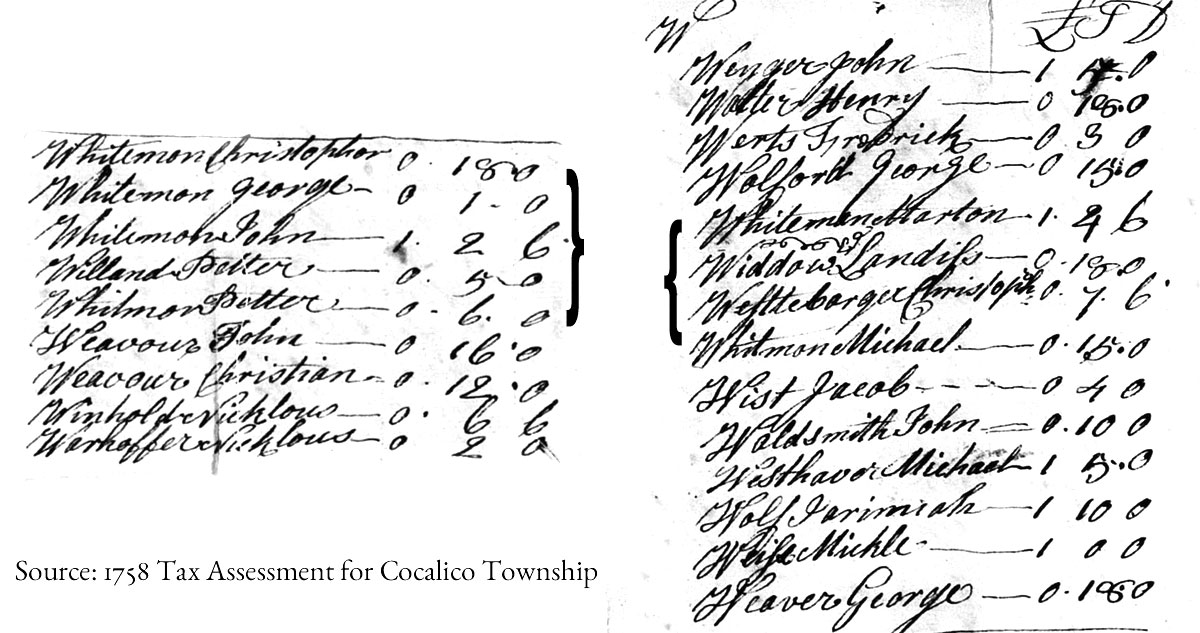

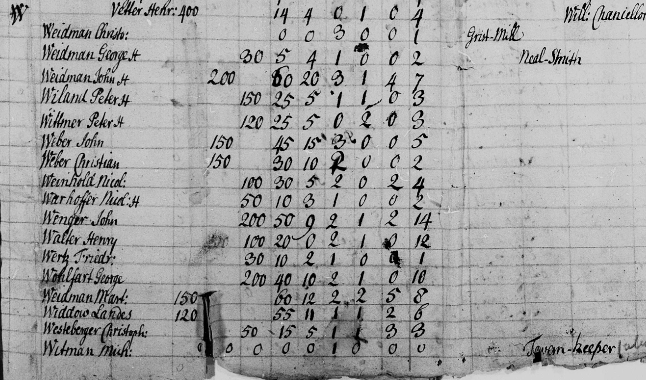

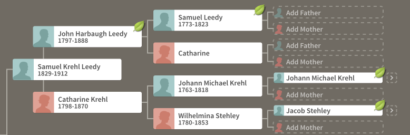

I had located information that led me to believe he was the son of Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover of Armstrong County and could trace the family back to an immigrant ancestor named Andreas Huber. Later I discovered that the connection I’d made between Philip’s grandfather George Huber and Andreas was incorrect. George was actually the son of the immigrant Michael Huber. But, while I could build a circumstantial case that Philip and Hannah were Christian’s parents, I didn’t have any direct evidence of the connection.

And then I took a DNA test.

DNA Circles

This spring I took a DNA test. I was mostly curious about what the results would be. I figured any proof I might get from DNA would come from Y-DNA tests on various male family members.

I found a lot of matches through Ancestry. Like 130 pages of DNA matches. It was totally overwhelming. Some of those matches shared their family tree, some didn’t. Some share ancestors, some share ancestral surnames, some I had no clue where we matched, and some I knew—even without a family tree—exactly who they were and how we were related. But while it’s all very interesting, I mostly haven’t learned anything new.

Then I made my family tree public so I could get DNA circles.

What are DNA circles?

According to Ancestry, they are “a great way to discover other members who are related to you through a common ancestor.” The Legal Genealogist has a great, simple explanation of DNA Circles. She does a great job of explaining what they mean—and what they don’t mean.

In order for a DNA circle to be created for you, several things need to happen. First, you have to have a public family tree. This applies to your DNA matches, too. If you have DNA matches through a common ancestor, but they either don’t have family trees at Ancestry or haven’t made their tree public… no DNA circle.

Two, you have to share a common ancestor in your public family trees and that common ancestor must be within six generations of you—a 4x great grandparent or closer. So, if you’re hoping to see a DNA circle for descendants of your 5x great grandfather, it’s not gonna happen. Furthermore, that common ancestor must be easily identifiable as being the same person. Significant differences in name, dates, etc. may nullify the connection—meaning no circle.

Three, you have to have a DNA match to at least two other people who also share the common ancestor within those same six generations in their public family tree. Oh, your relations—siblings and first cousins—all get lumped into a family group and count as a single person. So, those two other DNA matches must be at least second cousins.

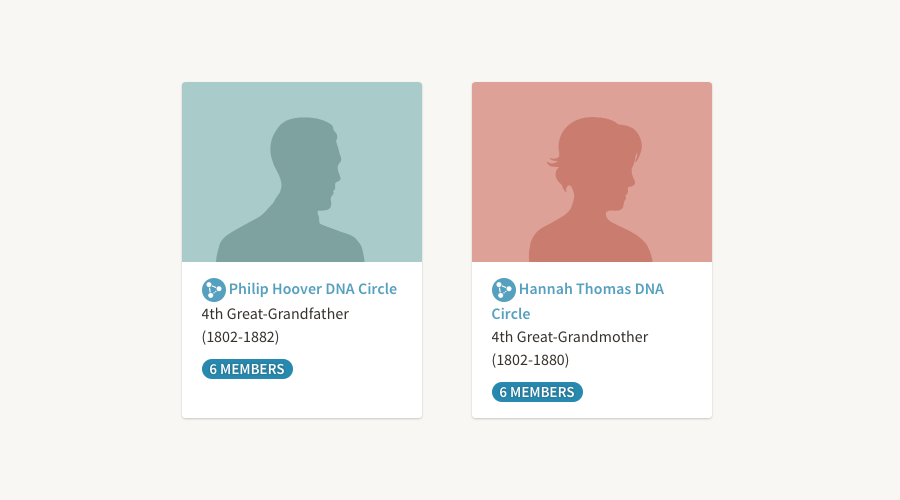

So, after all those must haves in order to create a DNA circle, I actually have circles for Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas among my matches! I can not tell you how happy that made me—you’ll just have to imagine the happy dance I did when they came up in my account.

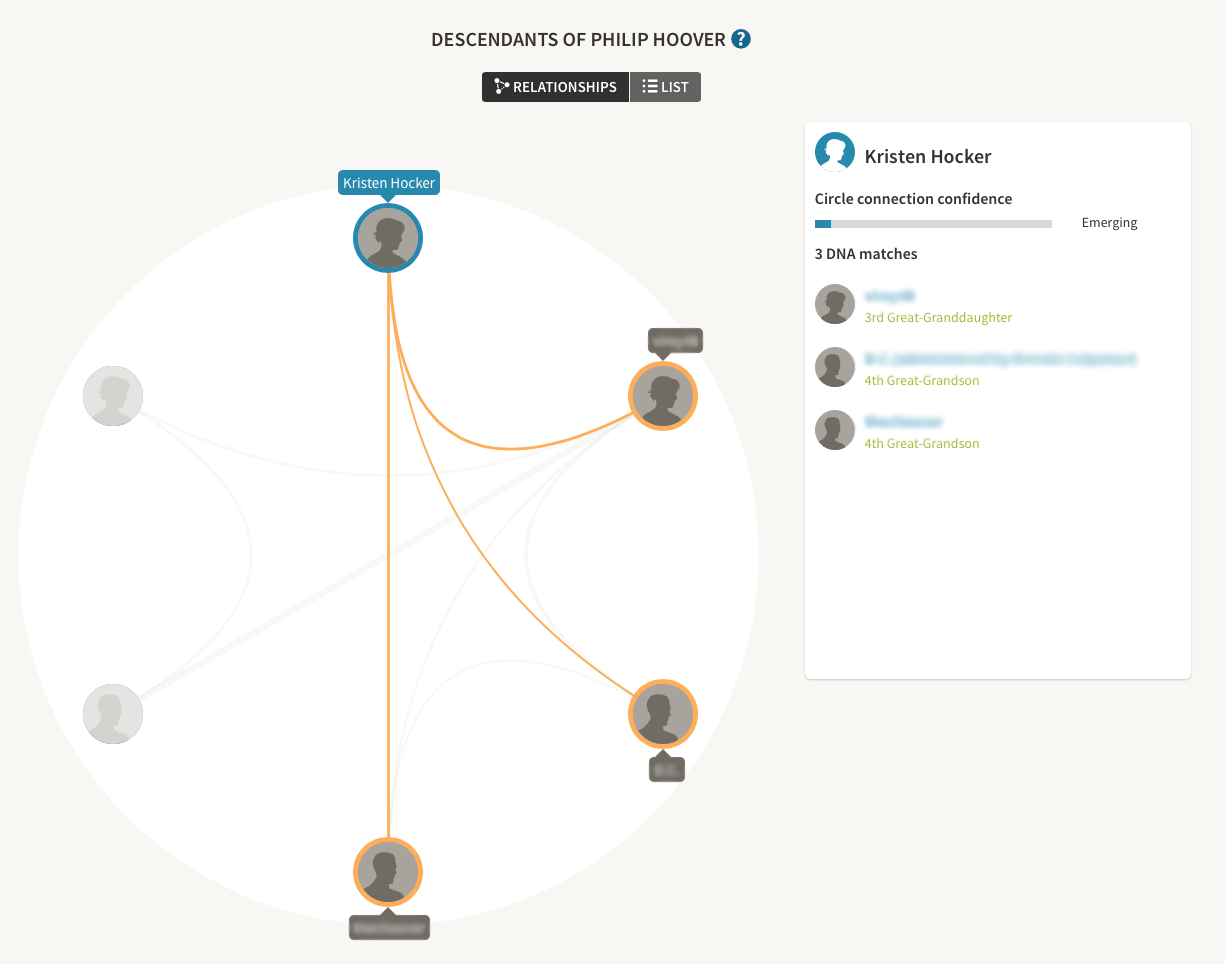

Take a look at this diagram and I’ll explain how these matches work.

I have three DNA matches in this circle. AncestryDNA does not tell us whether or not we all share the same DNA segments. But each of us shares DNA with the other three matches.

Three of us are descendants of my 2x great grandfather Samuel Thomas Hoover and his wife Victoria Walker. Our great grandfathers were brothers. We are third cousins. The fourth person is a descendant of one of Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover’s daughters. She is one generation closer to the couple, than the other three, so she is a 3x great granddaughter, while we are 4x great grandchildren.

The other two people in the circle do not share DNA with me or the other two descendants of Samuel and Victoria (Walker) Hoover. They only share DNA with the female descendant of Philip and Hannah.

Based on my research, Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover had the following children:

- Christian Hoover (c1821-1 Oct 1887)

- Mary Ann Hoover (22 Nov 1825-?)

- John Thomas Hoover (4 Nov 1827-?)

- Margaret Hoover (c1831-?)

- Barbara Hoover (c1833-?)

- William Hoover (c1835-?)

- Jacob Hoover (8 Feb 1836-14 Sep 1909)

- Ralston Hoover (c1839-13 Jun 1862)

- Sarah Hoover (1 Jul 1842-8 Aug 1906)

- Samuel M. Hoover (c1845-?)

According to our family trees, the six persons in this DNA circle are descended through three of Philip and Hannah’s children: Christian (aka Christopher), Margaret, and Sarah. Christian’s descendants share matching DNA with Sarah’s descendant, but not Margaret’s descendants. Sarah and Margaret’s descendants also share DNA.

So does this prove that our Christian was the son of Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover? Well…

I believe it does prove a biological connection between Christian and this family. It’s possible that he could be their eldest son. It’s also possible that Philip is his uncle or his cousin. The research I’ve done into this family provides enough circumstantial evidence to say the Christian is likely the son of Philip and Hannah, not a nephew. But I still have unknowns in prior generations, including two of Philip’s uncles. Without knowing exactly how our DNA matches, I can’t say anything for sure.

But, you know, I’ll take it. It’s one more data point that backs up my supposition that my 3x great grandfather was the son of Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover. And I’ll keep looking for more. Until I find evidence proving otherwise, I’m going with it.

And for some ancestors, this is what has happened. Ancestry’s shaking leafs have shown me records that I don’t have. And helped me learn more about them. For the most part, however, it’s shown me records that I already have or would have easily located by doing a basic search for that ancestor.

And for some ancestors, this is what has happened. Ancestry’s shaking leafs have shown me records that I don’t have. And helped me learn more about them. For the most part, however, it’s shown me records that I already have or would have easily located by doing a basic search for that ancestor.