Lillian (Snyder) Greulich and son

This photo was most likely taken at the Witmer farm about 1911. The clothing she’s wearing match her outfit in a group shot taken with her parents, grandparents, and other family members.

This photo was most likely taken at the Witmer farm about 1911. The clothing she’s wearing match her outfit in a group shot taken with her parents, grandparents, and other family members.

I’ve been spending a lot of time—a real lot of time—working with my Ancestry DNA, FTDNA, and GEDmatch results, working through my match lists, compiling data, and, where I can, identifying my most recent common ancestors with various matches. It’s a great deal of work. And most of the time I feel like I’m flailing about, trying to swim in water that’s really too deep for my abilities.

As I was traversing a match’s GEDCOM file searching for a common surname—unsuccessfully, I might add—it occurred to me to wonder why I was doing so. Just what did I hope to gain from all this work?

It’s common online to see folks trying to identify relatives in order to identify their or a relative’s birth family. That’s not my situation. I know who my parents, grandparents, and great grandparents are—and my DNA matches confirm this.

So, why am I spending so much time analyzing my results? What do I get out of it? I took the test for fun. I thought it would be interesting to see my ethnicity results, maybe find some cousins. I’ve already done so much research to build the “paper trail,” I didn’t really consider that it might be useful otherwise.

But recently I’ve been spending significantly more time working with the DNA results, than I have been researching. Maybe it’s time to stop and consider whether that’s a productive use of my time.

Here’s that I’ve been able to come up with so far.

Not particularly exciting and rather obvious, but a true and useful goal. My DNA matches have become another piece of source data to add to a proof argument. The fact that I share DNA with other descendants of Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas of Armstrong County strengthens my assertion that my ancestor Christian Hoover was their eldest son. As more matches come in which share DNA with their descendants—or those of their ancestors—the stronger my argument will grow.

Since I know the majority of my ancestry back six generations, and a number of lines back even further, sounds like a simple thing to do, right? Uh huh. Wouldn’t that be nice? There are actually several factors that complicate this process.

First, in order to find how you and a DNA match are related, you need to compare ancestors. Sometimes it’s as easy as finding a shaking leaf on Ancestry. It’s more common, however, to find no family tree to examine, a private family tree, or a tree with only couple of generations—all marked “private”—with no names or dates. Somewhat less than useful. Furthermore, when you contact matches hoping to collaborate, you get no response.

Second, my ancestors on both sides of my family tree arrived in Pennsylvania, decided it was a good place to live, and then never left. Although this really helps with the document research, it complicates the DNA research. You see, they not only stayed, but they married. Then their descendants intermarried. So, finding how I match that 4th-6th cousin prospect is not always as simple as locating the common surname in a family tree. Occasionally, there are multiple common ancestors. Which one (or more) is the reason for the match?

Which brings us to the next difficulty—Ancestry’s total lack of useful tools to analyze the actual DNA. At most, you can identify the overall amount to DNA you share and the number of segments. Because there is no means of identifying segment or chromosome information; there is no method to triangulate your matches. You can’t determine whether the DNA you share with several matches is actually the same segment on the same chromosome—or that they share that same DNA between them, too.

To actually use Ancestry DNA results for more than just guessing, you need to upload it to GEDmatch or Family Tree DNA so that you can access segment and chromosome data. You can upload to both for free—although to use FTDNA’s tools, you’ll need to pay a small fee. It was $19 when I did it and well worth the price.

Several of my Ancestry matches have already uploaded to both places. Because they’ve done so, I was able to identify the specific segments we share from our common ancestors. It’s cool to see that I likely got about 30 centimorgans (cM) of DNA on chromosome 16 from my 4x great grandfather George Walker of Boggs Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania. A shorter segment on chromosome 16 may have come from his in-laws, Andrew and Catharine Margaret (Fetter Fetzer) Walker.1

This one is the trickiest of my three goals. Christian Hoover was a brick wall ancestor for some time. Research, however, pointed to a possible location and family. DNA, so far, has been supporting that conclusion. More on that in another post.

Another brick wall ancestor is Jefferson Force. I believe he was orphaned at a young age, possibly as early as age ten. My research to date has not yielded much. I would like very much to identify his parents. Identifiable DNA matches between other Force descendants to some of Jefferson’s descendants might provide other avenues to explore. Jefferson’s parents would be my 4x great grandparents. This is pushing the limits of usable DNA information as 25% to 50% of 4th cousins share no DNA. Someone of my generation would likely be my 5th cousin, making it even a bit more unlikely a share DNA with any given 5th cousin.

So now that I’ve identified some goals for using DNA testing in my genealogy, it’s time to come up with a plan and action items. What exactly do I need to do to accomplish them? More testing will likely be required. Any aunts, uncles, or cousins out there who want to volunteer to take a DNA test?

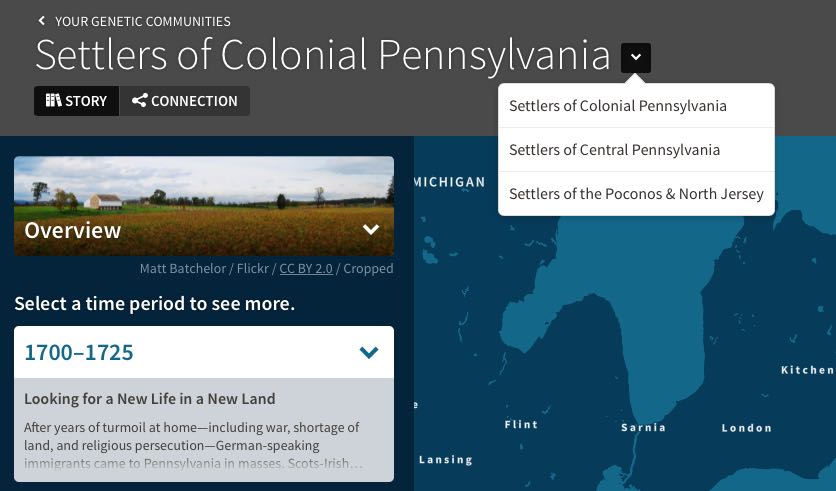

Several weeks ago, Ancestry released their newest tool: Genetic Communities. These communities are based on some pretty cool work with the DNA of millions of AncestryDNA test-takers. This work was published in Nature Communications. You can read Ancestry’s paper “Clustering of 770,000 genomes reveals post-colonial population structure of North America” for more information. (It’s neat stuff!)

After the tool was revealed, there were a lot of great articles explaining it, how it works and how to use it, including:

(These blogs are good sources for other information on genetic genealogy and DNA testing, too!)

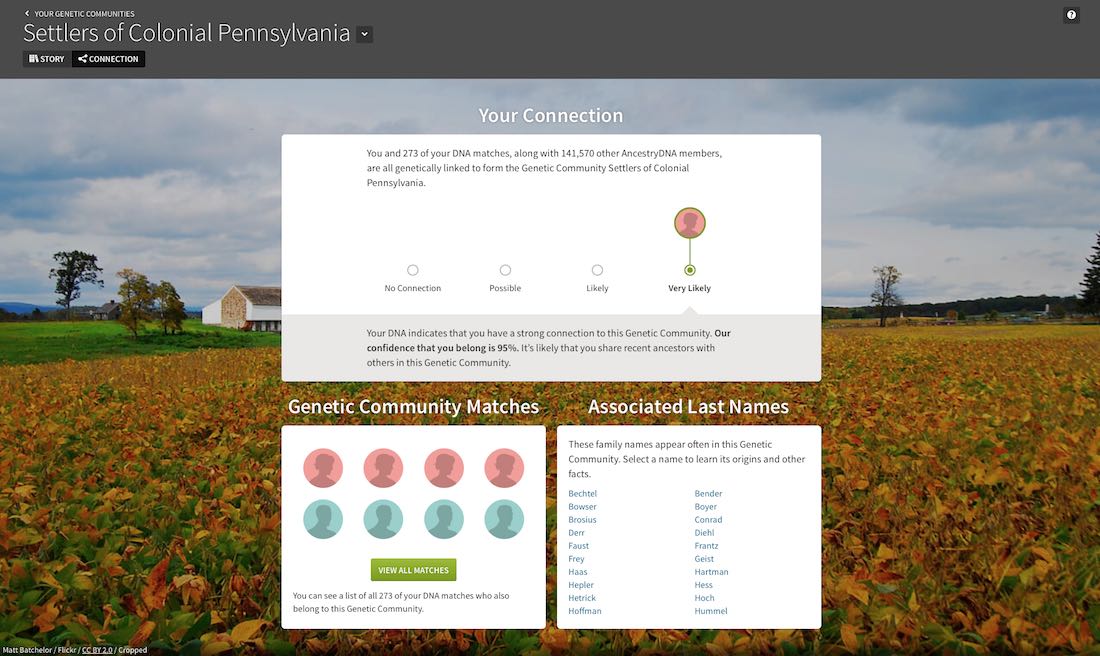

My genetic communities were exactly what I would have expected from my research. I’m part of the Settlers of Colonial Pennsylvania and its two subgroups, Settlers of Central Pennsylvania and Settlers of the Poconos & New Jersey. The subgroups even match up to my paternal and maternal lines.

Although I was hoping to see some European communities,1 I’m not disappointed in my results. There were no surprises that could launch new and exciting areas to research, but that’s okay. There is great value in consistency in genealogical research. My DNA results have—so far—been supporting my research-based conclusions.

Ancestry’s confidence that I genetically belong in this community is 95%. This is a very good thing. It means that my work is most likely valid and correct. There may be tweaks that need to be made the farther back I go, connections to re-evaluate, but overall the foundation is sound. I am following the right paths.

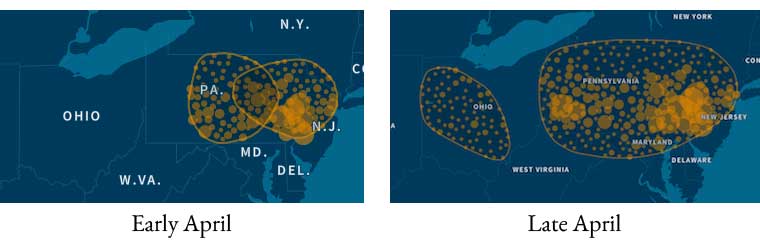

One thing I’ve noticed is that the communities are not static. The Settlers of Colonial Pennsylvania included only Pennsylvania in the original release, but now includes all of Pennsylvania and portions of Ohio.

This demonstrates, I believe, later migration paths of descendants of those early Pennsylvania settlers as they left eastern and central Pennsylvania. The article in Nature Communications includes a graphic that visually shows some of this migration by showing where the “Pennsylvania community” lived 3-9 generations ago.

So, it’s possible that as more people test—especially non North Americans—these communities will be refined even further and I just may get to see that Scottish community I was hoping for.

I recently came across a reference to a Christopher Hocker who was living in Ohio in the early 1800s. As you recall, Johann George Hacker’s son Christopher was allegedly “of a rather headstrong disposition; he left his wife here in Montgomery county and went to Ohio, lived and married there a second time.”1

Christopher was born about 1772 in Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, son of Johann George and Anna Margaretha (Weidman) Hacker.2 He married Catharine Daub, daughter of Henry and Christianna (Wohlfarth) Daub, 10 April 1792 at Saint Michael’s Lutheran Church in Germantown.3

The couple lived in Whitemarsh Township until about 1800. In 1805, he purchased a tavern and acreage from his father-in-law in Sandy Run.4 According to deed records, Christopher (Innkeeper) purchased a lot in Whitemarsh Township from the daughters of Jacob Edge on 1 April 1807.5

About 1808, Christopher apparently ran into financial troubles. On 5 April 1808, Christopher (Farmer) and Catharine Hocker sold this land to Daniel Hitner.6 He also gave up the tavern to assignees John Wentz, George Price, and Samuel Maulsby.7 According to family legend, Christopher found himself in debt and fled to Ohio.

I haven’t been able to track Christopher down in Ohio. His son George, who later returned to Whitemarsh Township, was said to have been born there in 1814. And we know Christopher was still alive as of 1821 as he was named as one of the surviving children in his father’s estate files.8

So, just where did Christopher go?

Maybe he was living on Licking Creek in Falls Township, Muskingum County, Ohio. I found reference to a Christopher Hocker living there in a Cumberland County Historical Society journal article about Jacob Fought, a Carlisle tavern keeper. About Christopher, it says:

“In April 1814, Christopher Hocker, who lived on Licking Creek in Falls Township, Muskingum Counry, Ohio…hired a young man, Asher Nichols, to help take the horses to Philadelphia… Their eastward trip passed through Carlisle, Pennsylvania where they arrived on the sixth or seventh of February 1815. In Carlisle, they stayed at Jacob Fought’s inn, Sign of the Plough and Harrow, located only two blocks from the town center where the courthouse, market, and two established churches were.

On 9 February 1815, Nichols left the inn and stable along with Hocker’s two horses, and without Hocker’s permission. He arrived at Hummelstown, probably the town by that name near Harrisburg. Nichols was found and brought back to Carlisle to stand trial for horse stealing. A great effort was made to seek evidence for this serious accusation. This included sending prosecution and defense interrogatories to the Muskingum County court, which deposed four key Ohio witnesses.

Asher Nichols was indicted on a charge of larceny, for horse stealing, on oath of Christopher Hocker, in the summer of 1815… Asher Nichols was found guilty and sentenced to hard labor. The bills or taxes for witnesses and the docket session findings do not state the term of the sentence.”9

This is the first reference I’ve found to a Christopher Hocker in a specific location in Ohio at a time when Johann George’s son was alleged to have been there. 1814, the year Christopher’s son George was said to have been born in Ohio. This passage also provides several sources to follow-up with—Cumberland County court records and Muskingum County court records—regarding the theft of Christopher’s horses in Carlisle.

Time to get crackin’.

George Houdeshell Family, circa mid 1920s

George W. Houdeshell married Lovina Caroline Force on 20 June 1890. Between then and 1914, they had 12 children, ten of whom survived to adulthood. This Wordless Wednesday features their family photo.

George and Lovina are sitting. One the left are sons Millard Franklin and William Arthur with daughter Martha Rebecca in front of them. The youngest daughter is on the right, Georgia Caroline. I do not know the exact identities of the four women in the back row—do you?—but most likely includes four of the following daughters: Thelma Mae, Carrie Edna, Anna Belle (if taken before 3 September 1924), Ida Rachel, Wilhelmina L., and/or Nora Melinda.

William Bonnington, my four times great grandfather, was born about 1816 most likely in Bowden, Roxburghshire, Scotland.1 He was the son of Robert and Agnes (Inglis) Bonnington.2 He died 11 June 1885 in his brother’s house in Bowden.3

About 1838, he married Margaret Purves4 (or Fairborn).5 She was born about 1821 and died between 1844 and 1847. William married for the second time on 9 July 1847 in Melrose, Scotland to Mary Reavely.6 She was born about 1825 in Galashiels, Selkirkshire, daughter of Mark and Margareth (Paterson) Reavely, and died 21 April 1855 in Newington and Grange, Edinburgh.7 After her death, William married for the third time to Elizabeth Thomson on 16 June 1857 in St. Boswell’s Parish, Roxburghshire.8 Elizabeth was born about 1803, daughter of James and Janet (Goodfellow) Thomson, and died 15 November 1880 in the district of Bathgate.9

William worked as a joiner, a carpenter, and apparently moved with his work. In 1841, he can be found in the census for Galashiels, Selkirkshire.10 By 1851, he and family were in Ladhope, Melrose, Roxburghshire.11 Ten years later, the family was in Colinton, Edinburgh, Midlothian.12 He and third wife Elizabeth, as well as his daughter Isabella, were in Ilkley, Yorkshire, England in 1871.13 By 1881, William was living alone with a domestic in Bathgate, Linlithgow.14

William and Margaret (Purves) Bonnington had children:

William and Mary (Reavely) Bonnington had children:

This post is part of a blogging challenge entitled 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks, created by Amy Crow of No Story Too Small in 2014. Participants were to write about one ancestor every week. I’m revisiting this challenge for 2017. This is my thirteenth 52 Ancestors post, and a make-up post for week twelve.

James Smith, my three times great grandfather, was born about 1812 in Whitburn, Linlithgow, Scotland1 to Thomas and Agnes (Nimmo) Smith and died on 8 February 1856 at age 44 in Whitburn.2 He was an “engineer,” a.k.a. engine worker, who worked in the coal mines.

On 25 December 1840, he married Isabella Aitken, daughter of William Aitken and Marion Brown of Lanark, Scotland.3 Isabella was born 27 February 1816 in Carnwath4 and died 1 December 1856 in Whitburn.5 Both she and James were buried in the Whitburn church yard.

On Sunday, 6 June 1841, the couple was living with Isabella’s parents at Auchengray in Carnwath parish.6 William and his son John were wrights, son-in-law George Tweedie a laborer, and son-in-law William Smith an ironstone miner.

By 30 March 1851, James and Isabella and their children were living at Crossroads in the parish of Whitburn in Linlithgow.7 They had apparently moved there by 1844 as all their childrens’ birthplaces are listed as Whitburn.

1856 was a terrible year for Thomas, Marion and William Smith, James and Isabella’s three children. After the death of their parents in February and December, they likely went to live with James’ brother and sister: William and Margaret. Marion died 11 May 18578 of hydrocephalus, likely acquired hydrocephalus caused by an injury, infection or tumor. Thomas and William can be found in Uncle William’s household in Whitburn in 1861.9

Thomas remained in Fauldhouse until his death in 1909. William became a ship’s engineer and travelled abroad, eventually marrying in Edinburgh and emigrating to the United States. He filed an intention to become a naturalized American citizen on 20 September 1886 in Berks County and became a citizen on 12 January 1893 at Harrisburg.10

James and Isabella (Aitken) Smith had children:

This post is part of a blogging challenge entitled 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks, created by Amy Crow of No Story Too Small in 2014. Participants were to write about one ancestor every week. I’m revisiting this challenge for 2017. This is my twelfth 52 Ancestors post, and a make-up post for week eleven.

My 3x great grandfather Jefferson Force’s ancestry remains a mystery. He was born 9 December 1833 in Centre County, Pennsylvania and died 20 October 1910 in Pine Glen.1 He married Susan L. Mulhollan, daughter of John and Emily (Boileau) Mulhollan, on 22 March 1857.2 His obituary reads:

“Died at his home in Pine Glen on Thursday, October 20th, Jefferson Force, a well known and respected citizen of that place, aged 76 years, 10 months and 11 days. During the Civil War, he was drafted in 1864 and received an honorable discharge in 1865. He was married to Susan Mulholland in 1857, with whom he spent a long and happy life. Mr Force was a charter member of Messiah Church, of that place and always remained steadfast to the church of his choice and served its teachings. He leaves a large circle of friends to mourn his loss. Funeral services were conducted by Rev. E.A. Meredith.”3

He enlisted in the Civil War on 20 December 1864 and mustered out 17 July 1865 at Alexandria, Virginia. He served in Company E of the 45th Pennsylvania Infantry Volunteers, 1st Brigade, 1st Division.4 During this period the regiment was involved in the advance on Richmond, Virginia, the Battle of Cold Harbor, the siege of Petersburg, the Battle of Chaffin’s farm, and the Appomattox campaign.5 Jefferson apparently was not wounded during the war, or at least not enough to impact his health.6

After the war, Jefferson lived and worked in Pine Glen, Centre County, Pennsylvania, as a house plasterer and farmer.7 Between 1857 and 1884, Jefferson and Susan had 14 children, five of whom died before 1900—nine daughters and five sons.

It’s been suggested to me that Jefferson was the son of Isaac and Polly (___) Force, who both died in the 1840s based on a Bible owned by Mrs. Agnes E. Shope. I have yet to find evidence to prove this supposition. A number of young Force children—including Martin and Agnes—can be found in a variety of non-Force-led households in the 1850 census enumeration for Centre County, indicating that they were most likely orphaned.

Agnes was born 8 April 1839 and may have been Jefferson’s sister. She named two of her sons Jefferson T. Shope and Martin V. Shope—both names of Centre County Force men. Jefferson also named a daughter Agnes E., perhaps after Mrs. Shope. She lived in Milesburg, Centre County and died in 1922. Martin V. Force (12 Dec 1835-28 May 1902) lived in Pine Glen and was Jefferson’s neighbor.

Jefferson and Susan (Mulhollan) Force had the following children:

Jefferson and Susan are my 3x great grandparents.

This post is part of a blogging challenge entitled 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks, created by Amy Crow of No Story Too Small in 2014. Participants were to write about one ancestor every week. I’m revisiting this challenge for 2017. This is my eleventh 52 Ancestors post, and a make-up post for week ten.

Perhaps not so surprisingly, I’ve fallen behind on my 52 ancestors posts. I’m hoping to catch up. Here’s a short one to start me off.

Henry Jones was born 15 July 1776 in Hilltown Township and died 10 December 1854 in Milford Township, both in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.1 He was buried in Christ Church cemetery in Trumbauersville. He was the son of Edward and Rachel (Lewis) Jones.2

Henry married Martha Bartleson by 1806.3 They lived in Milford Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania where Henry was a farmer and carpenter. Martha died prior to 1 June 1830.

Henry and Martha (Bartleson) Jones had children:

Henry and Martha are my 5 times great grandparents.

This post is part of a blogging challenge entitled 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks, created by Amy Crow of No Story Too Small in 2014. Participants were to write about one ancestor every week. I’m revisiting this challenge for 2017. This is my tenth 52 Ancestors post, and a make-up post for week nine.

I’ve written extensively about my ancestor Christian Hoover and the search for his family. Now that I’ve got another piece of evidence that his parents were Philip Hoover and Hannah Thomas, I thought I’d write about them.

Philip Hoover was born about 1802, most likely on his father’s property on Plum Creek in Armstrong County.1 He was the third son and fourth child of Christian and Barbara (Harmon) Hoover. He died in May 1882 in Burlingame Township, Osage County, Kansas.2

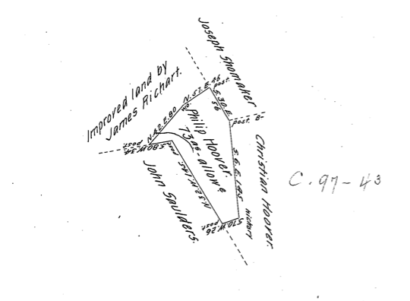

1820 Survey for Plum Creek Township land

About 1820, Philip married Hannah Thomas, daughter of John and Margaretta (Mackin) Thomas. She was born 14 July 1802 in Armstrong County and died 16 August 1880 in Burlingame Township.3 Hannah’s sister Sarah had married Samuel Hoover, Philip’s eldest brother, several years earlier. They lived in Plum Creek Township where Philip was a farmer.

On 21 August 1820, Philip had 73 acres surveyed.4 The survey was returned 28 June 1825. Philip sold this land on 3 February 1826.5 When his father died in 1850, Philip received land from his estate. He sold this land in a series of transactions in January 1876 and April 1877 before he and his wife headed west with his son Jacob and his family. Philip and Hannah both died in Burlingame several years later. Jacob and his family continued moving west, finally settling in Grays Harbor County in Washington by 1889.6

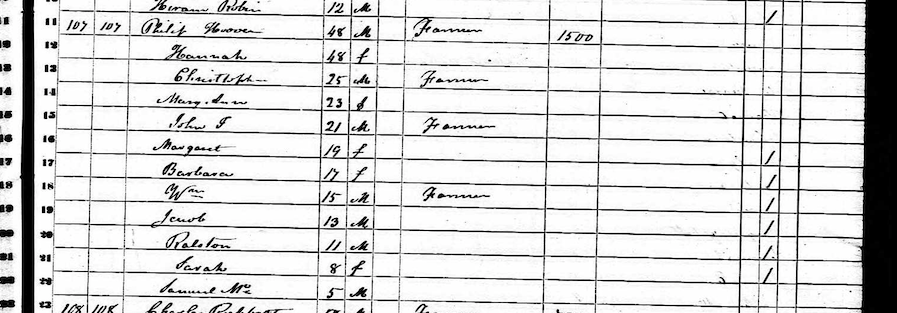

Philip Hoover 1850 census household

Based on census records, Philip and Hannah (Thomas) Hoover had children, born in Armstrong County:

This post is part of a blogging challenge entitled 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks, created by Amy Crow of No Story Too Small in 2014. Participants were to write about one ancestor every week. I’m revisiting this challenge for 2017. This is my ninth 52 Ancestors post, part of week eight.