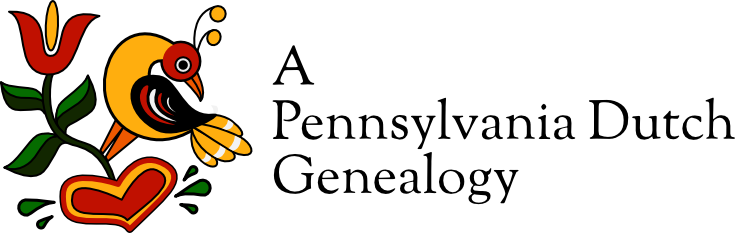

A funny thing happened as I researched the pedigrees of the AncestryDNA matches I shared with my presumed Snyder cousins. A specific surname kept showing up. And it wasn’t Snyder.

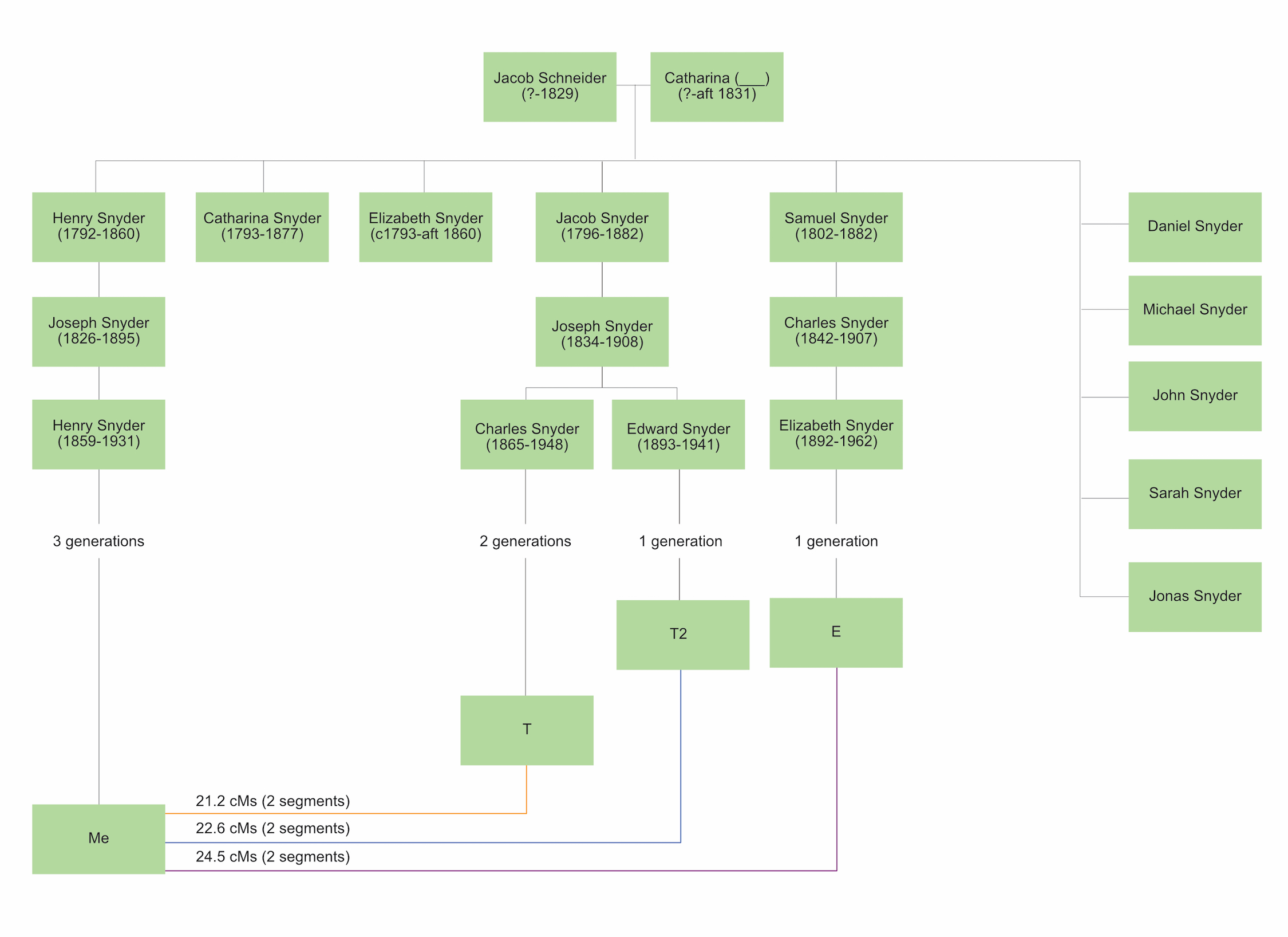

I’ve been trying to prove that my four times great grandfather, Henry, was the son of Jacob Schneider and his wife Catharine of Upper Hanover Township, Montgomery County. Part of that effort has involved working with my AncestryDNA matches to find potential Snyder matches and determine how we match. I believe I’ve identified three Snyder cousins—one possible descendant of Henry’s brother Samuel, and two descendants of a potential sibling Jacob Snyder.

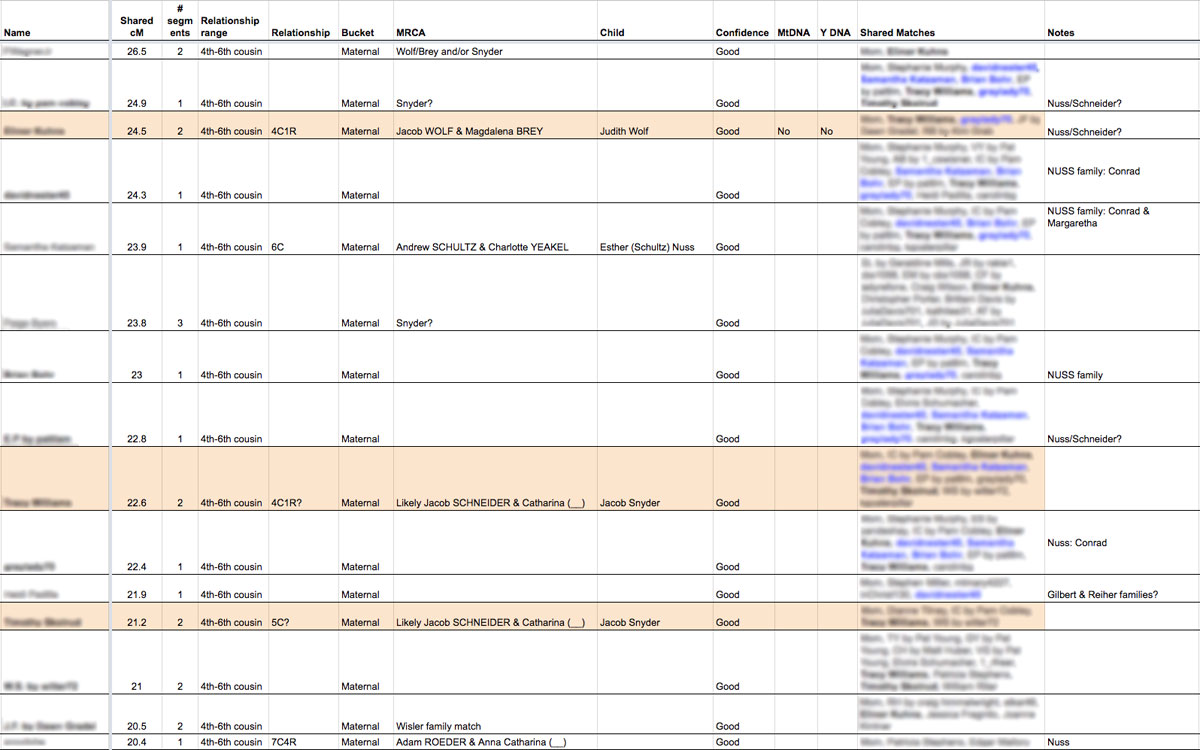

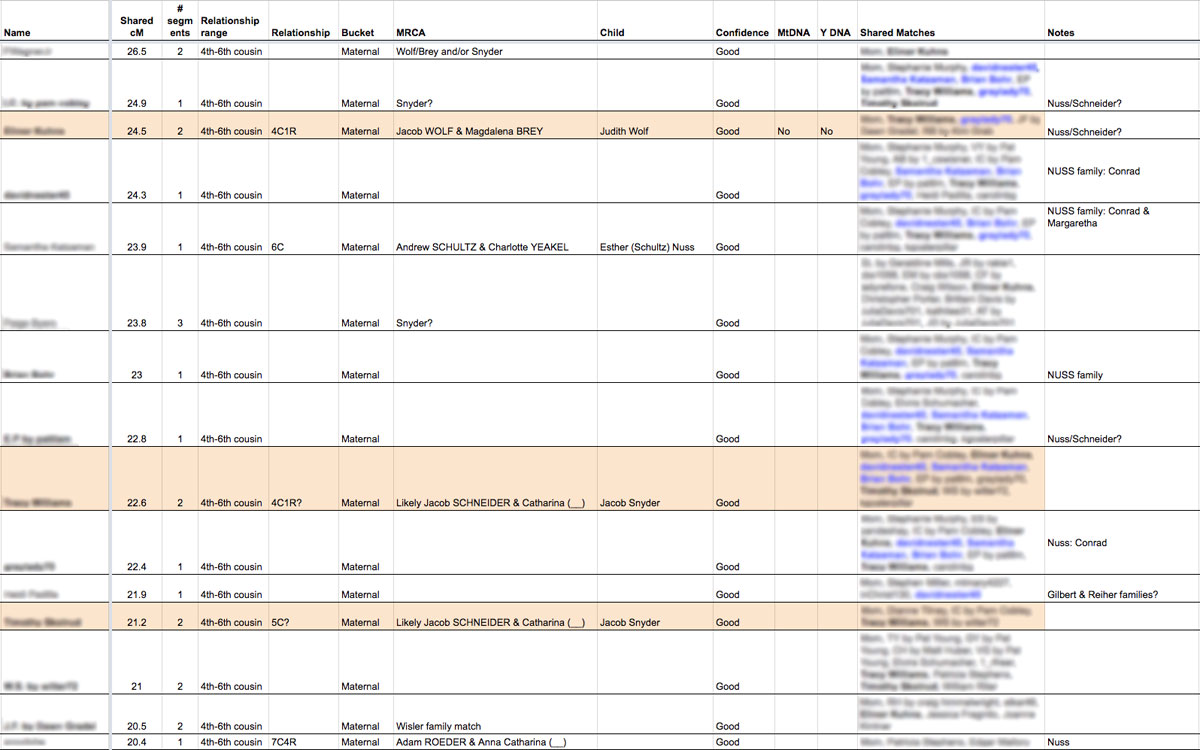

To help organize my research, I entered these three individuals (in orange, below) into their own version of the spreadsheet I’ve been using to track my DNA cousins. One column includes a list of our Shared Matches from AncestryDNA.

I used this to identify individuals who turned up over and over again and entered them into the spreadsheet with their Shared Match list. This gave me a list of top candidates for additional research.

DNA match spreadsheet

Some of them had family trees; most did not. Still, I was able to start building family trees on Ancestry for some of these individuals using searches on Google, Ancestry, FamilySearch, and—where possible—Facebook. A lot of it was “pinging” names to see what I could find online, especially possible associates or family members. If I was able to get to parents or grandparents, I was sometimes able to locate obituaries which helped fill in the tree to the point which I could use census and other records on Ancestry and FamilySearch.

All told I was able to locate ancestors who resided in the Upper Hanover Township/East Greenville area and/or were members of the New Goshenhoppen Reformed Church for four of the Shared Matches (marked blue in the Shared Matches column). They all could be traced back to one of two families. A fifth included one of the surnames, but I haven’t been able to tie it to the same couple, yet.

Who were these people? Conrad Nuss and his wife Maria Margaretha Roeder.

The Nuss/Roeder Family

Conrad Nuss, son of Jacob and Anna Maria (Reiher) Nuss, was born 17 March 1743, Upper Salford Township, Montgomery County, and died 18 March 1808 in Upper Hanover Township. He married Maria Margaretha Roeder, daughter of Johann Michael and Maria Susanna (Zimmerman) Roeder, at New Goshenhoppen on 22 August 1769. She was born 27 June 1745.

They had the following children (italics indicates descendant matches):

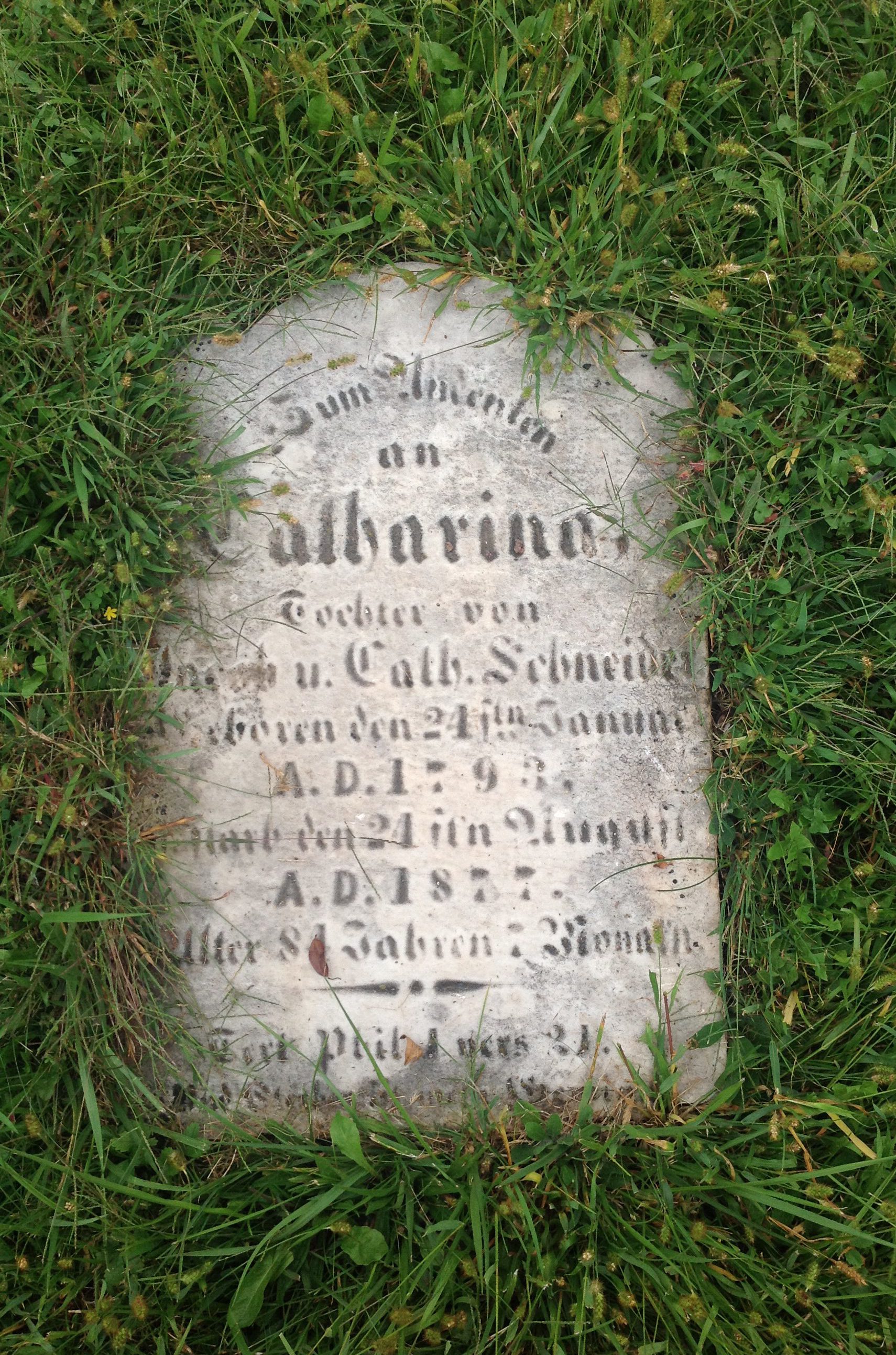

- Catharina Nuss, born 3 May 1770

- Jacob Nuss, born 22 September 1771 and died 1857

- Susanna Nuss, born 3 November 1773 and died before 14 Feb 1775

- Anna Maria Nuss, born 4 May 1775 and died 29 August 1867

- Johannes Nuss, born 4 September 1780 and died 13 March 1852

- Elisabeth Nuss, born 25 December 1752 and died 30 April 1843

- Susanna Catharine Nuss, born 5 May 1785

- Michael Nuss, born 16 June 1787 and died 2 October 1858

- Anna Margaretha Nuss, born 12 July 1789

- Daniel Roeder Nuss, born 19 June 1791 and died 21 December 1867

- Sarah Nuss, born 7 March 1795 and died 25 July 1844

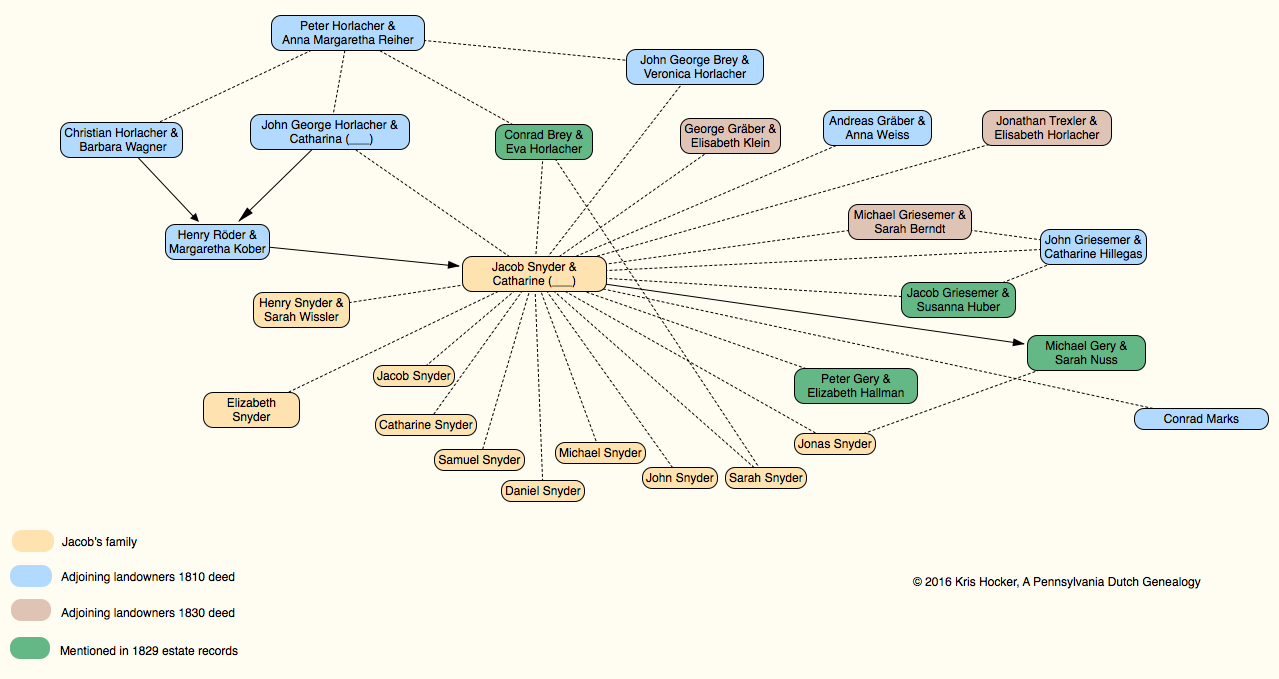

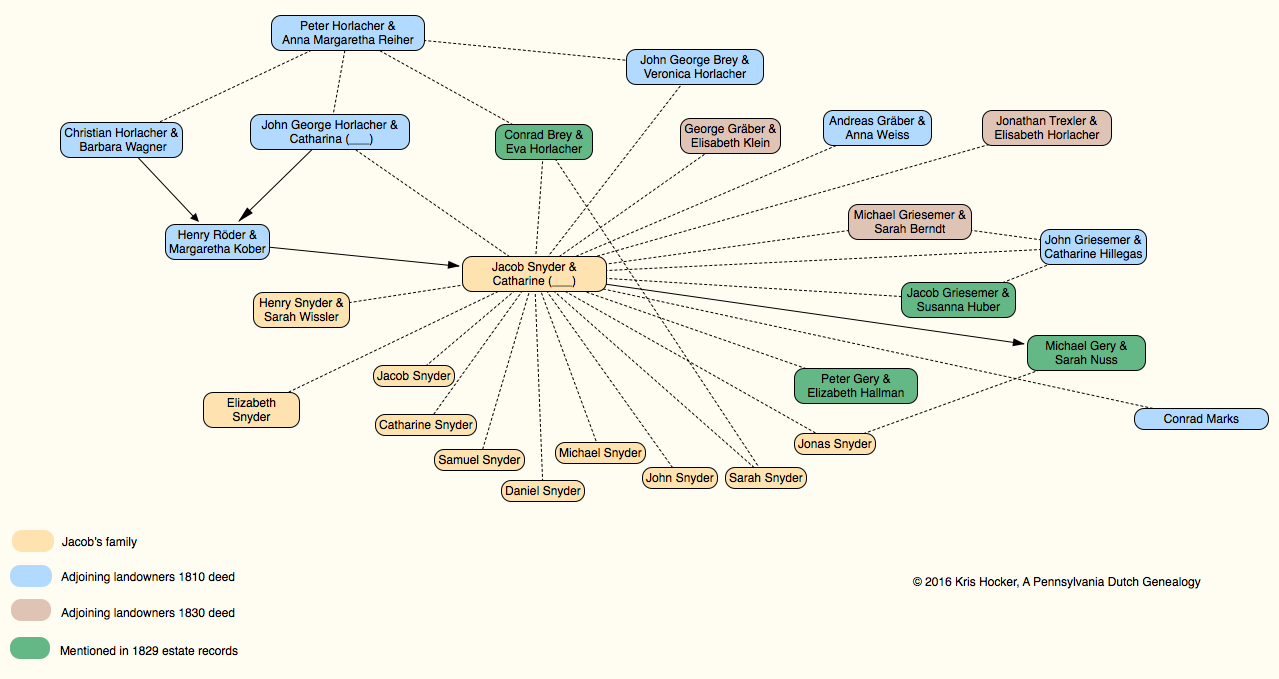

It turns out that I had already researched the Conrad Nuss family. Why? Remember Jacob Schneider’s FAN Club? There were connections between Jacob and members of the Nuss family, but I didn’t realize their importance.

Jacob Snyder’s FAN Club

Connection #1

On 2 April 1810, Jacob Schneider purchased 85 acres of land in Upper Hanover Township from Henry and Margaretha Roeder. This land adjoined that of John George Brey, John Griesemer, Andreas Gräber, Conrad Brey and Conrad Marks. Henry Roeder was the half-brother of Conrad Nuss’ wife Anna Margaretha Roeder.

If Catharina was Conrad’s daughter, then Jacob bought his land from her uncle.

Connection #2

Michael Gery was named as the guardian of Jonas Schneider in the 1829 Orphans Court records for Jacob’s estate. This Michael was one of two men: Michael Gery, son of Jacob and Gertraut (Griesemer) Gery, or his nephew Michael Treichler Gery, son of Jacob and Elizabeth (Treichler) Gery Jr. The elder Michael married Anna Maria Nuss and the younger Michael married Sarah Nuss, both women Conrad’s daughters.

Regardless of which Michael Gery the document refers to, if Catharina was a Nuss, Jonas’ guardian was his uncle.

Connection #3

After Jacob’s death, Catharina and Henry, his administrators, sold his land on 21 November 1829. To whom? Michael Gery of Hereford Township. Both uncle and nephew of this name were living in Hereford Township. I have not done enough research to determine which one made the purchase.

However, in either case, if Catharina was a Nuss, then they sold the land to her brother-in-law.

Connection #4

Conrad Nuss and family were members of the New Goshenhoppen Church. Baptisms for most of his children—including including his eldest daughter Catharine—can be found in the church records. My four times great grandfather Henry and presumably several of his siblings—Jacob, Elizabeth, and Catharina—were confirmed and/or took communion at the church. Henry and sister Catharine were both buried in the church’s graveyard. It’s not uncommon for children to be baptized in their mother’s church.

If Catharina was Conrad’s daughter, then finding her children in New Goshenhoppen Church records—even though I don’t find their father Jacob—makes a lot of sense.

Connection #5

Daniel Nuss sponsored Carl Schneider’s baptism at New Goshenhoppen Reformed Church on 21 February 1836. Carl was the son of Daniel and Sara Schneider. Jacob and Catharina had a son named Daniel.

If this is their son—and I think it possible—and Catharina was a Nuss, then her youngest brother sponsored her grandson.

Lastly, I guesstimated Catharina’s birth year at being between 1770 to 1775, based on Henry’s 1792 date of birth. I lean toward 1770 in the estimate. Conrad Nuss’ daughter Catharina was born in May 1770. This fits the family timeline and the picture that’s emerging from all the various pieces of evidence.

Conclusions

I was able to trace the ancestry of several DNA matches I share with presumed Snyder cousins back to Conrad and Maria Margaretha (Roeder) Nuss of Upper Hanover Township. My relationship to each—mostly 5th cousins—fits nicely into the 4th-6th cousin range, as estimated, with 20+ centimorgans of shared DNA.

Because Conrad’s son Johannes married Esther Schultz, daughter of Andrew Schultz and Charlotte Yeakel, my 5x great grandparents, two of these matches can not be used to prove a relationship to the Nuss family without using a chromosome browser. Which Ancestry does not have.

Fortunately, I’m also related to descendants of Elizabeth (Nuss) Hertzel, Michael Nuss, and Daniel Nuss, three of Conrad and Margaretha’s other children. This supports the idea of a familial connection between Henry Schneider and his potential grandparents Conrad and Margaretha.

Without the DNA evidence, the facts found in the paper trail did not connect for me. I knew they were meaningful, but I did not know exactly how. Knowing the connection could be through the Nuss—not Gery, Brey or Griesemer—family and their associations helps to explain the evidence found in the documentation.

Based on this research, I’m hypothesizing that Henry’s mother, Catharina, was the eldest daughter of Conrad Nuss and Maria Margaretha Roeder.

Addendum

When I mentioned this research and the conclusions to my Mom, she said, “Oh, yes. Nuss is very common up around East Greenville. My dad told me we’re related to them.” Thanks, Mom.