From the Deed to the Wills The Ancestry of Abraham Huber (1847-1910)

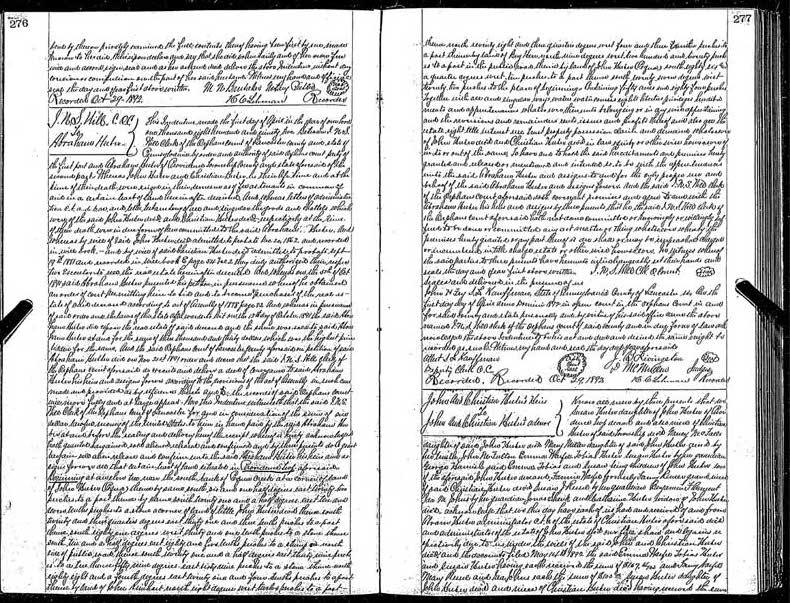

In my last post, we learned that John and Christian Huber were tenants in common on a tract of land, containing about 55 acres. Abraham Huber purchased it from the Lancaster County Orphans Court in 1892.1 After reviewing the deed that provided this information, I have three questions I want to answer:

- What are “tenants in common?”

- Why, if they both died testate, was it the Orphans Court that sold the tract to Abraham?

- What was Abraham’s relationship to the two men, if any?

Tenants in Common

As tenants in common, John and Christian Huber each owned a portion of the 55 acres. Those portions were not necessarily equal. Additionally, “tenants in common”—as opposed to “joint tenants”—did not have the right of survivorship. After one tenant’s death, the rights to their portion remained with their estate instead of reverting to the other “tenant.”

Thus, the disposition of the tract would have been determined by John and Christian’s last wills and testaments.

Orphans Court

So, if John and Christian had the right to bequeath their land as they saw fit, and both men left wills, why was it the Orphans Court that sold the land?

John Huber died 11 Dec 1862. His last will and testament was proven 20 December 1862.2 He left his “equal undivided one half of the tract of land” he held with his “brother Christian Huber” to his wife during her lifetime. After her death, he directed his executors to sell the land and pay his children their shares, after paying out his specific bequests.

Christian Huber died 8 September 1881.3 His will was proven the 19th of September. He left his share to his nephew Abraham and niece Susan, children of his brother John, along with bequests to his grand nieces, and children of nephew John. He gave Abraham 2/3 of his real estate and Susan 1/3. He instructed that none of his land could be sold until after the death of John’s widow Margaret.

Margaret died 4 February 1890.4 By that time, Christian Huber5 and Tobias Huber,6 John’s sons and executors of his will, were deceased. Abraham was named administrator of her estate.7 As per the directions in his father’s will, Abraham put the land up for sale on 21 November 1891.8 Previously, on 5 October, Abraham had been granted by the court the right to bid on the land. His bid of $3,030 was the highest. I presume that as administrator of the estate, he couldn’t write a deed to himself, thus the Orphans Court deeded the property to him.

What Was Abraham’s Relationship to John & Christian?

Both John and Christian’s wills name Abraham as John’s son. John’s will names his other children as: Christian, Tobias, John, Susanna, Ann married to James McFalls, and Mary married to John Rineer. Christian’s will also identifies Margaret McFalls, Fannie Rineer, and Mariah Rineer as his great nieces. He also leaves a bequest to nephew John’s children, but does not provide their names.

So based on three documents—a deed and two wills—we can outline the family like this:

Children of Unknown Huber:

- John Huber (children listed in order from will)

- Christian Huber

- Tobias Huber

- John Huber

- Children

- Abraham Huber

- Susanna Huber

- Ann Huber married James McFalls

- Margareta McFalls

- Mary Huber married John Rineer

- Fannie Rineer

- Mariah Rineer

- Christian Huber