I examined records from Lancaster County for Hans Georg and Anna Maria and records in Blankenloch for Georg and his three marriages. Yet, I don’t have proof regarding the identity of the immigrant. Was he the father or the son?

Internet data shows it as the father—the man who married Anna Maria Hooß. The Blankenloch ortssippenbuch states it was the son, but has no birth, marriage or death information for the father’s family after 1736.

Can the immigrant’s associations with others from Baden-Durlach tell us anything?

Hans Adam Ulrich

Hans Adam Ulrich was born in Büchig 22 February 1717, son of Hans Georg Ulrich and Anna Catharina Nagel. He married Juliana Seeger, daughter of Martin Seeger and Maria Barbara (___), on 7 September 1734. They emigrated from Büchig, arriving in Philadelphia on 12 October 1738 aboard the snow Fox. In Pennsylvania they were sponsors for Georg and Anna Maria Huber and the Hubers sponsored a number of their children, as well.

Adam Ulrich’s mother was a Nagel, just like Georg Sr.’s first wife, Anna Barbara. Anna Barbara (Nagel) Huber’s mother was an Ulrich. You’d think there would be a connection between families. With the available information, however, I was not able to find one.

However, Juliana (Seeger) Ulrich’s sister, Maria Barbara, married Anna Barbara (Nagel) Huber’s brother Hans Noa Nagel in 1722. So, there was a connection there. Adam Ulrich’s brother-in-law was also Hans Georg Huber Sr.’s brother-in-law for a time. Anna Barbara (Nagel) Huber died in December 1722, twelve years before Adam married Juliana, but Juliana likely knew her sister’s in-laws, especially Georg Jr. who was only eight years her junior.

Sebastian Näss

Sebastian Näss (or Neeß) was a shoemaker from Rußheim, Baden-Durlach. He was born about 1683 and first married sometime before 1706 as his first child Johann Michael was born on 15 March 1706. He had seven children with his first wife before her death in 1726. He married Catharina Barbara Brecht on 29 October 1726 and had two more children. She died 5 February 1730. I found no connections between Sebastian and Georg based on the available records in the ortissippenbuchs from Rußheim and Blankenloch.

Sebastian’s eldest son Michael emigrated in 1737 and Sebastian, aged 55, followed the next year on the Friendship. Sebastian served as a sponsor for two of Georg’s children and Georg sponsored Sebastian’s youngest son, Sebastian, in 1745.

Philipp Jacob Hooß

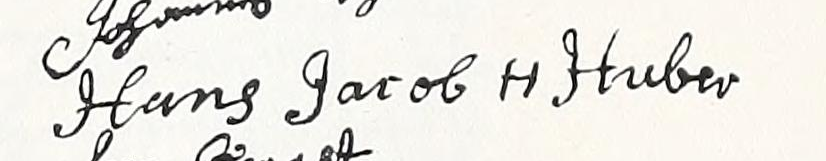

Anna Maria Hooß’s brother, Philipp, also emigrated in 1738, arriving with Hans Adam Ulrich on the snow Fox on 12 October. Philipp’s signature appears next to Adam’s on both lists B and C.

All three men—Georg Huber, Adam Ulrich and Philipp Hooß—had children baptized at Muddy Creek and the Warwick congregation. And yet, Philipp did not sponsor any of Georg and Anna Maria’s children, not even Georg’s first child born in Pennsylvania, Johann Philipp. While it’s hardly proof of anything, I do find it hard to believe that Philipp wouldn’t sponsor any of his sister’s children.

On the other hand, there is a record for “George Hover” from an Orphan’s Court on 7 March 1748/9 which states:

“JACOB HOVER an Orphan child of George Hover, chooses Philip Hofe his Guardian and he is appointed accordingly and also Guardian over all the younger children of the said George.”

The microfilm copy was a typed, “exact copy of the original” that was created in 1932, likely because the original was damaged. In old script “ss” was often written as “fs.” The typist may not have known that and interpreted as best they could. The name “Philip Hofe” may have actually been “Philip Hoss” or “Philip Hoß.”

The person appointed as guardian was most often a relative. If Philip was actually Philip Hooß, then this would indicate to me that the estate pertains to Georg Huber, the husband of Anna Maria Hooß. Jacob would have been the couple’s eldest son Johan Jacob Huber, born 4 March 1734 in Blankenloch. At 15 years of age, he would have been old enough to choose his own guardian.

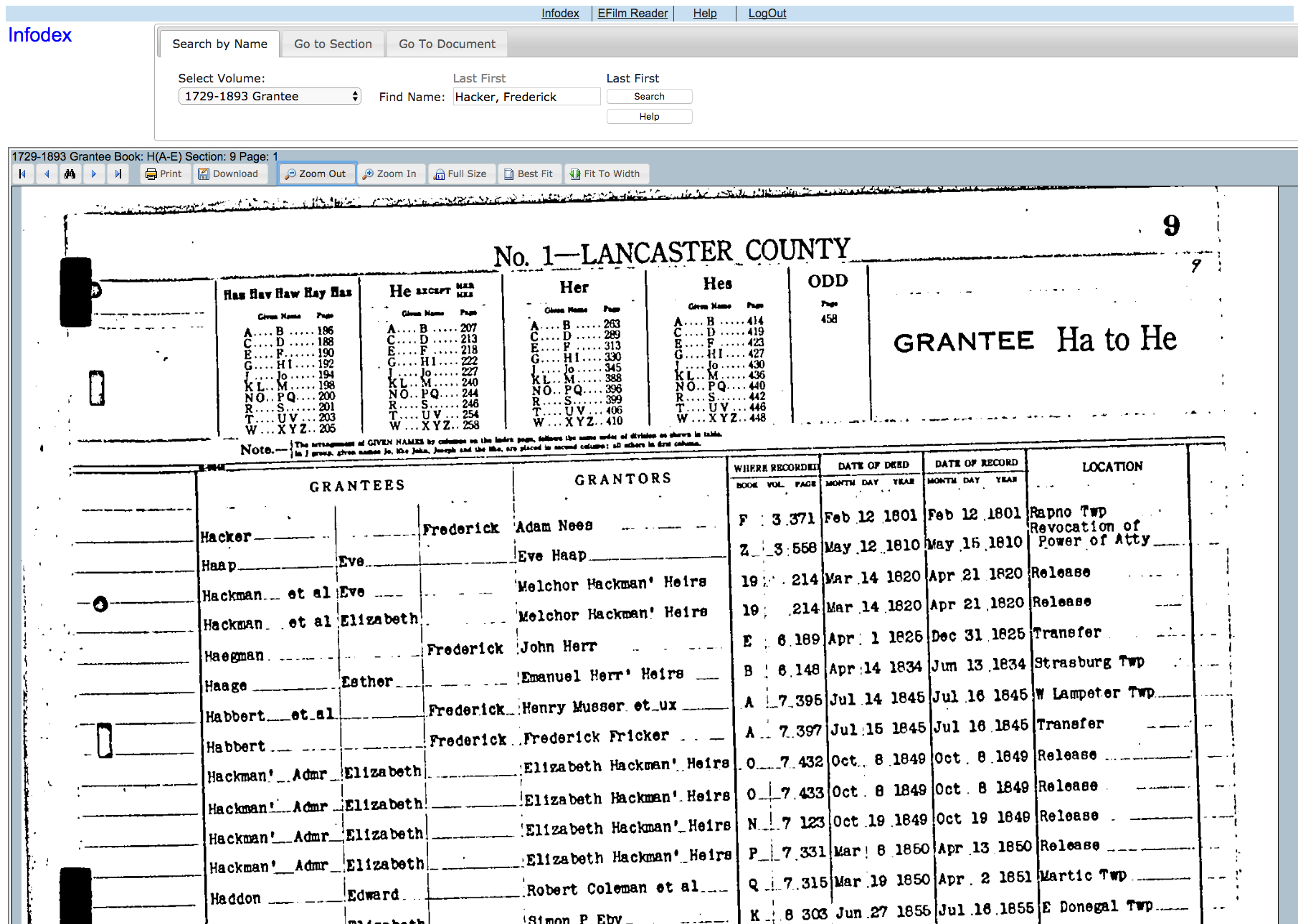

The index to Lancaster County wills indicates that Georg Huber left a last will & testament. However, it was not recorded because it was written in German. Nor does the original still exist. This unfortunate circumstance complicates research into this family.

Conclusions

In the end I didn’t find any clues regarding my ancestor Michael Huber. But since it was a long-shot, I’m not terribly surprised. It ended up being an interesting exercise anyway. I started out thinking I knew who I was researching. I found new and conflicting information that made me question that certainty. And ended up not far from where I began.

Here’s what I think.

The 1737 manumission for Hans Georg Huber, schuster, belongs to the son. I think that most likely the family emigrated in the spring of 1738. They likely travelled with Adam Ulrich’s family and Anna Maria’s brother Philipp and his wife Eva—as well as others who were leaving the Baden-Durlach area for Pennsylvania.

Georg Sr. either became friendly with Sebastian Näss on board ship—assuming they travelled on the same ship—or after arrival in Pennsylvania. They arrived about the same time, were of the same age, from the same area of Germany, had each been married several times, and were members of the same congregations.

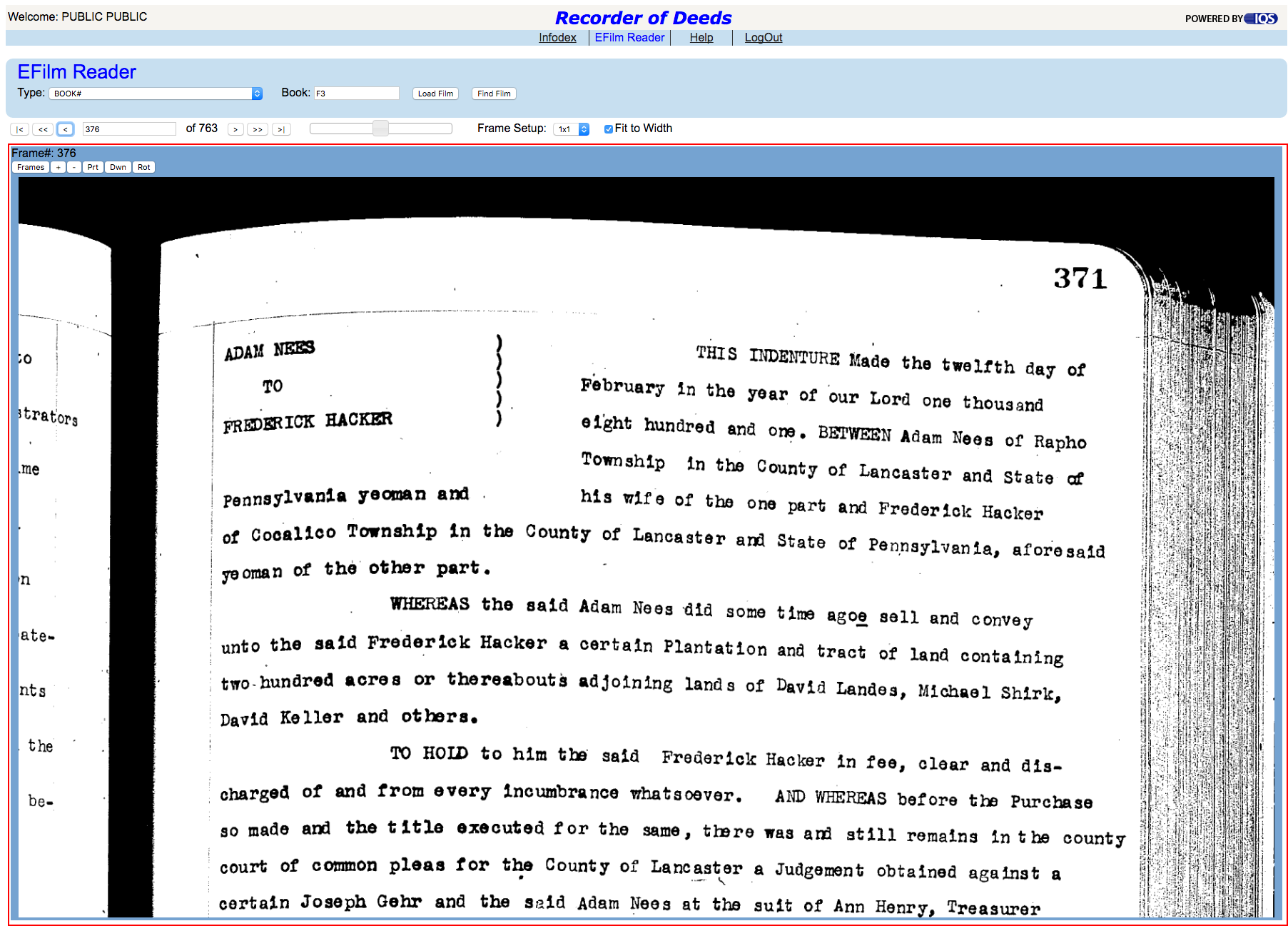

The family settled in Lancaster County—most likely in Cocalico Township—and Georg died there in early 1749. Anna Maria’s brother served as guardian for her minor children. Any of Georg’s children from his first marriage who travelled with them were of legal age by that time, possibly with families of their own.

That’s my working hypothesis anyway. It’s too bad there are no tax records for the period between his arrival and Georg’s death, nor any land records I could locate, and no will. Those could have been illuminating.

It would be interesting to look at the church records to see who the witnesses were at the children’s baptisms in Blankenloch. I wish that information had been included in the ortssippenbuchs.